New defensive strategy allows Syria regime to fight on

Following a series of recent defeats, the regime is scaling back its ambitions to reconquer rebel areas

Rebel forces captured the north western city of Jisr al-Shughur on April 25, a strategic gateway connecting north-west Syria to the regime's coastal heartland. The loss is the most significant defeat suffered by the regime in recent months, following the fall of the provincial capital, Idlib, in late March and Nasib, the last regime-held crossing point with Jordan, in early April. Loyalist troops have not suffered such a succession of major defeats since the initial wave of rebel advances between late 2012 and early 2013. The recent losses are partly the result of an influx of logistical support to the rebels from their state supporters, but also reflect the worsening of the regime's long-standing shortage of manpower, which is its main vulnerability.

What next

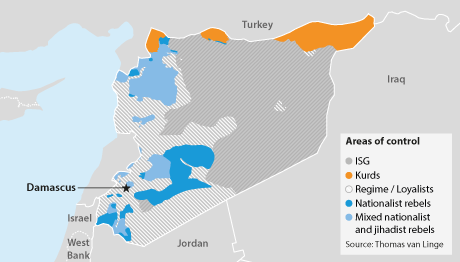

The latest setbacks do not signal an imminent collapse of pro-Assad forces. However, they do mark the end of the regime's counter-offensive operations aimed at recapturing territory from the rebels in the north and south of Syria. The new phase will see the government carry out a strategic and permanent withdrawal from these areas, to enable it to establish more robust defence lines around its strategic strongholds in Damascus, Homs, Hama, Aleppo, and the coast.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Tehran is unlikely to boost military aid significantly, given Assad's recent losses.

- The risk of pro-regime and Hezbollah forces launching an attack on Israel from southern Syria will decrease.

- Sectarian violence in western Syria is likely to rise.

- Regime cohesion appears likely to hold unless it suffers a quick succession of spectacular military defeats.

- International-mediated talks and local truce efforts will not yield results.

Analysis

Rapid rebel advances across the country throughout 2012 forced the regime to undergo its first strategic withdrawal by abandoning much of the countryside and concentrating on the defence of large cities (Aleppo, Damascus, Hama, Homs), military bases, and essential communication lines (including the Damascus-Homs highway and the desert bypass connecting Hama to Aleppo).

In 2014, the concentration of loyalist forces in those regions created space for rebel advances elsewhere, leading to either temporary setbacks (Kassab, in the mountains of Lattakia; Murik, north of Hama) or permanent losses for President Bashar al-Assad (Khan Sheikhun and the Wadi al-Deif military base, between Hama and Idlib; the southern parts of the provinces of Dera'a and Quneitra) (see PROSPECTS 2015: Syria - November 28, 2014).

Manpower shortages worsen

The regime offensives and counter-offensives have extracted a significant toll on the armed forces, significantly exacerbating the manpower shortage.

This has been clear from recent reports of forced recruitment, material incentives for volunteers, new arrivals of Shia foreign fighters, and the proliferation of popular militias (for instance among the Druze minority in Suwayda and Sunni Arab tribes in Hassakeh).

Rise of forced recruitment, popular militias and foreign fighters suggests worsening manpower shortages

In February 2015, two loyalist offensives further highlighted the problem:

- An operation aimed at encircling Aleppo from the north east partly failed. Hundreds of young, poorly trained fresh recruits were killed or imprisoned.

- For the first time in the conflict, pro-regime media explicitly acknowledged that an operation (the capture of villages at the junction of Damascus, Quneitra, and Dera'a provinces) was led and partly manned by Iranian, Lebanese, and Afghan foreign fighters.

On the defensive

The battle of Idlib city provided a clear illustration of the regime's new defensive strategy. Despite the fact that the rebel attack had been anticipated for a long time, loyalist troops hardly fought for the city, but instead regrouped further south in the Mastume military base.

From there, they seized nearby villages in order to establish a defence line aimed at preventing the rebels from accessing the road that connects Idlib to Jisr al-Shughur, the Alawi heartlands, and the coast.

Minor loyalist withdrawals and rebels advances have also recently occurred in besieged suburbs of Damascus such as Dariya.

The regime's 'southern offensive' launched in February was initially presented as an attempt to reconquer the whole region. However, the operation rapidly stalled, and the rebels continued to advance not only on the southern edge of Dera'a province (Bosra and Nasib), but also in the northern area bordering Damascus province (Kafr Shams, near the regime stronghold of Sanamayn).

Battle for Idlib and southern offensive both suggest regime's shift to defensive strategy

Loyalist sources subsequently indicated that the offensive's goals were far more modest than initially announced, and were essentially focused on reinforcing the southern defence lines of Damascus.

Regional power play

The southern offensive represented a significant show of strength by Iran in southern Syria. This might have had an undesired effect for the regime. Occurring shortly after the Huthi's coup against the Yemeni government, the offensive probably reinforced Saudi decisionmakers' determination to pursue a more proactive, security-led approach to rolling back Tehran's influence across the Middle East.

This appears to have accelerated the Saudi rapprochement with Turkey and Qatar, bolstered its decision to launch airstrikes in Yemen, and spurred it to increase support to Syrian rebels operations on the southern and northern fronts (see SYRIA: North-south divide will ease rebel tensions - February 13, 2015 and see SAUDI ARABIA: Turkish detente to boost regional policy - March 25, 2015).

Regime tensions

The recent military setbacks come against a background of serious tensions within the ruling elite:

- In March the Political Security chief and former Syrian proconsul in Lebanon General Rustom Ghazale was beaten to death by the bodyguards of Military Intelligence chief Rafiq Shahade. The reasons for the assault remain mysterious, with rumours ranging from retribution for Ghazale's criticism of Iran's growing role in Syria, to a dispute over the victim's involvement in gasoline trafficking.

- The recent arrest of the president's cousin, Munzir al-Assad, in Lattakia has been attributed to either his mafia-like activities, or his alleged plotting with Bashar's exiled uncle Rif'at al-Asad, who maintains close ties with the Saudi monarchy.

Over the last weeks, the only real piece of good news for Assad has been the prospect that the possible end of economic sanctions against Iran might provide his patron with additional financial resources to shore up his regime.

Assad's losses will make it more difficult for Tehran to justify increasing support

However, sanctions are only likely to be lifted on a gradual basis, and from 2016 at the earliest. Moreover, Iranian money cannot make up for manpower shortages. Tehran's determination to provide more boots on the ground is questionable given that total victory now seems completely out of reach.

Outlook

The regime's new defensive strategy poses inherent challenges to insurgents who lack the heavy weaponry required to take on hard targets. Dramatic military developments are therefore unlikely in the short term, and the stalemate will persist.

The regime's strategic withdrawal will stabilise frontlines, but its forces may still carry out tactical, limited offensive moves aimed at securing its new defence lines (for instance in the anti-Lebanon mountains, the countryside north of Homs, and the Lattakia mountains).

The stalemate will only be broken once the regime's manpower is worn down to a level that requires it to carry out new retreats. This is most likely to happen in the provinces of Dera'a, Aleppo, and Hama, where the regime lacks strategic depth and/or human resources.

_350.jpg)