Beijing’s ambitions and assertiveness will grow

The Communist Party has gained the ability, the confidence and the need to shape the global order in its interests

China’s foreign policy is the international extension of the Communist Party elite’s overarching priority: regime security. The senior leadership seeks to defend its position within China, first and foremost by preserving and strengthening the power of the Party through which it rules. China’s growing wealth and power create new opportunities for the Party to bolster its power -- and give rise to new threats that could undermine it.

What next

Beijing aspires to be the world’s pre-eminent power, which involves gaining power, resources and prestige at others’ expense -- particularly Washington’s. If China’s ‘rise’ continues, Beijing will become increasingly open about this ambition. Nevertheless, it is keenly aware of its vulnerabilities. As long as the Party believes history is on its side and its survival is not under imminent threat, it will probably opt for patience and compromise on most issues except sensitive questions of sovereignty.

Subsidiary Impacts

- China’s ambitions centre on itself; they do not involve remaking the world in China’s image.

- China’s interests converge with other states' on climate change and economic cooperation; disputes concern how gains and costs are shared.

- China’s pursuit of its self-interest may sometimes have positive spill-overs, such as when it shares innovations, freely or otherwise.

- Despite controversies and setbacks, the Belt and Road will provide infrastructure critical for economic development globally.

- Beijing, long a practitioner of commercial espionage, is becoming bolder in its use of cyber operations to pursue its foreign policy agenda.

Analysis

China's foreign policy seeks to influence the external world in a way that burnishes the prestige, legitimacy and capabilities of the Party at home, and wards off or eliminates anything that threatens them from overseas. Such threats include military coercion, loss of access to material resources, and the circulation of ideas and information that reflect unfavourably on the Party.

Party rule does rely on repression, but owes at least as much to genuine (if poorly informed) public support for a government that most Chinese appear to view as legitimate.

The political elite's legitimacy rests on demonstrating that it is able to protect and increase the Chinese people's wellbeing, honour and national security. It does this through a combination of concrete achievements and information control.

Often there are trade-offs and the leadership seeks the optimum balance. As conditions change, so do these calculations.

Beijing generally seeks to preserve stability in world politics, because it sees this as conducive to one source of legitimacy: economic growth. However, economic growth is a means, not an end; Beijing will sacrifice this if it comes at a disproportionate cost in terms of other sources of legitimacy or regime security.

The Party sees economic growth as just one means of strengthening its power

Changing calculations

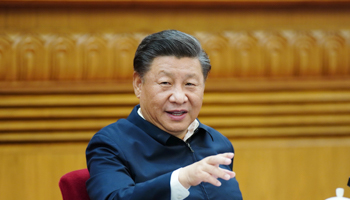

From the 1980s to the late 2000s, Beijing broadly followed a strategy summarised as 'hide our capacities and bide our time'. In 2017, Xi publicly abandoned the 'hide and bide' strategy with a public declaration that "it is time for us to take centre stage in the world".

Even as China's GDP and military spending rose to become the world's second-largest, Beijing generally avoided provocation and downplayed the potential challenge its rise represents to the US-dominated international order.

Beijing sought to exploit a window of opportunity during which it could build its strength before Washington felt threatened and moved to undermine it. Beijing's insistence that it did not intend to challenge the United States elicited suspicion, but containing China never became Washington's top priority.

Beijing's window of opportunity has now closed. Washington is moving against China. This alone would force China's strategy to change, but at least two other developments also drive change.

First, Beijing has decided it has now reached a point at which, in order for China to continue its economic development, it must shape the world in a manner conducive to this. This requires pro-active economic diplomacy.

Second, Beijing believes that China's 'comprehensive national power' has grown to the point where it has the ability to influence events beyond its borders. It has gained confidence.

China's foreign policy became more assertive following the 2008 global financial crisis, and then even more so under President Xi Jinping's leadership from 2012 onwards.

Donald Trump's election as president, in Beijing's view, marked the next stage in the United States' long decline, dealing a blow to US prestige, undermining faith in the reliability of Washington's international commitments and leaving a leadership vacuum at the heart of international institutions (see CHINA: Beijing prepares to seize gains from Trump win - November 14, 2016).

The difficulty Western countries have faced in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic has boosted China's confidence further (see CHINA: COVID-19 gives China a diplomatic opportunity - March 31, 2020).

Beijing reflects too much on Washington's mistakes to treat the United States as a model of how China should behave as a superpower, but in some ways it is following in US footsteps.

It is trying to build a regional sphere of influence, strengthen economic relations with strategically important countries, develop a military with a global reach and establish new international institutions that are more open to Beijing's influence and better serve its interests.

It is also investing in 'badges' of superpower status, such as aircraft carriers and human spaceflight (see CHINA: Aircraft carriers will extend Beijing’s reach - January 23, 2020 and see CHINA: Space station will pay political dividend - September 27, 2019).

Rise of the diplomats

The profile of foreign policy within the Chinese political system has risen. It is a higher priority and receives more attention at top levels (see CHINA: Foreign policy will rise up Beijing's agenda - January 25, 2018).

In 2017-18 the foreign policy apparatus was restructured (see CHINA: State restructuring will have enduring impact - March 23, 2018). Yang Jiechi became the first diplomat in a decade to gain a seat on the Politburo.

Hawkish public statements by Chinese officials are not new, but up until recently they have not generally come from diplomats.

Diplomats now feel emboldened to speak out on sensitive issues

The Foreign Ministry was traditionally viewed as relatively dovish and a frequent target of nationalist ire online, but it has an incentive to stir a 'manageable' amount of trouble internationally, because this generates a demand for diplomacy that it can supply.

Divisions among Chinese policymakers relate to strategy and tactics rather than basic beliefs or objectives.

Hawks in favour of assertive tactics are probably a majority; a minority favour resuming a more patient approach, believing that China cannot yet afford confrontation.

One element still weighing in favour of more patient foreign policy is the Party's Marxist heritage. Although Marxism has lost its power as a source of regime legitimacy, Chinese policymakers remain heavily influenced by certain Marxist assumptions about the world.

In particular, they believe economic arrangements ultimately determine political ones. This is one reason why Chinese diplomacy focuses foremost on economic matters. The Belt and Road Initiative aims to further China's immediate economic and geopolitical interests, but also aim to reshape the world economy in a way that will naturally shape world politics to Beijing's advantage over time.

Interests, not values

Interests drive Chinese foreign policy. Propaganda slogans notwithstanding, values play a negligible role except as rhetorical and ideological resources Beijing sometimes uses to promote its interests.

When China cooperates, it is on the basis of shared material interests

Yet, in a way, interests-driven foreign policy expresses core beliefs and values. The world-views of Chinese policymakers are shaped by a society that for decades has been characterised by:

- low trust, weak and corrupt institutions, lip service to ideals, scarcity and cut-throat competition; and

- pervasive propaganda promoting a heavily curated version of history in which China is repeatedly a victim of foreign violence, exploitation and humiliation.

Growing up and thriving in this environment instils basic assumptions about human motives and behaviour that give Chinese policymakers a social Darwinist view of the world.

For Beijing, pursuit of international peace and stability is expedient and tactical more than it is driven by a sense that these are inherently desirable or a deeper belief in their moral value.

Beijing frequently invokes and affirms the norm of national sovereignty, but this is contingent on it benefiting the Party. In practice it is already jettisoned selectively, and this could become more common as China's ability to violate the sovereignty of other states increases and the price it pays for doing so falls.

Nationalism

Xenophobic and chauvinistic nationalism is a potent force in Chinese politics. The Party leadership encourages and probably subscribes to it. Hostility towards the United States and hatred of Japan are considered normal, albeit often combined with grudging respect.

The Party ascribes the 1989 Tiananmen democracy protests to excessive affinity for the West. Since then it has invested heavily in 'patriotic education' with several goals:

- to make public opinion hostile to the West and reduce the appeal of liberal values;

- to fill the ideological vacuum left by the loss of faith in communism by recasting the Party as a nationalist liberation movement against the Japanese empire;

- to cast China's lag behind the developed world as the result of foreign imperialism rather than Mao's disastrous economic policies; and

- to reinforce the idea that authoritarianism is necessary because history shows that without 'unity' under a strong government, China falls into chaos and is then exploited by foreigners.

Members of the current political establishment no doubt share the nationalist views they promote among the public, but the influence of these views can be overestimated. Nationalist language provides politically acceptable 'cover' for other agendas.

However, as cohorts raised on patriotic education assume positions of power, the disposition of policymakers is likely to become even more nationalistic. More of them will have a middle-class upbringing and have 'post-materialist' values that give idealistic nationalist goals greater priority.

The present leadership understands that nationalism is a double-edged sword.

It can inoculate the public against sympathy with liberal democratic ideas, divert public discontent and rally the public around the flag.

However, nationalism works against the Party if citizens believe Beijing's foreign policy falls short of the nationalistic values it proclaims. A tiny percentage of China's huge population is enough to cause havoc if it becomes politically mobilised behind a particular demand -- something social media makes easier.

Sometimes the leadership deliberately stirs up nationalist activism; at other times activism appears to be spontaneous and can become unduly disruptive. So far Beijing has always managed to rein it in. Whether it can continue to will depend on its crisis-management ability.

Public opinion probably does influence Chinese policy. Nationalist protests, or fear of them, can force Beijing to do things it would prefer not to.

This may become more common as China's economy slows, particularly if the COVID-19 pandemic initiates a period of long-term stagnation.

If the leadership can no longer derive legitimacy from rising living standards, it will probably resort more to nationalism as a long-term legitimating ideology and short-term lightning rod.

China's self-image

Useful generalisations can be made about how Chinese view their country and its place in the world.

Chinese view their country as unique in its antiquity, cultural richness and peaceful disposition.

Many Chinese appear convinced that their country requires unique political arrangements. In particular, its huge and unruly population require authoritarian rule to prevent collapse into violent chaos. This idea suits the interests of the present ruling elite, and they promote it, but it is probably also a consequence of personal experience of lawlessness during the Cultural Revolution. As the Cultural Revolution cohorts dwindle, scepticism may increase.

Chinese believe that for most of human history their country was the richest, most powerful and most culturally and technologically advanced in the world. This is its natural position, which in time China will resume. No other country besides the United States can plausibly aspire to global pre-eminence; many Chinese take theirs for granted.

Chinese view their country as exceptional

In the Chinese view, China fell from pre-eminence in the 19th and early 20th centuries because of Western and Japanese imperialism. The history of this period is well-known in China and resentment over it is genuine; the government cultivates it but does not need to manufacture it.

Historical grudges explain the seeming oversensitivity that Chinese often display towards slights that appear trivial or simply imagined to Westerners, whose knowledge of Chinese history is often negligible.

Beijing exploits this resentment and readily exaggerates the degree to which particular actions 'hurt the feelings of the Chinese people'.

The shame of the 'century of humiliation' is yet to be erased, and in the eyes of many Chinese probably never will be until:

- China is again the richest, most powerful and most respected country in the world;

- China reincorporates territories 'lost' to foreign imperialism, most importantly Taiwan;

- foreign governments and citizens are too frightened to express views Chinese find offensive; and

- erstwhile imperialists, most importantly Japan, apologise abjectly and frequently for past aggression.

This is the vision of a 'perfect world' that many, if not most, Chinese would like to see realised eventually, though it is a low priority compared to bread-and-butter issues and daily irritants such as corruption and censorship. There is also a sense that China can afford to be patient because history is on its side.

China's foreign policy elite probably share these basic views and ambitions, but are less inclined to take China's continued rise for granted. They are more sensitive to China's vulnerabilities:

- economic weaknesses related to debt, demographic ageing and the middle-income trap;

- military weakness relative to the United States;

- strategic vulnerabilities arising from reliance on maritime trade and imported natural resources;

- China's lack of soft power;

- the threat of information that damages the Party's image spreading within China;

- the threat of liberal democratic ideas gaining support within China (see CHINA/US: Ideological conflict will intensify - May 18, 2020); and

- the threat of domestic nationalism turning against the Party.

Beijing tries to work within the constraints these weaknesses impose, to mitigate the dangers they create.