Temer would seek orthodox policy turn in Brazil

A Temer government would pursue economic orthodoxy, but unpopular reforms could rapidly shake an unwieldy coalition

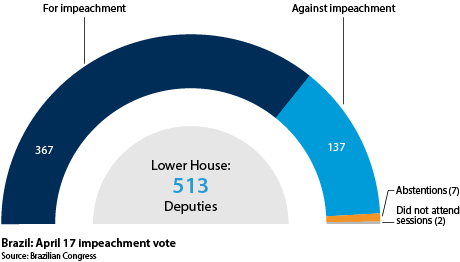

The Lower House yesterday approved the continuation of impeachment proceedings against President Dilma Rousseff by a vote of 367-137, with seven abstentions and two absentees. The impeachment process will now be sent to the Senate. If a majority of the 81 senators accept its continuation, Rousseff will be suspended initially for 180 days while the Senate makes a final decision. Vice-President Michel Temer would replace her, initially at least in a temporary capacity. The increasing possibility of a Temer government has increased interest in the policies he would seek to tackle Brazil's profound recession.

What next

A Temer government would pursue an economically orthodox agenda, including a number of reforms that would require constitutional amendments. It could enjoy a window of opportunity to pass these politically difficult measures. However, this would be narrow, and the new administration would face a variety of political challenges.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Temer would slash the number of ministries.

- The prospects of more orthodox policies will boost financial markets, but real economic recovery requires private investment.

- Unpopular reforms may quickly unravel a national unity coalition, especially if it can no longer coalesce around an anti-Rousseff position.

Analysis

The vote for Rousseff's impeachment was well above the 342 out of 513 deputies required to advance the process to the Senate.

Temer's Democratic Movement Party (PMDB) is a coalition of regional interests without a unifying ideology. However, as the party moved increasingly towards the opposition in recent months, it embraced an economically orthodox agenda. This was summarised in the document 'A bridge to the future', published in October 2015:

- Constitutionally earmarked spending in areas such as health and education would end. With nearly 90% of federal spending earmarked, the government currently has very little leeway to shape its budget. A corollary is that any austerity effort focuses on slashing investment, which undermines growth.

- Indexation of government spending would also end. A crucial area affected would be the pensions system, as currently the annual adjustment of public pensions is linked to the minimum wage, which rose by 116.3% in real terms between 1995 and 2015 (see BRAZIL: Ageing population raises pension, labour fears - October 22, 2013).

- The minimum retirement age would be no lower than 65 years for men and 60 for women. Currently eligibility for retirement depends on a calculation including a person's age, the number of years they have paid into the system and life expectancy.

- A Zero-Based Budgeting process would be adopted. This is an increasingly popular method in the corporate world, which establishes that all expenditure is reassessed at the beginning of a new tax year, instead of automatically extending existing programmes.

Temer would embrace an economically liberal agenda

The PMDB argues that these measures will allow the state to balance its books and reduce its debt (see BRAZIL: Inflation 'solution' should help avoid default - April 4, 2016).

Other proposals include seeking free-trade deals with the United States, the EU and Asian economies, simplifying Brazil's byzantine tax system and giving preference to collective bargaining over legal rules in salary negotiations, "except when it comes to basic rights".

Policy drawbacks?

The proposals seek quickly to improve the country's poor business environment, a key hurdle undermining growth. However, some of them also risk reversing a number of the country's recent significant social and economic advances:

Inequality

A study by economist Alessandra Scalioni Brito has shown that 72.4% of the 12.2% reduction in inequality in Brazil between 1995 and 2013 -- as measured by the Gini index -- was explained by the increase in the minimum wage. Almost 40% of this was due to the impact of the minimum wage on public pensions.

As of 2013, 54.9% of pensioners and 15.2% of active workers received the minimum wage. Therefore, more modest minimum wage adjustments could potentially provoke an increase in inequality. This would come as Brazil is seeing the first signs of a reversal in its inequality reduction amid the economic crisis.

Yet it is unclear whether further increases in the minimum wage would be an effective tool to tackle inequality or if this policy has reached its limits. Moreover, minimum wage rises without corresponding increases in productivity have undermined the already weak competitiveness of Brazilian firms.

At the same time, other policies, such improvements to the Bolsa Familia cash transfer programme, could replace minimum wage boosts as the main mechanism to address inequality.

Education concerns

Another possible socially and economically negative side effect of the PMDB proposals concerns their impact on education:

- The 1988 Constitution requires that the federal government invest 18% of its revenue on education (25% for states and municipalities).

- This constitutionally earmarked spending prompted a wider process leading to a significant increase in the proportion of children and adolescents attending school.

It is probable that cuts in the share of public spending in education, highly likely if these are no longer earmarked, would risk reversing gains recorded in recent decades.

Governability issues

Temer's window of opportunity to pass reforms would be narrow

Many of the proposed measures are hard-to-sell reforms whose positive impact on the economy would only be seen in the future. Nevertheless, a 'national unity' discourse embraced by centre and right-of-centre parties could temporarily soothe the governance difficulties entrenched in Brazilian politics (see BRAZIL: Governance will become more challenging - September 17, 2015), helping the government pass some of them.

Yet this window of opportunity would be narrow:

- The continuing recession would take its toll on a new government's popularity, creating incentives for members of Congress to oppose it.

- The focus of popular anger may well turn from Rousseff's Worker's Party (PT) to the PMDB and its allies -- especially if there is a perception that a new government is working to slow corruption investigations (see BRAZIL: Parties battle to respond to political crisis - January 4, 2016).

Coalition-building efforts would be facilitated if the PMDB announces it will not present a candidate in the 2018 presidential elections -- although the party is often the largest in Congress, it has not contested the presidency since 1994. Still, as elections draw closer, different parties supporting the government would seek to differentiate themselves from each other and concentrate their energies on the polls.

Furthermore, social movements will oppose a new government fiercely, possibly generating an atmosphere of instability.

All in all, in the best-case scenario, a Temer government would have little more than 12-18 months to implement any meaningful policy changes -- possibly far less than that.

An early end?

Temer himself faces potential impeachment proceedings for reasons similar to those now threatening Rousseff's government -- which is officially being judged for manoeuvring to hide the extent of the fiscal deficit (see BRAZIL: Early Rousseff exit appears ever more likely - March 14, 2016).

In addition, the Supreme Electoral Court (TSE) could still annul the 2014 presidential elections on the grounds that the Rousseff-Temer campaign benefited from donations from construction companies that disguised bribe payments for contracts with state-controlled oil company Petrobras.

That TSE decision, if made this year, would lead to new elections being held. There are also increasing calls -- not least from the PT -- for a new presidential vote to be organised this year whatever the TSE's final say.

_350.jpg)