India and China will avoid war but grow further apart

Tensions between India and China are at a dangerously high level following an outbreak of border violence

India-China tensions escalated significantly last week when soldiers from both sides were killed in violent confrontations on the disputed India-China border. The violence broke out despite ongoing bilateral talks to resolve a border stand-off. Delhi and Beijing are blaming each other for the crisis but also affirming their commitment to de-escalation.

What next

India and China will avoid open conflict, but they will struggle to reduce the myriad tensions between them in the long term. Since neither side will back down on its territorial claims, border confrontations could become more regular. India will reconsider some of its trade and investment protocols with China.

Subsidiary Impacts

- India will see a rise in popular movements to boycott Chinese goods.

- China will try to strengthen its relationships with India's neighbouring countries in the hope of isolating Delhi politically.

- Delhi will tighten its security relationship with Washington, Tokyo and Canberra as it tries to push back on Beijing's regional influence.

Analysis

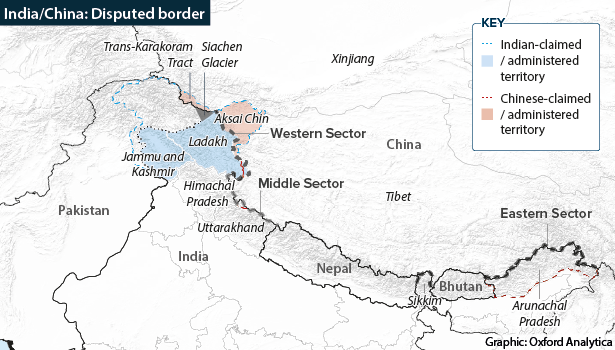

Indian and Chinese troops are frequently involved in confrontations on parts of the nearly 3,500-kilometre India-China border, which has never been formally agreed.

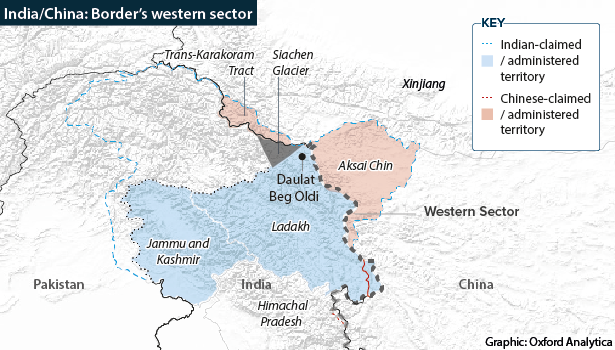

In early May, a serious stand-off developed in the border's western sector which separates Indian- and Chinese-administered parts of the disputed Kashmir region.

On June 15, violence broke out near the Galwan river (see INDIA: Border strife will intensify - June 16, 2020). Some 20 Indian soldiers were killed. China has not confirmed that it suffered fatalities, but India says it did: reports suggest there may have been more than 40 Chinese casualties.

Mistrust

India and China will defuse the current situation eventually, as neither side wants war. They will struggle, though, to ease the mistrust between them, as bilateral tensions reflect a complex entanglement of local, regional and global factors.

Local dimension

China and India will each be reluctant to take a step backwards in the western sector of their common border, which along with the eastern sector is especially contentious.

The stand-off in the Galwan valley was prompted by India's construction of a road in what Delhi insists is its side of the border. The road is meant to facilitate faster deployment of troops in the area and help protect an air base at Daulat Beg Oldi.

From China's perspective, the new road infrastructure poses a threat to its security. The Aksai Chin territory contains part of China National Highway 2019, which links the regions of Tibet and Xinjiang.

In late April, as the snows lift, China and India usually deploy forward patrols to mark out positions for the summer along the disputed frontier.

This year, India was delayed as it was preoccupied with the COVID-19 crisis. The Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) took advantage of this to advance towards the new Indian road, bringing heavy equipment to secure its new position.

The Indian army has tried to push the PLA back.

China insists the recent violence occurred because of Indian encroachment.

Regional dimension

India-China tensions have in recent years become increasingly linked to wider geopolitical dynamics in South Asia.

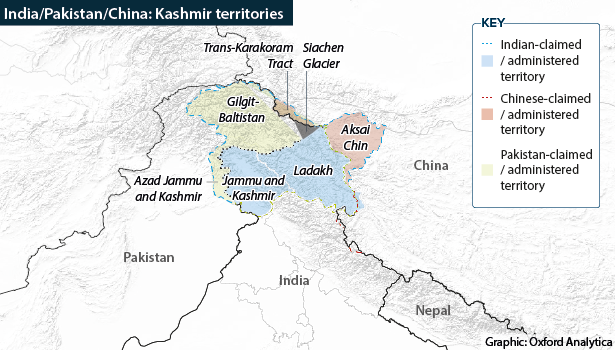

Delhi attracted strong criticism from Beijing after its August 2019 move to reorganise governance in the part of Kashmir it administers (see INDIA/PAKISTAN: Modi’s Kashmir move puts ties on brink - August 12, 2019). Delhi abrogated Jammu and Kashmir's special constitutional status and divided the state into two federally administered union territories: Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh.

India would have had no qualms about upsetting Pakistan, its main rival for sovereignty in Kashmir, but it perhaps underestimated the consequences of belittling China's claims in the region. Presenting last August's Kashmir resolution, Home Minister Amit Shah reiterated India's view that Aksai Chin is part of Ladakh.

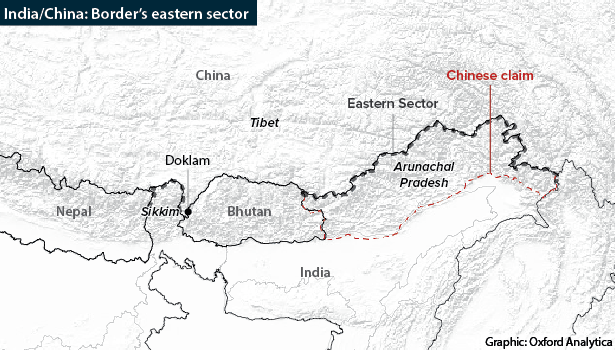

Before this year, the last serious border stand-off between China and India involved Bhutan. In 2017, they faced off for more than two months at Doklam, which abuts the eastern sector of their common border and is claimed by Bhutan and China.

India makes no claim to Doklam, but acted in support of the Royal Bhutan Army after China constructed a road in the area.

Since coming to power in 2014, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been determined to assert leadership in South Asia as part of a 'Neighbourhood First' policy (see INDIA: Regional leadership will be asserted strongly - July 8, 2019).

Meanwhile, China has tried to deepen its ties to countries such as Sri Lanka and Nepal. It has offered large investments to draw them into the Belt and Road Initiative.

Delhi believes Beijing is inciting Kathmandu in an ongoing border spat between India and Nepal.

Global dimension

Beyond their territorial disputes, China and India are struggling to build on recent undertakings to foster more accommodative relations. Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping held informal summits in Wuhan, China, in 2018 and Mamallapuram, India, in 2019. The talks were designed to allow the two leaders to understand better each other's views and priorities.

Despite the outreach, India has stepped up efforts to free itself from what it perceives as Chinese economic dominance. A recent move to introduce stricter rules for investment from bordering countries, designed to prevent "opportunistic" takeovers amid the economic fallout of the COVID-19 crisis, was almost certainly done with China in mind (see CHINA/INDIA: Chinese investment in India will fall - May 14, 2020).

Delhi has decided not to join a multi-member Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, mainly because of concerns about the dumping of cheap Chinese imports (see INDIA: Bilateralism will define regional trade policy - November 19, 2019).

There are now calls among politicians and the public in India to boycott Chinese goods, but this could be counterproductive, since India cannot realistically hurt China economically.

Delhi and Beijing will not be afraid to goad each other

China, for its part, has repeatedly blocked India's aspirations for greater influence in international institutions such as the UN Security Council.

The Modi government has taken to needling China over contentious issues such as Taiwan, albeit indirectly. After Taiwan's President Tsai Ing-wen returned to power earlier this year, two MPs from Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party attended her swearing-in ceremony.

Progress?

India and China will try to ensure their rivalry does not get out of hand, but neither will want to be viewed as an appeaser. Both Modi and Xi espouse strongly nationalist positions.

In the light of the recent border violence, there is unlikely to be a third informal summit between Xi and Modi this year.

Longer-term, there is little prospect of Delhi and Beijing settling their border differences, other than with respect to parts of the relatively uncontroversial middle sector.

Peace at the border depends on strengthening, not weakening, the ban on firearms

The two sides may simply focus on ensuring that periodic border scuffles do not escalate into the sort of violence that took place in the Galwan valley -- or worse. This will depend on strengthening the protocols that prevent their armed forces from using firearms and explosives at the border.

India has in recent days reportedly authorised its troops to open fire at the China border under exceptional circumstances, but Delhi will come under huge pressure to reverse this course. China would regard a unilateral change to the terms of border engagement as highly provocative.

Although last week's violence was by all accounts brutal, the absence of gunfire almost certainly helped keep the number of casualties down -- and avert an even deeper crisis than the one India and China currently face.