Spain's labour market will remain source of fragility

Demographic change will eventually ease unemployment, but put greater pressure on the social security system

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the Spanish government introduced significant structural changes. These included reforms of the labour market and the pension system, together with several active labour market policies.

What next

The next government will have to review the recent reforms to regain the confidence of the electorate, underpin growth and ensure the sustainability of the pension system. Lack of adequate employment opportunities for young people may lead to further emigration and may be associated with individuals postponing marriage and major financial commitments (notably property purchase), lower birth rates and disillusionment with government. The latter may be reflected in increasing fragmentation of politics and continued support for the 'progressive' left.

Subsidiary Impacts

- A new government after the election on June 26 could end the political deadlock and implement measures to encourage further job creation.

- Job insecurity and the lack of permanent full-time contracts will continue to weigh on household demand.

- The north-south divide will make reforming regional finances a hotly contested issue in the next legislative period.

Analysis

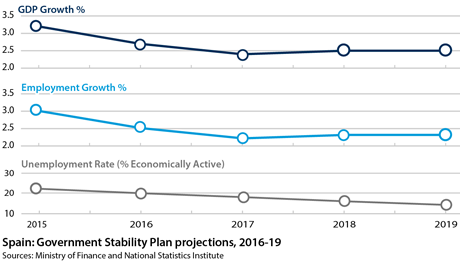

The Spanish economy emerged out of the 'great recession' in 2013, with GDP growth of 1.4% in 2014, 3.2% in 2015 and, according to forecasts, around 2.6% this year. Growth has been accompanied by the creation of around 1 million jobs in the last two years; a further 450,000 are expected to be created this year.

Unemployment has fallen, although the official rate at the end of this year is still expected to be around 20%. Even by the end of 2019, the government forecasts an unemployment rate of 14% (3 million people), far above pre-recession levels.

Regional differences

There are marked geographical variations in unemployment, with a distinct north-south divide. South of Madrid, in Andalusia, Castilla-La Mancha and Extremadura, the regional unemployment rates in the first quarter of 2016 were 25-30%, with some provinces in Andalusia recording rates close to 40%.

In contrast, to the north of Madrid, rates are generally below the national average. The lowest rates (below 15%) are recorded in two regions with high degrees of fiscal independence and strong export sectors, the Basque Country and Navarra.

Youth unemployment

Labour market reforms, especially those implemented in 2012, have increased labour market flexibility, decreased the cost of redundancies and contributed to low annual wage increases. However, they and other active labour market policies have done little to erode the dual labour market and increase the proportion of permanent labour contracts.

Fewer than 10%

Permanent labour contracts as a proportion of all contracts signed between January and April 2016

Unemployment rate

According to the latest quarterly National Employment Survey, at the end of the first quarter of 2016, the total number unemployed had fallen to 4.8 million, down from 5.4 million a year earlier (a rate of 24%) and 6.3 million (27%) at the end of the first quarter of 2013.

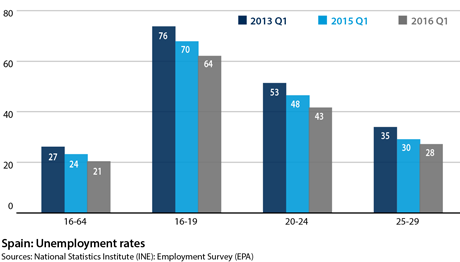

However, the recession affected young people in particular, and they have continued to suffer during the recovery (see EU: Growth alone will not solve youth unemployment - August 27, 2015). Their unemployment rate has remained much higher than the average.

For the small economically active group aged 16-19 (some 220,000), the unemployment rate is now 64%, down from almost 76% at the end of the first quarter of 2013. For the much larger cohort of economically active people aged 20-24 (1.2 million), the rate is 43% and for those aged 25-29 (2.1 million), 28%.

Participation rate

The economic activity rate, or the proportion of individuals in or actively seeking employment, has fallen significantly among young people. In an environment with few jobs, or at least few desirable jobs, discouragement and economic inactivity have spread.

The total number of economically active individuals increased to peak at around 23.5 million in 2012; it has since fallen back to some 23.0 million, with the economic activity rate (for those aged 16 and above) falling from 60.5% to 59.3%.

Again, this drop has been particularly pronounced among young people. For those aged 16-19, the activity rate has fallen from over 30% before the crisis to only 13%. For the those aged 20-24, the rate has fallen from around 67% to 54%, while for those aged 25-29 the fall is less significant, from around 87% to under 85%.

Spain's new lower class

Unskilled young people are turning into the new Spanish lower class. Where they have been able to find employment, it is seldom on an open-ended contract.

346,000

Number of under-30-year-olds unemployed for at least two years in the first quarter of 2016

In April 2016, fewer than half (49%) of the around 13 million people in the largest category of the social security system were on full-time permanent contracts. Of these, fewer than 2% were under 25 and fewer than 9% under 30. Many young people have only gained professional experience through casual work in the hospitality and catering industry; previously, they found such work in the construction sector. It is these, often low-wage and unskilled jobs, that continue to provide a large proportion of the new job opportunities.

Demographic change

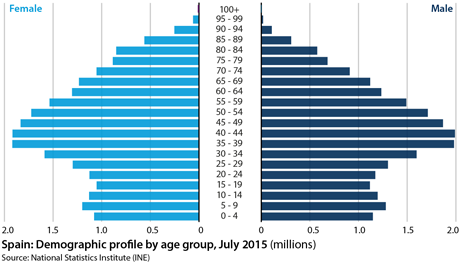

Total rates of unemployment mask important demographic changes.

In many European countries including Spain, the rate of natural population growth has fallen to a level close to or below replacement (see EUROPE: Demographic trends will force social reforms - June 27, 2012). Low natural growth had been buoyed by a net migration gain until 2012, which since then has reversed into a net migration loss.

Spain's population is ageing and the dependency ratio growing

A combination of natural population decline with little support from net migration has led the National Statistics Office (INE) to project a continued fall in the population over the coming years, from 46.5 million at the beginning of this year to 45.5 million by 2030, with further falls beyond that.

In the absence of large-scale immigration or a significant rise in birth rates, the number of people in the current 16-64 working age group will decrease through to 2050. This will become especially marked from the mid-2020s, when annual reductions are projected to rise towards 250,000 a year, reversing the current unemployment problem into a labour shortage.

Equally, the INE projects the dependency ratio (those aged below 16 and above 64 as a ratio of those aged 16-64) to rise from just over 50% to almost 60% in 2030 and 95% by 2050, with obvious implications for the social security system. However, these figures are projections rather than forecasts. The migration balance could once again shift and recent reforms to the pensions system envisage people working into their late 60s.

_350.jpg)