Tension on China’s inland frontier may grow over time

Beijing’s rising power is changing its relations with its inland neighbours

China has largely achieved its objectives in Central Asia, where it is now the dominant economic power. Moscow is a key partner in opposing Western hegemony, but Pakistan is the closest thing China has to an ally and depends increasingly on Chinese support. Territorial and economic conflicts with India are pushing Delhi closer to Washington and Tokyo.

What next

No formal China-Russia alliance is envisaged, and relations may become more uncomfortable as the power imbalance grows, putting Central Asian governments under pressure. India will not threaten China economically for decades, but could well rise as a security threat if its military capabilities and, particularly, partnerships strengthen. The cost of Chinese aid to Pakistan will probably rise; the risk of nuclear proliferation weighs heavily against Beijing allowing the state to collapse or fragment.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Russia would probably oppose any attempt to increase China’s overt military presence in Central Asia.

- Despite the return home of militants from Islamic State territories in Syria and Iraq, the threat from radical Islamism remains low.

- Divergences of interest will not prevent China-Russia cooperation for now, but Beijing cannot rely on Moscow to defer to its wishes.

Analysis

China's western frontier is remote from its urban and industrial heartland, but crucial to its geoeconomic policy and future prospects.

Central Asia

China's economic goals for Central Asia are:

- establishing Central Asia as a transit region for trade with Europe and the Middle East;

- exporting manufactured goods to the region, and creating new markets for them there; and

- importing energy from the region.

China is the key economic partner for the Central Asian republics, accounting for roughly 20% of their exports and nearly 40% of their imports. Cargo transit has increased dramatically since 2015. China is one of Central Asia's largest consumers of hydrocarbons. In 2019, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan supplied 15% of China's natural gas, and China accounted for almost all of Turkmenistan's exports.

China had reportedly invested almost USD140bn in Central Asia as of last year. It has built new roads, pipelines, power stations, factories and trade infrastructure.

Numerous projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) have been completed, including major ones such as the Moynak hydropower dam in Kazakhstan. However, the level of nonperforming assets is high, and many projects fail or are chronically delayed.

Within the region, only Kazakhstan's GDP has grown significantly faster since the BRI's launch in 2013.

Central Asian governments worry about excessive economic reliance on China and possible 'debt traps', particularly in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (see CENTRAL ASIA: Silk Road poses debt risk alongside wins - April 10, 2018). Both have debts to China exceeding 20% of GDP. Kyrgyzstan asked for debt relief in April.

Security

The BRI is primarily an economic project, but China sees economic prosperity as key to achieving long-term political stability in Central Asia. This is important for China's security because Central Asia borders Xinjiang and is a buffer between China and Afghanistan, as well as a potential source of terrorist and extremist threats. There are perennial fears that the region will collapse into instability, though it remains relatively stable, even amid Uzbekistan's and Kazakhstan's recent power transitions.

Chinese regional security cooperation focuses on the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). It provides military equipment and training and holds joint exercises. A small Chinese paramilitary presence has been established in Tajikistan since at least 2016. China's People's Armed Police has an unofficial base in Tajikistan's Badakhshan region to monitor activity across the border in Afghanistan.

China shows little interest in replacing Russia as Central Asia's pre-eminent security partner, but its involvement is increasing. If this continues, eventually it might create friction with Russia, which will have less and less to offer the region.

The Central Asian states will continue to value good relations with Moscow. Their foreign policy has long centred on balancing competing powers in order to avoid domination by any one.

Public relations problem

China is trying to build its soft power, primarily through educational programmes. It has set up Confucius Institutes, and tens of thousands of Central Asian students have studied in China, many on scholarships.

Nevertheless, public opinion is generally hostile. Perceived economic domination along with employment of Chinese nationals and limited job creation for locals have sparked anger.

Anti-China protests are relatively common, particularly in Kazakhstan. In September 2019, a wave of protests saw several hundred people arrested. The protests were originally about alleged plans to build Chinese factories, but quickly accumulated related demands concerning other aspects of Chinese economic activity and perceived job losses to Chinese immigrants.

Public anger has rarely prompted government action but has occasionally caused the cancellation of projects or initiatives, including a logistics centre in Kyrgyzstan in February.

The internment of people from ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, including ethnic Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, has exacerbated anti-China sentiment. The issue is widely known in Central Asia, though the attention is mostly on co-ethnics rather than the Uighurs, who account for the great majority of those detained. However, Central Asian governments have not confronted China about the detentions (see CHINA: Muslim states will turn a blind eye to Xinjiang - April 15, 2019).

Pandemic impact

Central Asia's economies now confront a triple shock from the COVID-19 pandemic: the economic consequences of lockdowns, a collapse of earnings from remittances and falling commodity prices.

The pandemic will increase China's importance to Central Asia

The region's governments need outside support to tackle the virus and return their economies to health. Only China has both the economic strength and the interest in providing it.

The pandemic will hit the BRI hard in the short term. China's government estimates that 50-60% of projects have been affected. Activity will resume after the pandemic, though the new economic conditions are likely to lead both China and its Central Asian partners to rethink the viability of large projects.

Russia

Russia and China, especially since 2014, have developed a pragmatic entente based on shared interests, poor relations with the West and a willingness to compromise on bilateral disagreements.

Geopolitics

Beijing sees Moscow as a partner in opposing US hegemony, particularly US democracy-promotion and deployment of missile defence systems. Each has supported the other, passively or actively, on controversial issues such as Russia's annexation of Crimea and China's authoritarian policies in Hong Kong.

Military cooperation, including joint exercises, is a pillar of the relationship. Naval exercises have been held in the Baltic and South China Sea. The two are the leading powers in the SCO and have engaged Iran in trilateral exercises. Military cooperation builds and demonstrates trust and signals joint opposition to Washington, though no formal alliance is envisaged.

Russian arms sales to China have expanded since 2010. Russia now makes its best technology available to China, including the development of a missile attack early warning system. Russia has also sold China Su-35 fighter jets, one of its most advanced conventional weapons. It had been due to sell an S-400 anti-aircraft missile system to China, though the sale was delayed due to the pandemic and is now 'suspended'.

China's energy imports from Russia have also increased. Its oil imports have risen 60% since 2015.

China does not need active Russian engagement in the BRI, but it does need acquiescence, since its routes pass through the Russian-dominated Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), whose Central Asian members are Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

Beijing has promoted cooperation between the EEU and the BRI, which are potentially complementary: the EEU reduces trade barriers within the bloc while the BRI develops physical infrastructure to facilitate trade. However, efforts to link the two directly have foundered because Russia and the Central Asian members resist the idea of a free trade area with China.

China is now by far the largest trade partner and investor for Central Asia. The EEU is important politically but has done little to boost trade. Moscow has accepted a 'division of labour', in which China is the primary economic player and Russia is the primary security player. Moscow is the de facto leader of the regional Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). It has bases in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, and the Russian Aerospace Forces have their main spaceport in Kazakhstan. China is not a member.

Friction

Russia has close relations with India and Vietnam and sells them advanced military equipment that could be used in a potential war with China over disputed territory or waters. Russia supports India's bid for a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, which China opposes, and has conducted offshore drilling with Vietnam in waters claimed by China in the South China Sea (see CHINA: Military moves may precede maritime escalation - June 25, 2018).

Russia's and China's interests clash in various areas

China's interest in Arctic resources and sea routes could come into conflict with Russian territorial claims (see INTERNATIONAL: Polar Silk Road will alter geopolitics - September 18, 2018). The two governments are cooperating on resource extraction, but their long-term interests diverge. Russia objects to China's challenging the privileged position of the Arctic states and China objects to Russia's expansive interpretation of its rights and authority over the northern sea route. In June, criminal charges were brought against the president of the Russian Arctic Academy for spying for China.

The two countries' deep-rooted and long-term interests in cooperation will be tested as the imbalance between them grows. Increasingly, Russia is the junior partner, which runs counter to Moscow's perception of itself.

The relationship could become antagonistic if China becomes less considerate of Russia's interests in its near abroad and makes moves that would undermine Russian-led organisations, for example, seeking bilateral trade deals with EEU member states, or military bases on CSTO territory.

In the long term, it is possible that Russia might reduce or end its current cooperation with China, and instead try to repair relations with the West and cooperate more closely with India.

Cracks opened at the start of the coronavirus pandemic, but have been quickly mended. In June, the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov declined to attend a BRI conference, raising the possibility that Moscow was turning against the initiative. However, in the short term, Moscow cannot risk losing Beijing's support while Russia is isolated from the West and its economy struggles.

India

China-India relations are at a critical moment of strain

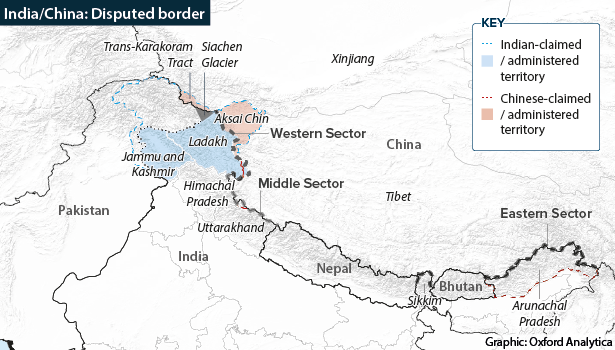

China and India have never agreed a border. They fought a one-month war in the Himalayas in 1962, in which China came out on top. After that, bilateral relations remained tense, but India did not press territorial claims, in de facto recognition of China's military superiority.

This has changed over the last 20 years with India's rapid economic growth and the rise of Hindu nationalist ideology.

Long-established informal arrangements in remote and poorly monitored parts of the Himalayas are now breaking down. Tensions have mounted since a 2017 stand-off at one of the China-India-Bhutan tripoints abutting the 'eastern sector' of the de facto border. They spiked in June this year with violent confrontations between Chinese and Indian soldiers in the 'western sector'.

The face-off with India is a far lower priority for Beijing than challenges on China's maritime frontier, but the two are no longer entirely separate, because fear of China is prompting Delhi to cooperate more with Beijing's two major strategic rivals, Tokyo and Washington.

The United States sells weapons to India and participates along with India and Japan in the annual 'Malabar' naval exercises.

Japan is a major investor in India, especially in infrastructure. The relationship is a high priority for Tokyo, which sees India as having high potential as a market and as a security partner in balancing China's growing power.

Together with Australia, the four countries form the 'Quad', an informal group of democratic states that are concerned about China and cooperate in security affairs. India's preference for 'strategic autonomy' and wish to avoid antagonising Russia -- its major arms supplier -- means they are unlikely to form an alliance (see INDIA: Delhi is not yet ready for alliances - August 21, 2020). However, Delhi is under increasing pressure from Washington to commit more strongly to the Quad. This could erode ties with Russia over time.

Although Delhi sees Beijing as its main geopolitical rival, China does not regard India as a significant threat. Its main interest in India is as a market, but the economic relationship is highly unbalanced.

Indian tariffs began cutting into China's surpluses even before the most recent geopolitical confrontation. In response to this year's violence on the frontier, Delhi has blocked imports of Chinese goods in some sectors and encouraged consumer boycotts in others. It has threatened more far-reaching trade boycotts and investment embargoes, though even if it follows through, some trade is likely to gravitate back to China for want of alternatives (see CHINA/INDIA: Chinese business in India may be set back - July 27, 2020).

In the long term, Delhi's industrial policy explicitly aspires to position India as a technological, manufacturing and investment alternative to China in the hope that Indian firms will eventually displace Chinese firms from domestic and global markets. That is not a realistic prospect in the foreseeable future and probably not for decades. India still depends on Chinese technology and investment in so many critical areas that excluding them would damage India's own economic prospects.

Pakistan

Pakistan helps China put pressure on India and secure its borders against Islamist violence. It even shows signs of deferring to Beijing in the context of China-US strains. Military cooperation has tightened in the last few years, with weapons sales, joint exercises and joint border patrols.

The 'China-Pakistan Economic Corridor' (CPEC), the most expensive part of the BRI, connects inland China to infrastructure and energy investments stretching to the Gulf.

Yet the partnership is uncomfortable. The Pakistani state is unstable, challenged by separatist and Islamist militant groups. Parts of the military operate private franchises beyond the civilian government's control. Private franchises play an ever-larger role in running major infrastructure and investment projects, and China has problems controlling them, leading to delays and cost overruns.

Chinese infrastructure and other investment projects have not delivered the rapid structural transformation envisaged. China plays an increasing role in supporting Pakistan's economy. It holds at least one-fifth of Pakistan's public debt and even more is probably owed to private Chinese contractors.

Chinese aid helps keep the Pakistani state intact.