Muslim Brotherhood will survive the Middle East crisis

Emirati demands for Qatar to cease financing the Muslim Brotherhood are in tension with the movement’s diversity

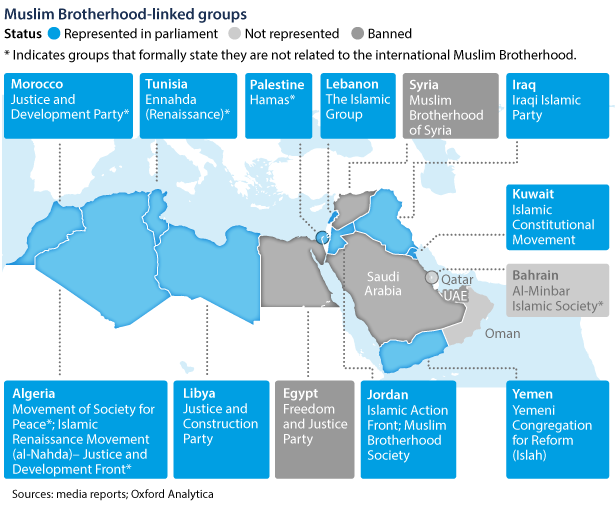

Doha’s support, whether tacit or active, for Islamist groups in the Middle East, particularly the Muslim Brotherhood, alienated it from some Arab neighbours. The recent boycott by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Egypt is party driven by their own problems with local Brotherhood affiliates that were linked to the broader political reform movement during the 2011 Arab uprisings.

What next

International attention on the Muslim Brotherhood because of the Gulf crisis will encourage national branches to focus ever more narrowly on their specific domestic environments. More local affiliates may renounce ties to the transnational movement; however, this will not translate into ideological change. The Brotherhood’s conservative social policies and support for popular participation in government will maintain traction in many Middle Eastern states.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Brotherhood affiliates will be significant military players in conflict-torn Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen.

- In parliamentary systems, cooperation with secular opposition will be increasingly important to countering international terrorism charges.

- The Muslim Brotherhood’s transnational links will become more personal and less institutional.

Analysis

The current Gulf crisis, which pits Qatar against Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt, is an unusually intense manifestation of a long-term clash. A key demand of the four states was that Doha should ending all ties with "terrorist, sectarian and ideological organisations" -- a veiled reference to the Muslim Brotherhood (see QATAR: Arab enemies may impose new sanctions - June 26, 2017).

Qatar's backing of Islamist groups during the post-2011 Arab uprisings, through funding, asylum policy and the media outlet of Al Jazeera, set it against its Gulf neighbours. They feared the Muslim Brotherhood, seeing it as a radical transnational movement that could take power elsewhere as it had in Egypt.

Brotherhood origins

Founded in 1928 by Hasan al-Banna, the Society of Muslim Brothers was initially conceived of as a social movement seeking to re-Islamise Egypt (see EGYPT: Repression may lead to new Brotherhood offshoot - April 26, 2017). Its early activities focused on grassroots conversions, and its bylaws prohibited direct political action until 1934.

However, the Brotherhood's ideology was inherently political. In al-Banna's conception, the state was instrumental to the re-Islamisation of society, based on three core principles:

- the Quran is the constitution;

- the government operates based on consultation (shura) with society; and

- the executive, like the people, is bound by the rules of Islam.

The original conception was that the Brotherhood should come to power politically only after society had been Islamised. The notion of 'slow Islamisation' was compatible with democracy, as members of a truly Islamic society would support Islamic rulers in elections.

Participation in elections has both assisted and altered the Brotherhood

As the ideology spread, the Brotherhood branches springing up throughout the Middle East therefore engaged in parliamentary elections. However, as they have become increasingly involved in local campaigns and answerable to domestic constituents, these groups' transnational ties have receded. Many are focused less on forming an Islamic state and more on nationally-specific, immediate demands for political reform.

Local variations

This diversification complicates the political context for the demands made of Qatar.

Largely because the Muslim Brotherhood's platform is so wide-ranging, with only broad outlines for proper governance and vague long-term goals, the organisation has become popular in a variety of cultural and political contexts. Its multiple 'franchises' operate very differently from each other, depending on local conditions.

While the international Muslim Brotherhood is often referenced as a single, monolithic bloc, it is in fact quite weak. Local affiliates are still linked by their ideological commitment to Islamic governance, but this is vague enough to allow a variety of interpretations depending on national circumstances and domestic politics.

The Brotherhood's transnational links are increasingly personal, not structured

The various national branches have few institutional connections -- although personal relationships between members can still be important. Further, several former branches -- for example, in Morocco and Tunisia -- have disavowed any ties to the transnational movement (see TUNISIA: Ennahda split will free the party's politics - May 20, 2016). Palestinian Hamas has successfully rewritten its charter without any mention of the founding movement, thus facilitating a rapprochement with its former staunch enemy, Cairo (see PALESTINIANS: Hamas and Fatah may mend rift - May 3, 2017).

Overall, this brand of Islamism has been effectively nationalised. Consequently, designating the Muslim Brotherhood in general a terrorist organisation, as Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt have done, is problematic.

Gulf crisis impact

The perceived transnational nature of the Muslim Brotherhood has opened both it and its backers such as Qatar to charges of meddling in other states' affairs. The latest crisis will therefore encourage local branches in their existing trajectory of focusing on their distinctive national environments.

The Muslim Brotherhood's already-fractious international network is likely to hold fewer formal meetings, as a means of protecting members from accusations of harbouring transnational goals. At occasional gatherings of the international Brotherhood, members will primarily share stories, rather than planning or coordinating their political agendas.

The 'Muslim Brotherhood' brand may suffer in the short-to-medium term as a result of the Gulf crisis. However, its ideology will not, given its broad popularity, with Brotherhood members elected to parliament in most Middle Eastern states. Local groups are likely to remain committed to the goal of Islamising society, as even the president of Bahrain's Muslim Brotherhood emphasised when he tried to distance his organisation from the central movement.

The case of Bahrain highlights potential divisions between Qatar's detractors on the Brotherhood issue. The Sunni ruling family in Manama struggling to control a majority-Shia population will not outlaw its Sunni Brotherhood affiliate as long as it maintains loyalty to the king and denies any international ties.

By contrast, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, which have banned the Brotherhood outright, will play up its links with terrorism. This will also give them a wider remit to shut down other domestically powerful Islamist movements.

Parliamentary politics

Other states in which openly Brotherhood-linked groups participate in parliamentary elections -- including Algeria, Libya, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Kuwait -- will probably continue to afford them that freedom, provided that they do not contest a plurality of seats in parliament or integrate too closely with other political opposition elements.

These parliamentary Muslim Brotherhood groups are increasingly likely, given the international political climate, to work closely with secular political reform movements -- as Ennahda did in Tunisia. They may prioritise pressing for greater political participation, instead of their traditional agendas focused on the broader Islamisation of society (see TUNISIA: Unions could hamper new unity government - June 23, 2016).

Another successful example that may encourage others is Jordan's National Coalition for Reform, which brings together Islamist, tribal, nationalist, and Christian politicians. This grouping managed to win 15 seats in September's parliamentary polls, becoming the largest opposition bloc in parliament with 11.5% of the Lower House. It promotes a civic, secular approach to Jordan's economic, political, and social issues, rather than the traditional Islamist platform.

By joining with secular blocs, Muslim Brotherhood affiliates can gain votes and the trust of non-Islamist segments of society, who will increasingly come to see them as partners rather than viewing them with suspicion. The latest crisis increases the pressure on Brotherhood groups to engage in cross-ideological cooperation, as this provides them with political cover and makes them part of the broader opposition, rather than independent targets.

_350.jpg)