Trump will follow Obama’s policy on Syria

Despite the president's rhetoric, the strategic situation in the Levant leaves his administration with few alternatives

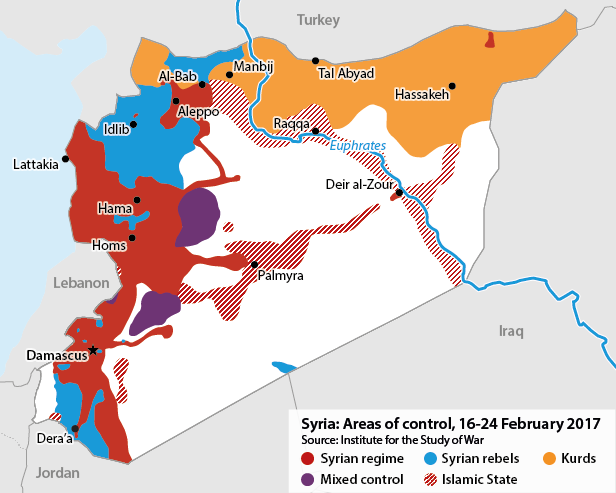

The top US general fighting Islamic State (IS) in Iraq and Syria, Stephen Townsend, yesterday said that he was talking to Ankara about the role it might play in capturing the jihadi group’s Syrian ‘capital’, Raqqa. He suggested that this offensive would not involve a major US troop increase; Washington must therefore decide whether to cooperate with Turkey or Turkey's enemies, the Syrian Kurds -- who were yesterday mistakenly bombed by Russian planes. Donald Trump’s presidency has coincided with pivotal developments in Syria, including the insurgency’s strategic defeat, the consolidation of Turkish and Russian positions, and the ongoing routing of IS in the north.

What next

There will be significant policy continuity between the Obama and Trump administrations, partly because evolving events in Syria constrain US options. Moreover, the views of key senior White House advisers to each president share important elements. Thus Trump is likely to maintain Obama’s focus on the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) as the United States’ main anti-IS partner, with consequent tensions with Turkey. His one new policy option -- establishing ‘safe zones’ -- is likely to fail if implemented.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Unless they are needed to police safe zones, Washington’s provision of arms to Syrian rebels is likely to decline, especially as IS weakens.

- Washington will not prioritise a ‘political transition’ in Syria: the civil war will go on, with the regime in a dominant military position.

- Trump’s anti-Obama campaign rhetoric on Syria may force him to dress up old policies in new colours.

Analysis

US Secretary of Defense James Mattis briefed the White House on February 27 on the Pentagon's draft plan for defeating IS. The Department of Defense may be given more leeway to shape anti-IS policy under Trump than Obama. The focus of its current draft plan is global, but it will inevitably include significant elements on both Syria and Iraq (see IRAQ/UNITED STATES: Tensions could degrade cooperation - February 10, 2017).

Despite Trump's aggressive criticism of his predecessor's strategy as weak and insufficient, he and his advisors are more likely to adjust than to overhaul it. For very different ideological reasons, the two presidents share a basic belief that it should not be the US role to intervene heavily in Middle Eastern countries, ruling out a major use of ground forces.

Syrian priority

Washington is therefore likely to maintain the existing 'path-of-least-resistance' strategy of deploying US aircraft and special forces to support an assault on IS's Raqqa stronghold by the SDF, which is dominated by Kurdish Syrian rebels (see SYRIA: Kurdish-Turkish spat may save Islamic State - December 21, 2016). Other potential allies against IS are linked either to radical Sunni Islamist groups or to Iran -- both unpalatable partners for the Trump team.

The speed and casualty toll of the SDF assault on Raqqa may be improved by possible minor adjustments to US policy; namely, loosening the rules of engagement and deploying a few hundred conventional US troops in close support roles or possibly closer to the frontlines.

This will enrage Turkey, which dismisses the Syrian Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG) as terrorists linked to its internal Kurdish rebels, and has put forward two planned routes to take Raqqa with its own Syrian rebel proxies, the Free Syrian Army (FSA). The FSA has just expelled IS from Al-Bab, after a long campaign with heavy Turkish support.

However, Ankara will probably fail to present itself as a viable alternative to the SDF. The Trump administration will be wary of Turkish ties to salafi rebel groups such as Ahrar al-Sham, and of being pulled into their ongoing war with the government of President Bashar al-Assad and his ally, Russia (see SYRIA: Damascus will balance Moscow and Tehran - February 9, 2017).

Even if the United States helps the Kurds to take Raqqa, holding it will be hard

Turkey may therefore act as a spoiler to the SDF assault on Raqqa, arguing that Kurdish-dominated forces should not be allowed to take an Arab city. The FSA is already planning an assault on the town of Manbij, previously captured by the YPG: this could be a staging post on its road to Raqqa, unless Washington takes a strong deterrent position.

Under those circumstances, the SDF might struggle to hold Raqqa. Infighting among its enemies, combined with the YPG's poor record of sharing power with local Arabs, could even potentially enable an IS comeback.

Beyond Raqqa

Mattis has indicated that he favours a holistic counter-IS strategy that goes beyond the military to include disrupting IS finances, countering its ideology and its root causes. The Obama administration had some success countering IS finances, upon which Trump could build.

Washington cannot pressure Damascus to tackle IS root causes

However, tackling root causes in Syria would necessitate addressing at least some of the sectarian and political grievances among the Sunni Arab community. Since those are intimately tied to the civil war, in which Washington has no appetite to engage, the anti-IS effort is indeed likely to be overwhelmingly military and heavily focused on capturing key territory, especially Raqqa. Trump and his team will also have to decide how to address IS's control the of the Euphrates river valley around Deir ez-Zour -- complicated by the fact that its main opponent here is the Assad regime, not a US ally.

Another key decision will concern how anti-IS efforts in Syria are linked to wider efforts to take on jihadi groups globally. The Pentagon's specific proposals are not yet available, but Trump is likely to prefer a broader, more aggressive conflict with all regional extremist groups.

One such group is Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a former al-Qaida affiliate with power bases in northern and southern Syria, which will almost certainly come under heavy US military pressure. However, Washington's only available partners on the ground fighting HTS in these areas would be either Tehran-aligned pro-regime forces or rival salafi rebel groups. Neither is likely to appeal to the Trump administration, which will therefore be left with Obama's counterterrorism policy of surveillance, penetration and targeted killings.

Safe zones?

Trump has repeatedly promised to set up 'safe zones' in or near Syria. Securing any such area would be difficult and risky, but the matter is reportedly under serious consideration. This would be the most significant break from the Obama administration, which consistently rejected such options.

If implemented at all, these would be basic havens for the displaced, rather than 'no-fly zones' under US military protection, in which Syrian opposition groups could operate. To minimise risks, Washington would probably aim to exploit current pockets of stability rather than attempting to pacify conflict-affected areas. Geographically, that makes the Turkish-controlled areas of Aleppo province or the southern border area near Jordan the most likely candidates -- although disputes over the Kurds might derail the Turkish option.

Any safe-zone strategy would have to specify who is to pay for them, police them, enforce them and punish violations (see SYRIA: Reconstruction plans will multiply - January 30, 2017). Washington would also have to figure out how to persuade Moscow, Tehran and Damascus to respect such an arrangement. Finally, it would need to formulate a strategy to manage efforts to exploit the situation by insurgent groups (including IS and HTS).

Sources close to Pentagon planners suggest that any planning for safe zones is in the conceptual rather than the operational stage. It is possible that once these details are examined, the administration, which is still struggling with staffing issues, may dismiss the idea of safe zones altogether (see UNITED STATES: Trump will undercut McMaster at NSC - February 22, 2017).

_350.jpg)