Public-private partnerships will expand in Gulf states

Fiscal constraints are driving the rush for better business legislation in the Gulf Arab countries

Abu Dhabi will on September 10 hold an introductory workshop for companies interested in a public-private partnership (PPP) scheme for refitting street lights across the emirate. Gulf governments are increasingly turning to PPPs to finance infrastructure and other projects in response to tight public finances. Most countries in the region have developed or are developing legal structures to manage PPPs, and the first round of projects have come to tender.

What next

With fiscal situations likely to remain constrained, usage of PPPs will expand steadily. This could ease Gulf governments’ capital expenditure demands. However, government agencies may struggle in the tendering of complex projects, leading to delays. Poorly scoped projects could also store up problems for the future.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The large number of PPP projects likely to come to market across the region might make it harder to secure financing for them all.

- Lower capital expenditure costs from successful PPPs could reduce Gulf states' bonds issuance.

- Foreign investors in long-term PPP projects will want reassurances on business environment stability in light of the Qatar boycott.

Analysis

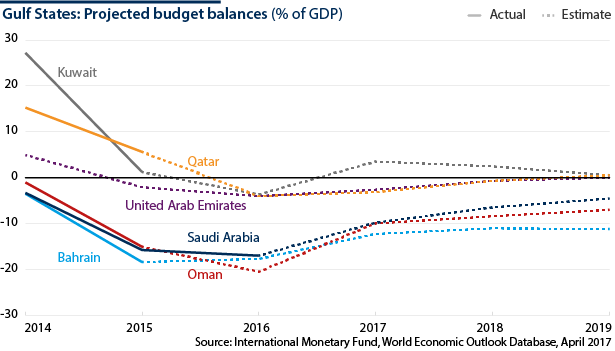

The collapse in oil prices that began in 2014 has pushed all of the Gulf Arab states into fiscal deficits, for the first time in over a decade in some cases (see GULF STATES: New taxes will not plug fiscal deficits - June 29, 2016). Elsewhere, existing deficits widened to double-digit levels.

These governments see PPPs as a tool to enable the continuation of infrastructure rollout plans in a more fiscally constrained environment (see GULF STATES: Privatisation will face obstacles - September 14, 2016).

Power PPPs established

The first PPP projects in the region were in the power and water desalination sector -- termed independent (water and) power plants, or I(W)PPs. These began in the mid-1990s when governments were also fiscally constrained by a previous bout of low oil prices and struggled to finance the large plants needed to meet growing demands.

In the last two decades, all six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states have utilised this model to varying degrees, including recently for solar power plants. The very first of the IPPs, Manah in Oman, is now nearing the end of its 25-year contract and is set to transfer to government ownership in 2020.

Pioneer power and water projects mostly succeeded

There is a broad consensus that the partnerships in the power sector have been effective. Projects were usually completed within their allocated time frame, kept up with the region's rapid demand growth and operated with few problems.

The fact that the model was utilised even in the Gulf's wealthiest states and during the height of the oil boom demonstrates that it was seen as delivering wider benefits than simply relieving pressure on state budgets.

This broad experience in the power sector has provided a model of how PPPs can deliver high-quality infrastructure. However, there have also been frustrations in some cases, such as the long procurement delays for power plants such as Al-Zour North in Kuwait, resulting from bureaucratic shortcomings and political obstacles.

Legislation developed

Most countries in the region have legislation governing I(W)PPs, but Kuwait was the first to develop a broader PPP law in 2008 and to create a dedicated agency, the Partnerships Technical Bureau (PTB), to manage PPP tenders.

However, shortcomings in the law and the agency, together with an obstructionist political environment, meant that it only awarded one contract. This led to revised legislation in 2014 and the formation of a new body with greater authority, the Kuwait Authority for Partnership Projects (KAPP), which replaced PTB in 2015, together with a new structure to encourage foreign investment.

Dubai's law seems a more effective model than Kuwait's

Most other Gulf states are following Kuwait's lead, albeit at differing paces and with laws that vary considerably in their terms. Dubai passed a PPP law that, unlike Kuwait's, does not require investors to make an initial public offering of shares in the project company.

The Dubai law came into force in November 2015 and the emirate has invited its first tenders. At a federal level, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is also considering a PPP law or looser framework based on the Dubai model.

Countries without a PPP law now realise that this puts them at a disadvantage, and are moving towards legislation:

- Qatar and Oman have both drafted PPP laws due to be enacted before the end of 2017.

- Saudi Arabia has begun tendering PPP projects under its existing procurement law but is considering dedicated legislation to facilitate the process.

- Bahrain began developing a PPP law in 2014, although there is no information on its current status.

Projects tendered

A handful of PPP-style projects were awarded even during the years of high oil prices. Examples were the Al-Wathba wastewater plant in Abu Dhabi in 2008 and Medina airport in Saudi Arabia in 2012.

In the new fiscal context,there has been a big uptick in the number of projects being considered for PPPs. These stretch beyond further power and water projects into a range of sectors:

- Open tenders in Kuwait cover railways, hospitals, schools and residential accommodation.

- In Dubai, the focus has been on transport, with a large car-park awarded in 2016 and a tender underway for Union Oasis station, a metro hub.

- Qatar's expected tenders include a World Cup football stadium and hospitals: so far, these seem not to be fundamentally affected by boycott, although there may be less competition among investors concerned about supply lines.

- Four more Saudi airports (in Taif, Yanbu, Hail and Al-Qassim) have been awarded as PPPs in 2017, with more expected to follow.

- Sultan Qaboos Medical City in Oman was structured as a PPP in 2016; further projects are planned in the transport, health and education sectors.

Investors are showing some enthusiasm; more than 100 firms expressed interest in a proposed Bahrain-Saudi causeway PPP tender.

Challenges

Nevertheless, the difficulties Kuwait has faced -- awarding just one PPP project, and none outside of the power sector, after nearly a decade -- are instructive. Kuwait's political system presents unique challenges, but other Gulf states may also struggle to formulate appropriate incentives and protections for investors or to implement transparent tender processes.

There is a general positive trend in all these areas. The World Bank in its latest Doing Business report noted reforms in Saudi Arabia and the UAE protecting minority investors. Nevertheless, across the region, developing adequate in-house expertise on PPPs could be a problem, with over-reliance on consultants for each project.

Further down the road, there is a danger that, while PPPs may reduce the state's short-term capital expenditure, they could increase the long-term costs for the state and service users. A key assumption justifying PPPs is that privately implemented projects are more economically efficient. Whether or not this proves true will depend heavily on how the regulatory and competitive environment is structured.

If the PPPs are effective monopolies, then there may be little incentive to bring down costs for the users and government, or to improve quality. Equally, government entities may not make a smooth transition from operator to regulator -- functions that require different structures and skills.