New 'de facto' states could reshape the Middle East

Conflict is accelerating state fragmentation across the region

The 2011 uprisings exposed the weaknesses of the region's political systems and state institutions, highlighting their failure to meet their population's aspirations. This was particularly the case in countries created on artificial colonial boundaries that contain a diverse range of ethnic, sectarian and tribal groups. The conflicts that emerged from the uprisings look set to accelerate the fragmentation of the state in these areas.

What next

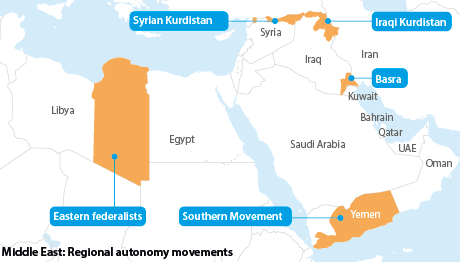

The twin drivers of weakening central governments and the emergence of new self-governing entities could alter the shape of the region over the next decade. With existing states buckling, these new 'de facto' states could help de-escalate conflict and improve stabilisation prospects. Such entities are most likely to form in Syrian and Iraqi Kurdistan, while southern Yemen and eastern Libya could gain significant autonomy under new federalist agreements.

Subsidiary Impacts

- In the short term, the creation of new ethnic- or sectarian-based self-governing entities will increase the risk of ethnic cleansing.

- Allowing self-government without formal recognition of secession can yield sustainable peace and stability.

- The survival of these new entities will depend on their economic viability as well as acquiescence from the 'parent state' and neighbours.

- Their stability could be jeopardised by external actors seeking to use them as proxies in regional power struggles.

Analysis

As central governments in the region have weakened, secessionist and regional autonomy movements have increased in number and strength.

The most significant ones have prior histories of communal autonomy or statehood:

- The Kurds say they are seeking to rectify their exclusion from the post-First World War settlement which defined the region's borders.

- In Yemen, the Southern Movement seeks to reinstate south Yemen, abrogating the unification of 1990.

- In eastern Libya, armed factions are seeking to restore Cyrenaica as an autonomous entity, as under the country's first federal constitution (see LIBYA: Oil sector relocations strengthen federalists - June 27, 2013).

Secessionist and regional autonomy movements are often based around ethno-sectarian or tribal-provincial groups that seek to end perceived marginalisation by central regimes. They are driven by strong economic and social grievances, and a sense that the central government has privileged other regions in economic development and redistribution of the national wealth.

This is particularly the case in provincial regions with abundant natural resources, such as the oil-rich regions of Iraqi Kurdistan and Basra; Hadramaut in southern Yemen; and Cyrenaica in eastern Libya. They seek greater control over the oil resources that fall within their territory (see IRAQ: Baghdad will head off Basra autonomy bid - June 18, 2015).

Capturing the state

Some movements have begun to operate increasingly like states themselves, controlling considerable territory, operating their own security and judicial services, and offering economic, social and cultural services.

Yet not every aggrieved political community demands autonomy or independence. Some have sought greater influence within existing state institutions. This can lead to conflict and even outright state capture.

In Iraq, Shia groups took control of the previously Sunni-dominated government institutions under the post-2003 war settlement. This was a result of the Shia population's numerical advantage in the country's new sectarian-based electoral system.

In Yemen, a northern provincial militant movement, the Huthis, took over central government by force in September 2014, exploiting the post-2011 power vacuum.

Federalist option

Without the means to defeat these groups militarily, Arab states have turned to federalism as a solution. However, this is not always effective in dealing with demands for secession or regional autonomy, as it can exacerbate tensions.

The Kurds in Iraq accepted federalism as part of the 2005 constitution, but are dissatisfied with their allocation of oil revenue in the federal budget and the boundaries of the federal region.

During the civil war, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad promised federalism to appease Kurdish nationalists. However, such proposals are deeply unpopular with their Arab neighbours in north-east Syria; and with Syrian Arab nationalists who oppose any dilution of the state's Arab character.

Federalism is a divisive issue that can exacerbate tensions

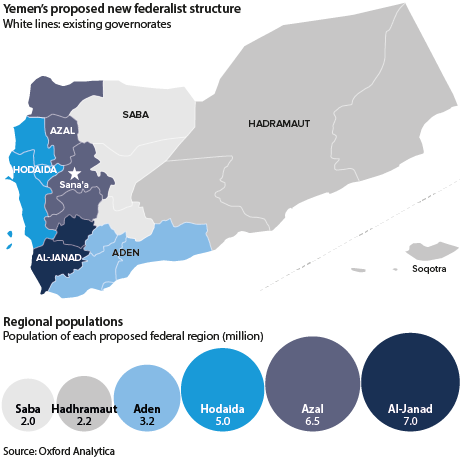

Federalism was discussed as the most realistic option for Yemen following the ouster of President Ali Abdallah Saleh in 2011. However, the southerners rejected a plan that offered to create six federal regions, with only two regions allocated to the south compared to four for the north (see YEMEN: Federalist system will reshape political map - April 23, 2014).

Beyond the oil-rich province of Cyrenaica, federalism appears very unpopular among Libyans, and is often decried as a means to split the country apart.

Potential partners for international actors?

Outside powers have sought to find ways to engage these groups through the provision of military, economic or other kinds of assistance:

- The United States has a strong, longstanding relationship with the KRG.

- It has recently allied with the main Syrian Kurdish party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), in the fight against Islamic State group (ISG).

- Russia has reached out to the PYD, partly in an effort to gain leverage over Turkey.

Such pragmatic moves are necessary in the absence of effective state power. However, the interests of secessionist groups and outside powers do not necessarily align. By arming and supporting such groups, external powers risk strengthening the momentum for regional devolution and secession.

Saudi Arabia has used southern militias to fight the Huthis in Yemen. Southerners will require 'payback' in the form of greater autonomy and resources from central government in any final peace settlement.

Moreover, backing a secessionist group risks antagonising parent states and neighbours, as demonstrated by Ankara's anger at Washington's support for the PYD.

Changing the regional map

Without the return of strong state institutions, the momentum towards regional autonomy and secession will continue. This is likely to change the political map of the region in a number of ways:

Secession prospects

In general, the international community has sought to maintain the territorial integrity of existing states. However, since the end of the Cold War, partition has been more common, as evidenced in Bosnia, East Timor, Eritrea and South Sudan.

International recognition of secessionist movements is especially likely when that movement is able to demonstrate that it can provide security and requires limited changes to international borders. The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) is most likely to meet these requirements. However, key obstacles include the KRG's economic dependence on Baghdad, and Turkey's opposition to Kurdish statehood.

De facto states

Many fragmenting states in the region may see the emergence of de facto states -- stable political entities which possess the internal qualities of statehood, but lack international recognition. Examples include the self-declared Turkish entity in the north of Cyprus, Somaliland and Nagorno-Karabakh.

Although de facto states form through war, over time they often reach stable, non-violent arrangements with the still-nominally sovereign parent states. De facto statehood depends on the parent state's willingness to relinquish operational control over a territory, even though it still maintains a claim to sovereignty.

De facto statehood requires the parent state to relinquish operational control over an area

De facto statehood can help improve stability by appeasing secessionist demands for substantial self-rule and separation from a parent state. It can also provide governing institutions capable of handling humanitarian crises, such as the inflow of refugees, and counter-terrorism operations.

This type of arrangement is already evident in the KRG. De facto statehood is becoming increasingly likely for the Kurds in Syria as well. The prospects of stable de facto statehood are less strong in Libya and Yemen. Federalist solutions have not yet been fully tested in these countries and may have greater attractiveness.

_350.jpg)