China will use foreign aid for strategic aims

A new international development cooperation paper released last month signals a shift in China’s approach to foreign aid

China has for the first time released an international development cooperation policy. It consolidates and formalises a shift that has been underway, using examples of recent practice to present China’s new approach. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is presented as a key part of China’s development policy, alongside the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

What next

The policy will direct China’s experience and resources towards realising the SDGs. At the same time, Beijing will use development policy to promote approaches to economic integration, trade and technology standards that help create a world where the Chinese state and Chinese businesses have more influence and power, and China is not challenged on ‘core interests’ such as Hong Kong, Taiwan, Xinjiang and the South China Sea.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Trilateral cooperation with developed country aid donors is affirmed, but China is unlikely to contribute money.

- A new interest in cooperating on ‘governance’ suggests a willingness to support authoritarianism overseas.

- The distinctions between aid, economic diplomacy and geostrategic competition will remain blurred, and may become more so.

Analysis

China has for the first time released an international development cooperation policy -- officially titled in English 'China's International Development Cooperation in the New Era.'

Why now

China has run development projects overseas for decades. The document puts its spending on development aid at CNY270bn (USD41bn) between 2013 and 2018, split almost equally between grants and concessional loans.

Until 2018, overseas development projects were managed by the Ministry of Commerce, and sometimes other ministries and agencies. As this activity grew in the 2000s and 2010s, it became increasingly evident that Chinese aid was sometimes incoherent and not necessarily effective.

Policymakers were persuaded that as overseas engagement stepped up, better institutional arrangements were needed. In 2018, the China International Development Cooperation Agency was created to provide this (see CHINA: State restructuring will have enduring impact - March 23, 2018).

The new development cooperation policy is the next step, probably as the result of several factors:

- Over time, Chinese professionals and bureaucrats have been exposed to Western development discourse and have made the case internally for some version of it.

- Chinese officials may have taken notice of more recent 'aid scepticism' discourse in the West, and seen an opportunity to show China as a responsible global power in contrast.

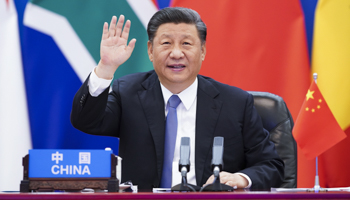

- All this comes just as China under President Xi Jinping pushes for a leading role on the global stage.

New emphasis

The new policy document indicates that China now aims to support countries to identify and follow appropriate development paths, rather than simply provide aid. Healthcare provides an example of the distinction: foreign aid might involve funding construction of hospitals or sending teams of doctors (as China did for years) whereas a development approach would look more broadly at health needs and desired outcomes and develop a strategy to achieve them, including priorities for funding and institutional changes.

Chinese aid has traditionally focused on infrastructure investments through concessional loans, alongside construction of hospitals and postings of Chinese medical teams, the establishment of agricultural technology demonstration centres, and provision of scholarships and training of foreign personnel in China.

These activities will continue, but China now sees them as part of strategic development cooperation, which includes advising countries on better policies and planning to reduce poverty and achieve economic growth. In Cambodia, for example, Chinese development officials have helped to develop a plan for agricultural modernisation.

A chapter titled 'Enhancing the endogenous growth of developing countries' states that "Guided by the conviction that 'it is more helpful to teach people how to fish than to just give them fish', China aims to help developing countries to enhance their capacity for independent development".

This attempts to address a criticism that Chinese contractors simply build things and then leave. China is now shifting to a longer management presence and more general support for development planning, although this is not yet done widely.

Governance

"China has helped other developing countries increase their governance capacity," the document says, "by assisting with their national planning, sharing its governance experience with them".

An Institute of South-South Cooperation and Development was set up by China in 2016 and hosted at Beijing University with the goal being to share "China's experience in state governance and train talent from other developing countries to modernise their governance capacity".

This emphasis on governance is presented in a technical and administrative sense -- supporting effective planning for the economy and different sectors. China has expertise and experience in many areas that is valuable and relevant to developing countries.

However, governance also involves law, regulation, policy and politics. China traditionally steered away from these on the basis of non-interference in the internal affairs of other states. However, it is now willing to make the case explicitly for the benefits of aspects of its authoritarian governance model to development partners.

This will worry many in both developing and developed countries, given China's approaches to media and internet censorship, restrictions on civil society, repressive uses of big data, use of surveillance and denial of civil and political rights.

Chinese assistance with governance might now extend to sharing techniques on how to be more effectively authoritarian and supplying the relevant equipment, for instance surveillance technology (see CHINA: China will lead the world in smart cities - March 26, 2019).

China is not as wary as it once was of politically sensitive issues

South-South aid

The UN 2030 SDGs are presented as a key part of China's development policy (see PROSPECTS 2021: SDGs outlook - November 13, 2020). Beijing wants to show that it sees its development cooperation as being in the context of multilateralism -- and that it is more closely aligned with the agenda of the Global South, which shaped the SDGs, than with donor organisations such as the OECD's Development Assistance Committee.

China describes itself in the document as a "major" country but also a developing country. This means that its assistance is framed as 'South-South cooperation' and therefore categorically different to aid provided by OECD states.

China's claim to be a developing country elicits scepticism in developed and developing countries alike on account of its enormous aggregate wealth and advanced technology. However, the UN Human Development Index does still classify it as 'developing' based on life expectancy, average years of schooling and GDP per capita, while the World Bank classifies it as 'middle income' and therefore still entitled to development funding.

China's call for Northern donors to meet their obligations as developed countries "fully and in time" may resonate with other developing countries.

Beijing may also be taking aim at recent reconsideration in developed countries of international commitments and appropriate levels of development spending. For instance, the United Kingdom recently abandoned the target of allocating 0.7% of GDP to overseas development assistance.

China wants developed countries to transfer more wealth to developing countries

China's new policy does not adopt any of the OECD Development Assistance Committee language on aid effectiveness -- the benchmark for best practice for traditional aid donors. Chinese aid has been criticised as opaque in its methods and funding, and it does not publish evaluations of impacts and effectiveness.

The new policy claims that there will be independent monitoring and evaluation of interventions. However, it is not clear who will carry these out and whether they will be available for others to learn from. It seems likely that China would only accept monitoring and evaluation by institutions that can be relied upon not to be publicly critical.

Geographical reach

The policy sets out the range of countries and sectors where China has provided cooperation to date. Unlike those of OECD donors, it gives no geographical or thematic prioritisation, and no budget allocations are given for countries, which does not help countries or other donors to plan.

While the policy document provides some data on funding in the past, and some individual commitments -- for example, a USD2bn COVID-19 assistance fund -- it gives no overall budget for development spending, much less a precise allocation for countries or sectors.

China appears to want to work in all major development sectors, and in a far wider range of countries than would be considered by traditional donors. This reflects its size and resources, and a desire to be as widely engaged as possible, even if this entails some trade-offs in terms of depth of engagement and manageability.

The geographical scope of China's overseas development plans is unusually wide

Nevertheless, certain countries do appear frequently in the lists of initiatives. They include:

- near neighbours Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Nepal, Bangladesh and Pakistan;

- key BRI partners Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan; and

- key African partners Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe and Zambia (see CHINA: Africa forms part of Beijing’s development plan - November 2, 2020).

All of these countries are economically or strategically important for China in some way.

Many small countries are also mentioned, such as Timor Leste and Sao Tome and Principe. These relationships can be valuable in international fora where states participate on a one-country-one-vote basis, for example, the UN Human Rights Council or the World Health Assembly (where there has been a push to restore observer status for Taiwan).

Belt and Road

The new policy strongly links China's development cooperation with promotion of the BRI. It advocates "building platforms for the Belt and Road Initiative to dovetail with the development strategies of participating countries", including through "infrastructure connectivity [...] equipment standardisation, trade facilitation, and technological standardisation".

This positions the BRI and development cooperation policy as ways to advance China's ambitions to set global norms and standards, which Beijing sees as critical to China's economic future and which feature prominently in policy discussions of decoupling and control of the core technologies that will drive future economic growth (see CHINA: Beijing seeks to lead global standards-setting - December 30, 2020).

Trilateral cooperation

The policy endorses trilateral cooperation with developed country donors. Some, such as the Australia, Germany, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, have participated in trilateral cooperation projects with China before. For example, there have been UK-funded projects with China in agriculture, global health and disaster management. The agriculture trilateral had a GBP10mn (USD13.7mn) budget and ended in 2017. Trilateral projects have had mixed success. The merits of pursuing further rounds are debated in Western aid agencies.

China has to date not contributed funds to trilateral projects, on the grounds that its aid is South-South cooperation and in pooled aid projects some funds might be spent in the North on management or technical inputs, which would be an inappropriate South-North transfer.

Instead, China provides technical expertise, approval to use technologies and manpower, including government staff. Official endorsement by the national government can get bureaucratic processes in China moving and get useful people and companies to participate. China might cover the cost of some activities in China, but would not fund activities in the target country or contribute to project management costs. Fees might even be charged for some of the Chinese expertise, depending what can be negotiated.

Given the size of China's economy it is now difficult for Beijing to insist that the traditional donor be the sole provider of funds. However, there is no indication that China will commit its own resources alongside those of developed country partners, officially because it still views itself as a developing country but also, in fact, because it would dislike not having complete control over how its funds were spent.

Developed country partners will have to decide whether funding projects involving China is justified in terms of delivering effective aid or perhaps other benefits.

It is not clear whether China's approaches to trilateral cooperation will go beyond standalone projects to policy dialogue and a governance agenda, in line with the wider reorientation of its development cooperation. Developed countries might welcome a transparent discussion on these issues, but on past form China will prefer a bilateral approach.

China will prefer to keep its development cooperation bilateral

There is no evidence yet that China is willing to join donor coordination groups in developing countries. It still prefers to engage in direct bilateral dialogue with governments. This is unlikely to change in the short term even if China puts more development staff into developing countries.

However, developed-country governments could still find ways to interact with Chinese officials in-country to build understanding and achieve better coordination. Developed-country donors can also encourage developing countries to bring all donors in the country together to look for synergies and links between their development cooperation endeavours.