TPP will unsettle East Asia's regional relations

The TPP agreement reached on October 5 will play into regional politics long before economic impacts are felt

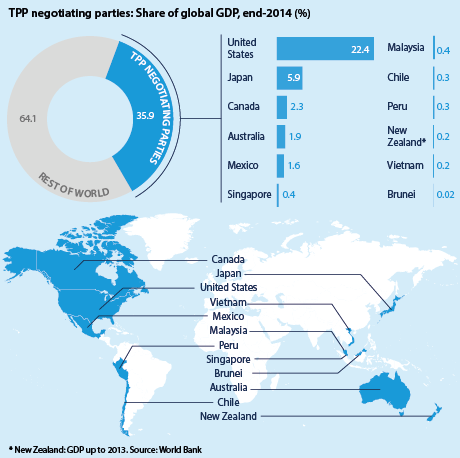

On October 5, representatives from the twelve countries negotiating the expansion of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) free trade agreement reached a preliminary agreement. The agreement, once ratified, will create a new trade bloc that encompasses 36% of global GDP.

What next

The TPP's future hinges on US ratification. Assuming this hurdle is cleared, the economic benefits of the TPP will be modest and slow in coming. The economic and geopolitical threat to China may be similarly overstated, but will spur diplomatic initiatives and perhaps also reform efforts at home.

Subsidiary Impacts

- US congressional politics could quickly undo years of diplomatic work.

- Malaysian domestic politics could be another stumbling block.

- South Korea may be the next economy to join; Taiwan's entry will be much slower.

- The political benefits will probably outweigh the costs for Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

Analysis

The US economy is larger than all the other TPP members combined

Japan-US axis

Japan and the United States are the largest participating economies by far, accounting respectively for 16% and 62% of the new bloc's GDP. The October 5 agreement at last settles issues of protracted contention between them.

Agriculture

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe joined the TPP negotiations promising Japan's farmers that tariffs would be retained on sensitive agricultural products despite US insistence on across-the-board tariff elimination.

The final agreement keeps tariffs for beef, pork and wheat but at a much reduced rate, while the 778% tariff on rice will stay but the tariff-free quota will expand to around 10% of imports.

The agricultural element of the TPP is Abe's first major policy push on which his party is divided -- between those with ties to corporate Japan and those with ties to rural constituencies that wield disproportionate electoral power.

As such, pursuing the TPP could for the first time unsettle Abe's position within the ruling party. However, he has already pushed through reforms of the agricultural sector without apparent political damage (see JAPAN: Abe takes on farming lobby, paving way for TPP - February 17, 2015).

Even the agricultural sector does not wholly oppose the TPP. Abe has positioned himself as a champion of commercial agriculture. Part of his 'third arrow' economic restructuring agenda is consolidating and upgrading the sector to make it more efficient and internationally competitive. The full-time commercial farmers who will benefit from this are more sympathetic to TPP membership than those with traditional family farms.

Japanese agriculture will change even without the TPP

Moreover, the changes will be phased in over periods of nine to 16 years. That interval could see significant changes in the sector anyway as a generation of elderly part-time or amateur farmers hands over to successors less attached to farming and to rural life.

Autos

Corporate Japan is largely in favour of the TPP and stands most to gain from it.

The agreement gives Tokyo concessions in the automotive sector in particular, overcoming a sticking point that until now has been as intractable on the US side as agriculture has been in Japan. The 2.5% US tariff on Japanese automobiles will be eliminated over 25 years, and the United States will eliminate tariffs on 80% of Japanese auto parts.

Abe can therefore point to the TPP as a solid achievement at a time when public confidence in his economic policies has fallen and his September 24 announcement of yet another relaunch of Abenomics (the 'new three arrows') rings hollow with many.

Hanoi hallelujah

The TPP agreement will be received most enthusiastically in Hanoi

With the next National Party Congress just months away, the Communist Party has delivered a major trade agreement in which Vietnam is expected to be the greatest beneficiary in the early years.

Reformers within the government are particularly pleased, because external agreements have proved to be the most effective push for difficult internal adjustments (see MALAYSIA/VIETNAM: TPP deal is likely by year-end - July 23, 2015).

Malaysian misgivings

In Malaysia the finalisation of the TPP comes at a more difficult time. Prime Minister Najib Razak is closely identified with the TPP, and he has a growing number of adversaries, both outside and within the ruling party (not least former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad) who have used controversies over the TPP -- pharmaceuticals are a particular problem with the public -- to attack him.

Najib is embroiled in a financial scandal that includes a US Department of Justice investigation. His days in office may be numbered, and a tumultuous political transition could hinder approval of the TPP and its implementation in the early years.

China challenged?

The TPP is sometimes described as the economic counterpart of the US 'pivot to Asia', implying that it is deliberately crafted to exclude China in order to divert trade and investment elsewhere and marginalise China economically. Many in China regard the TPP as a US-Japanese plot to weaken and 'contain' China economically.

Such an outcome would no doubt be welcomed by hawks in Washington, and the idea helps the White House sell the TPP across government.

In April, Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter remarked publicly that passing TPP is "as important as another aircraft carrier". He did not refer specifically to China, but the Department of Defense does view the TPP as a means of strengthening US alliances with regional partners and overall military strength in the Pacific.

The TPP has a clear geopolitical element

Washington's foremost goal, however, is to establish norms of global trade and investment on terms that benefit US business.

China's choices

China is not necessarily hostile to TPP membership, though Washington and Tokyo are not eager to discuss terms yet, and some in Japan see it as an 'answer' to China's Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (see CHINA: AIIB will reshape development finance landscape - March 30, 2015).

Some in China invoke the presumed threat from the TPP in their arguments for domestic economic reform. Pre-empting the TPP is believed to been one factor behind the launch in 2013 of the Shanghai Free-Trade Zone and announcement in December 2014 of similar Zones in Tianjin, Guangdong province and Fujian province (see CHINA: Free trade zones will strengthen capital flows - May 8, 2015).

Yet the damage China suffers from exclusion may be more theoretical than real: China's economy is too large and well-integrated to be easily bypassed and what losses it does suffer will be small in the context of its huge national economy.

The TPP's decades-long phase-in period means any damage to China will be slow in coming. By then, China's economy will look very different.

The TPP's stipulations on labour, state-owned enterprises and intellectual property are problematic for Beijing at present, but membership will become more attractive as China's economy comes, as it must, to rely more on innovation and intellectual property, as its businesses become more competitive internationally, and as Beijing raises environmental and labour standards for domestic reasons.

Moreover, China's economy is so large that it could plausibly bargain for special treatment that allowed entry without such onerous concessions as smaller developing countries have had to accept.

It is also plausible that Beijing might sign up to unwelcome conditions and then procrastinate on implementation as long as the benefits of violating its commitments outweigh the penalties.

Alternatively, China's huge domestic market makes it appealing as a bilateral FTA partner, and such agreements allow Beijing to bargain more flexibly for more favourable terms, as it recently has with US allies Australia and South Korea.

Beijing could thus build a hub-and-spoke pattern that makes TPP membership unnecessary and gives China better terms. Talks on bilateral investment treaty with Washington and a trilateral FTA with Seoul and Tokyo merit watching here.

Other non-members

The agreement affects other non-member countries too.

Thailand troubled

As a US treaty ally, Thailand might have been expected to join. However, political instability throughout the seven years of TPP negotiations made Bangkok a problematic negotiating partner and Washington is unlikely to open new negotiations as long as Thailand remains under military rule. The collapse in 2006 of negotiations on a bilateral US-Thailand FTA, primarily over pharmaceuticals, also sets an unpromising precedent.

Bangkok is also sensitive to China's exclusion from the TPP. The junta cannot risk alienating its important economic and diplomatic ally while it holds off reintroduction of democratic rule (unlikely at least until mid-2017).

Yet non-membership will not make Thailand immune to its impact. Notably, Thai rice farmers fear that increased US-Japan and US-Vietnam agricultural trade would undercut Thai rice exports, which have already lost market share to Indian and Vietnamese rice since 2011.

On the upside, albeit over the medium term, the gradual erosion of US tariff barriers on Japan's automotive industry promises benefits via their with supply chain links to Thailand.

Indonesia immune?

Indonesia has not joined. It is not an export-dependent economy, and its exports are mainly natural resources for which world prices rather than trade barriers are the key variable.

However, increased exports of Malaysian palm oil within the TPP risk undercutting Indonesian exporters, exacerbating the negative impact of the wider commodity price slump.

Taiwan tarries

Taiwan's ruling Kuomintang party has pushed hard for TPP membership, and the main opposition Democratic Progressive Party -- which is likely to capture the presidency and legislature in January 2016 elections -- is equally eager, though some domestic opposition will slow things down.

Taiwan's next president will have to pass laws to prepare for membership, eliminating restrictions on US beef. After January's elections, the TPP will receive a lot of attention, but given the slow pace of legislation in recent years, substantial progress could be several years away.

For Taipei, the benefits of membership are not just economic; it would raise Taiwan's profile as an autonomous actor in international affairs. Because the TPP is APEC-based and APEC membership comprises 'economies' rather than governments, technically Taiwan could join, though Beijing would insist on formal naming that emphasises 'China' rather than 'Taiwan'.

For similar reasons of political symbolism, Beijing may not want Taiwan to join until and unless China itself does, and could lean heavily on other countries to block this. The perception in Washington is that admitting Taipei before Beijing would cross a red line with Beijing.

South Korean exception?

South Korea is the strongest candidate for membership

TPP membership is less urgent for South Korea than for Taiwan. For Seoul the proposition is wholly economic -- it has no political point to prove. Moreover, South Korea leads the region in terms of FTAs, having already signed them with China, the EU and the United States. As such, the marginal benefits of membership may be lower.

However, Washington is eager to include Seoul and it might even be possible for South Korea to negotiate entry before the next tranche of entrants.

US hurdle

The TPP is not a done deal yet: it must still be signed and ratified by all parties.

The highest hurdle is in Washington, where it will meet opposition in Congress from states with significant automobile, tobacco and pharmaceutical industries, who will need to keep on good terms with these interest groups ahead of the 2016 election cycle:

- The automobile industry did not get the measures it wanted on 'rules of origin' for auto parts and measures to retaliate against countries practicing 'currency manipulation'.

- The tobacco industry opposes a measure that prevents tobacco companies suing foreign governments over anti-tobacco regulations.

- The agreement gives pharmaceutical companies a shorter monopoly period on 'biologics' drugs (eight years) than they currently enjoy in the United States (12 years).

However, partisan politics also plays into congressional opposition.

President Barack Obama expects continued resistance from Hill Democrats, particularly from the labour-aligned 'progressive' wing of the party, but a number of key Republicans have also found problems with the agreement announced by the US Trade Representative.

Despite the general pro-trade leanings of their party, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, Senate Finance Committee Chair Orrin Hatch and House Committee on Ways and Means Chair Paul Ryan have all made statements sceptical of the TPP's benefits to their constituents.

Although Congress has granted Obama trade promotion authority, which limits the ability of the legislature to amend the TPP or hinder its passage, Congress could still obstruct the White House's trade agenda.

When Congress is allowed to vote on the ratification in early 2016, it may vote down the pact on the assumption that the other eleven TPP members are willing to wait and re-open negotiations until the US gets an agreement that it can accept.

In any case, the actual terms of the agreement -- negotiated in secret -- will not be available to Congress or the various stakeholders for at least 60 days before Obama formally signs the deal, which will give the administration some time to marshal its arguments and support on Capitol Hill.

Several partisan dynamics are in play. Congress narrowly sidestepped a government shutdown in September, but Republicans may be reluctant to cooperate with the White House ahead of the next round of spending negotiations and the 2016 elections.

Republicans may seek to delay ratification until 2017 if they believe their party can win the presidency, to deny Obama a policy victory to burnish his political legacy, as was the case when the Democrats prevented the George HW Bush administration from securing ratification of NAFTA in the early 1990s.

_350.jpg)