Iraq will keep Shia militias out of Mosul

Although barred from the main offensive, Shia fighters are seeking a long-term political role

Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi today announced the launch of the long-awaited offensive against Islamic State (IS) in Mosul. He stated that the Iraqi army and police "are the ones that will enter Mosul, not others", emphasising the exclusion of the Shia Popular Mobilisation Units (PMUs), which have played a controversial role in the recapture of other majority-Sunni cities. The PMUs have instead been deployed to the west, to cut off IS's line of retreat to its Raqqa stronghold in Syria.

What next

IS will be unable to hold Mosul, although the offensive could take many weeks. Afterwards, the PMUs will seek a long-term role in provincial and national politics. The Shia religious leadership may order their demobilisation ahead of provincial and national elections in 2017 and 2018, respectively. However, the PMUs will resist calls to disband, coming up with new rationales for their presence in Baghdad, on the Kurdish frontier and in the oil-rich south. Their support could strengthen former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki against Abadi, his successor and rival.

Subsidiary Impacts

- If efforts to keep the Shia PMUs out of the urban battle in Mosul fail, this would complicate stabilisation efforts.

- The revival of Maliki's influence could undermine plans to keep paying the Sunni forces among the PMUs.

- After Mosul, IS will change its mode of operations, mounting more bombing attacks, especially in Baghdad.

Analysis

The PMUs, or Hashd al-Sha'abi, comprise around 160,000 predominantly-Shia armed volunteers, who fight alongside the Iraqi security forces (ISF). Many units formed in response to a call for popular mobilisation by Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the country's senior Shia cleric, after IS took Mosul in June 2014.

However, the PMUs also include many pre-existing Iran-backed Shia militia elements, which were active in the periodic violence seen in 2003-11.

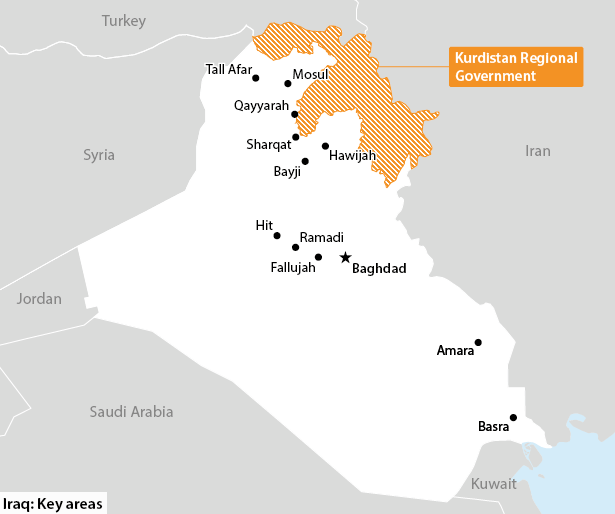

The PMUs were vital to the defence of Baghdad against IS in June 2014. They were the dominant fighting force until May 2015, when the US-supported ISF took over the failing battle of Tikrit, expelling IS. Subsequently, the army has led successful offensives against militants in Ramadi, Bayji, Hit, Fallujah, Qayyarah and Sharqat.

Shia PMU presence concerns Sunnis

As the frontline has moved north, increasing numbers of Sunni fighters have been recruited, forming separate tribal units working under army command. Meanwhile the Shia PMUs have played a declining role: their forces are overstretched and less welcome in Sunni areas in the north.

Mosul exclusion

The PMUs are specifically excluded from the urban battle for Mosul. The government and US-led coalition hope that this will improve the chances of a positive post-liberation reaction by the mainly-Sunni population, who fear sectarian persecution by the PMUs.

Around 6,000 Sunni fighters and local police are instead assisting the main ISF assault from the south, with the US-led coalition providing air support. Other irregular forces have been given separate roles to reduce the risk of infighting.

Kurdish peshmerga fighters are attacking IS-held villages to the east of the city. Meanwhile, the PMUs are cutting off retreat to the west. They are likely to focus their efforts on two satellite battles in the smaller cities of Hawijah and Tall Afar -- although some militia leaders may still seek to enter Mosul to take propaganda pictures.

Demobilisation?

The expulsion of IS from Mosul and surrounding areas may be completed by early 2017, removing the original rationale for the existence of PMUs. In that case, Sistani could issue a new fatwa, rescinding the religious obligation for Shia to volunteer against IS. This would remove the religious cover and legitimation enjoyed since June 2014 by pre-existing Shia militant groups such as Asaib Ahl al-Haq and Kataib Hezbollah.

Mainstream Shia factions might seize the opportunity to act against them. Already, in areas around Baghdad, there are signs that larger Shia political-military complexes, such as the Badr Organisation, are cracking down on Asaib Ahl al-Haq, a smaller militia that has been linked to sectarian massacres and kidnappings.

Mainstream Shia elements seek to control the PMUs

Abadi is also moving to bring PMU elements more firmly under government control. He issued an executive order on February 22 reiterating his authority to "restructur[e] and reorganiz[e] the Hashd al-Sha'abi organization", with the aim of enforcing military discipline.

This reflects a public fear, among many Shia as well as Sunnis, that some militias are committing human rights violations and criminal acts.

New roles

If the PMUs are not disbanded, there is a risk they could develop into a parallel security state, along the lines of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) or Lebanon's Hezbollah. Funding will be a key indicator. The PMU commission was allocated 1.2 billion dollars in 2016. If it receives a multi-billion-dollar allocation in the 2017 budget, this would suggest it might develop into a permanent agency.

The US-led coalition might even encourage the government to maintain at least some of the Shia PMUs in order to lock in funding for Sunni units. The latter will be needed to act as 'hold forces' in liberated northern cities. After the US withdrawal in 2011, problems paying the salaries of Sunni volunteers in the Sahwa (Awakening) movement contributed to the original rise of IS.

The PMUs could establish local dominance

The PMUs will look for new military reasons to justify ongoing mobilisation, regardless of calls by the Shia political and religious mainstream. Potential new roles include:

- Protection of Baghdad and Shia centres.If IS mounts increasing numbers of mass-casualty attacks against the Shia, the PMUs will be quick to claim an overt armed role in the protection of Shia neighbourhoods, religious sites and processions. This could escalate: retaliation against Sunni areas might help IS to retain a foothold in some districts.

- Defence of the Kurdish frontier. Shia PMUs are already signalling that they should be used by the Iraqi state as a frontier force capable of pushing back the Kurdish presence along disputed boundaries in northern Iraq. Factions in the Baghdad government may welcome a militant proxy to pressure the Kurds on territorial, resource-sharing and independence issues.

- Control of the southern provinces. The PMUs will have room to operate as local warlords in the oil-rich southern provinces as long as the bulk of ISF strength is focused on securing western and northern Iraq. By the time the army redeploys to its home bases in 2017-18, there may be a deeply embedded Shia militia problem in vital economic hubs such as Basra and Amara.

Political ambitions

Iraq's provincial elections are scheduled for 2017, though they may be folded together with national elections due in 2018. If the local polls are run separately, they may indicate whether PMU factions can convert their military cohesion into political success, mobilising their supporters as a block vote.

Maliki has floated the idea of expanding his State of Law Alliance (which also includes Abadi's supporters), incorporating PMUs such as Badr, Kataib Hezbollah and AAH. If successfully mobilised in the voting booth, the PMUs could also become a major factor in the national elections, reviving Maliki's chances of a return to the premiership.

_350.jpg)