Abe will have little opposition to constitution reform

Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe yesterday won his fifth national election in succession

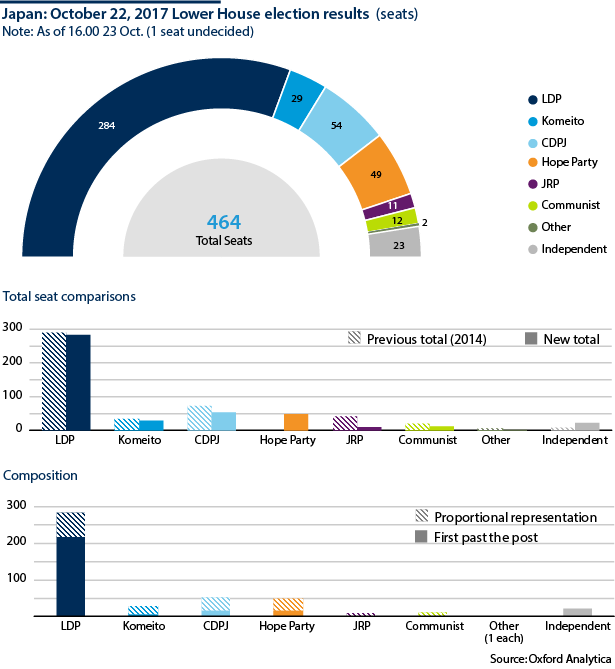

The ruling coalition led by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe yesterday won 67% of seats in the 465-seat lower house of parliament. Abe now seems securely positioned to become post-War Japan's longest-serving prime minister.

What next

Abe is unlikely to do more than allow his policies to develop on existing lines, without significant innovation. Meanwhile, the prospects for any influential opposition to the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) are remote.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Abe will make a vigorous push for a referendum on Constitution revision and has the numbers to succeed.

- The new Hope Party's numbers and influence are likely to decrease.

- A more coherent centre-left main opposition party may eventually emerge.

Analysis

Abe need not have called an election until late 2018. He did so for several reasons.

Firstly, the economic news has been positive: two quarters of strong GDP growth; record levels of employment; and particularly promising prospects for university and high school graduates. This matters given Abe's emphasis on Abenomics over the last five years, and that 18 and 19 year-olds were voting for the first time after a change in voting age.

Secondly, Abe argued that he would be stronger diplomatically vis-a-vis the threat from North Korea if he had popular democratic endorsement for his policies.

Thirdly, the opposition parties were in disarray.

However, the reason Abe gave for calling the election was that he wanted voter approval for his decision to use the revenue raised by an already scheduled increase in the sales tax in 2019 not to address public debt but to make pre-school and high school education free of charge and to fund better social care for the elderly.

Calling an early election gave the opposition little time to organise

Koike triggers turmoil

No sooner had Abe announced his intention to dissolve parliament, and before the ten-day campaign proper began, Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike announced she would launch a national counterpart of Tokyo First, the party she had created to fight the Tokyo metropolitan assembly elections in June this year. This had been a great success, winning votes and seats from both the ruling LDP and the main opposition Democratic Party (DP) (see JAPAN: Tokyo election setback weakens Abe's leadership - July 5, 2017).

Her new party was called Kibo no To (the Hope Party). A week later it revealed a wide range of policies including a poorly defined 'Yurinomics' and 'Twelve Nos', which included eliminating passive smoking, nuclear energy and hay fever.

The DP did so badly in the Tokyo assembly elections that its leader resigned and her place was taken by Seiji Maehara (see JAPAN: New opposition leader faces a losing battle - September 13, 2017). His unexpected response to Koike's announcement was to suggest that his party's legislators join Hope, which amounted to dissolving his party.

Some members immediately sought to stand as Hope candidates, staying in the same constituency and changing only their party label. However, Koike admitted only those who supported the security policy reforms Abe passed in 2015 (see JAPAN: Defence legislation realises Abe's goals - June 11, 2015). Others, including many of those who had served in leadership posts, such as Yoshihiko Noda (prime minister 2010-12), chose to stand as independent candidates.

Meanwhile Yukio Edano, who had run unsuccessfully for party leader, quickly organised a new Constitutional Democratic Party (CDPJ), formally registered it as a party and gathered 75 candidates, most of whom had been on the progressive wing of the DP.

Before the campaign proper began, the media speculated about whether Koike would stand for a parliamentary seat and what her party's policies would be. The theatrical elements of this enabled the party to make an impact on early opinion polling. However, Koike refused to stand and would not clarify who she would support to be prime minister if the LDP won so few seats that Abe felt forced to resign. Media interest waned.

The hastily organised CDPJ negotiated agreements with the Social Democrats and Japan Communist Party not to run against each other and Edano resolved not put up candidates against Hope candidates who came from the DP.

Campaign platforms

Probably remembering that voters do not like to be reminded about tax increases, Abe's proposals about how he would spend the sales tax after 2019 got little or no mention.

Abe instead emphasised the need for endorsement of his diplomatic strategy towards North Korea. He talked up Abenomics, claiming responsibility for rises in GDP and employment. He stressed the need to make education free. However, he said little about Constitution revision, an issue close to his heart but not one that most voters find interesting.

Koike and the Hope Party concentrated on being the anti-Abe party -- opposing the sales tax increase and Abe's alleged cronyism (see JAPAN: New rival threatens Abe in snap election - September 27, 2017). They, too, said little about Constitution reform although they do not oppose it. They made much of their pledge to eliminate nuclear power at first, but this issue faded as the campaign progressed.

Komeito emphasised its credentials as the party that had ensured stability for two decades as a reliable ally of the ruling party. It supported making education free but stayed well clear of Constitution revision, which is unpopular with its supporters.

Five years ago, the Japan Restoration Party looked as though it was about to break through from its Osaka base and emerge as a national 'third force'. Its agreement with Koike not to compete for seats in Tokyo was rational but reinforced its image as a regional party. Its main message was that high school education is already free in Osaka, made possible by careful use of local budgets. It encouraged the rest of the country to emulate this.

The CDPJ opposed the sales tax increase and made a case for grassroots democracy and respect for the existing Constitution.

Finally, the Communist Party opposed Constitution reform, sales tax increases and the re-start of any nuclear power plants.

Outlook

Abe is confirmed in power and will probably get a third three-year term as party leader when his current term expires next September.

There was no indication in his campaign speeches that he will deviate from the policies he has espoused over the last five years.

The LDP-Komeito ruling coalition has the two-thirds majority it needs to pass a proposal to revise the Constitution. The Komeito is unenthusiastic, but this matters less now that the LDP can rely on the support of the Restoration and Hope parties. A serious attempt will be made to revise the Constitution before the next lower house election. Well over 370 members of the 465-seat lower house favour doing so.

The CDPJ won enough seats (barely) to become the largest opposition party. This number will grow as those who stood as independents and maybe some who joined Hope move back, assuming they are admitted.

The Hope Party will have no leader in parliament who has the authority or charisma of Koike

The Hope Party's durability is questionable. Its policies and centre-right ideology, when stripped of the anti-Abe elements, differ little from the LDP's. As the campaign fades in their memories, legislators will wonder what they can do to ensure re-election; other parties may offer more security.

Over the next five to ten years, the CDPJ could develop into a centre-left party more coherent than either the DP or its predecessor that is able to rival and replace the LDP. For the next three to four years, however, Abe and the LDP are unlikely to face coherent, constructive opposition.