Saudi purge will quell critics but worry investors

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman's mass arrests may mean more transparency; certainly more autocracy

The attorney-general yesterday stated over 200 people had been questioned after targeting an alleged 100 billion dollars in misappropriated assets. This follows unprecedented arrests of senior princes, ministers and businesspeople in an anti-corruption purge beginning on November 4. The move has alarmed many in the ruling family and business elite, who had enjoyed relative impunity. However, it is so far broadly popular among a youthful Saudi population, who blame high-level corruption for economic problems and unemployment.

What next

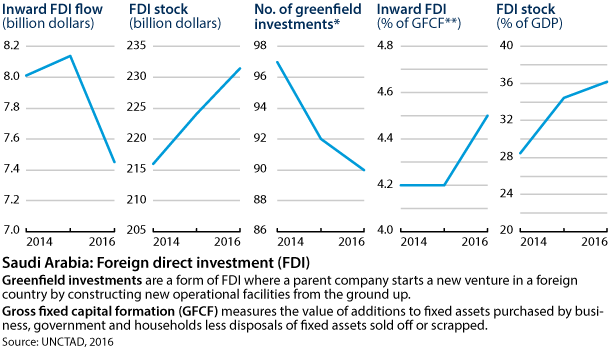

Critics of Mohammed bin Salman will increasingly be deterred from speaking out, let alone organising against him. Clamping down on corruption in theory could help strengthen the economy. However, as recent moves by the crown prince have increased both regional and domestic risks, it will be difficult for him to reassure investors.

Subsidiary Impacts

- A slowdown in investment will make it even harder to meet the economic targets of Vision 2030 and launch the ambitious NEOM project.

- The combined strengthening and politicisation of anti-corruption mechanisms will complicate performing due diligence about Saudi partners.

- Opposition within the royal family is likely to be strong but muted in the short term, with an atmosphere of febrile rumour.

Analysis

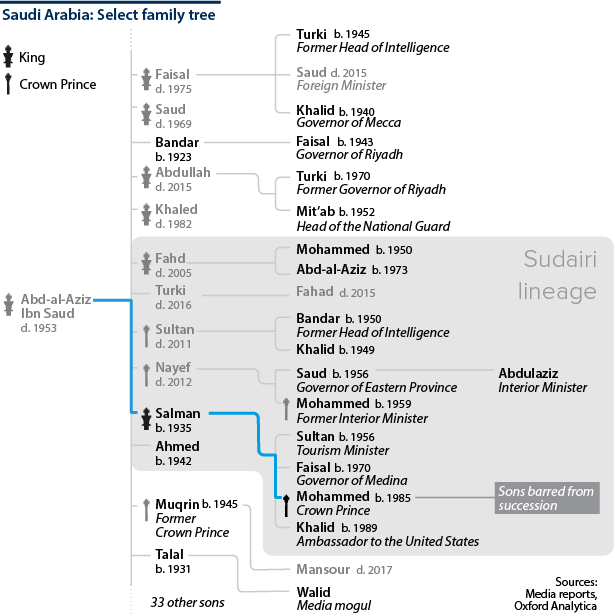

Since the wave of high-profile arrests, more than 1,700 bank accounts have been frozen (see SAUDI ARABIA: Power centralisation risks backlash - November 6, 2017). These reportedly now include the accounts of the former crown prince and interior minister, Mohammed bin Nayef, who was deposed in June.

Rumours of other arrests are flying as the clampdown widens, underlined by the reported cordoning-off of another five-star hotel next to the Ritz Carlton in Riyadh, where arrested dignitaries are held. It is possible that several younger-generation princes once seen as contenders for the throne will be not only disempowered, but jailed -- unprecedented for the traditional Gulf monarchy.

Business implications

To reassure stock markets, the central bank has clarified that only individual rather than corporate assets would be frozen -- although it may not always be clear where the lines are drawn. The labyrinthine judicial system has long worried foreign investors, and companies that previously thought themselves well-connected will be trying to calculate a new set of political risks to local business partners.

Some Saudis express optimism that the alleged 100 billion dollars that have been misappropriated can be returned to the public purse -- which would be significant, equating to about one-quarter of the annual budget. However, this is likely to prove problematic: there are reports of capital flight.

Businesses elsewhere in the Gulf with Saudi connections could be caught up in the investigation

Given the extent of business connections across the Gulf Arab states, a key factor will be how far Riyadh's neighbours cooperate. The United Arab Emirates has already said it will freeze related bank accounts, raising the prospect of a wider impact on business families across the region.

Princely calculations

Mohammed bin Salman has developed a modus operandi of making sudden, unexpected moves to signal that Saudi Arabia's old ways are changing. This was seen in his other initiatives: the war in Yemen, the Qatar embargo and the more recent announcements on women driving and a return to 'moderate' Islam.

The anti-corruption drive has several benefits for the crown prince.

- Under austerity, Saudi Arabia genuinely needs to rein in the royal-family diversion of funds that was tolerated in a wealthier era.

- It provides him with cover to remove sons and allies of former kings and crown princes from power.

- The choice of arrests will help him consolidate his power over both internal security and the media.

The move to a populist authoritarian model is a complete turnaround for Riyadh

Essentially, the crown prince has decided to push for systemic change. The wide patronage network of traditional elites -- royals, clerics and merchants -- that sustained but also constrained the power of Saudi kings for decades is arguably no longer manageable with reduced oil revenue. However, the apparent new model for political stability, based on direct populist engagement with a predominantly young and often middle-class support base, is completely untried in this environment.

It was already clear that Mohammed bin Salman put little stock in the traditional business elite, courting popularity by cutting payments owed to contractors when faced with a fiscal crunch, rather than moderating public-sector pay. In 2016, the government withheld funds from giants such as the Bin Ladin Group, whose head has now been arrested, and Saudi Oger -- the family firm of Saad al-Hariri, who resigned as prime minister of Lebanon on the day of the purge and remains in Riyadh under dubious circumstances (see LEBANON: Deeper Iran-Saudi conflict will hurt Beirut - November 8, 2017).

New economic model?

The vested interests of the Saudi business elite in the existing system of oil-fuelled government spending and cheap imported labour mean they have often acted as a brake on economic reforms. Young entrepreneurs see them as an obstacle to new entrants and start-ups.

In a new climate of fear and uncertainty, investors are trying to work out how far these arrests -- many of people long reputed flagrantly corrupt -- will lead to a new and more transparent style of doing business. It is still unclear whether this will prove a rejection of cronyism or merely a changing of the cronies.

With Mohammed bin Salman himself, rather than an apolitical figure, presiding over the new anti-corruption body, there will be concerns that his inner circle may not face similar scrutiny. Even the arrest of Adel Faqih, the minister of economy and planning and a member of that inner circle, raises more questions than it answers.

Faqih was mayor of Jeddah during the 2009 floods, which killed around 100 people after it was revealed money earmarked for sewers and drains had disappeared, leaving manhole covers with nothing beneath them. However, presumably the crown prince did not perceive Faqih's role as problematic when he appointed him minister in April 2015.

It is possible the two men differed over economic strategy: Faqih's ministry has been revising the immediate targets for the crown prince's hallmark Vision 2030, which were supposed to be published at the end of October (see SAUDI ARABIA: Privatisation will privilege the state - July 10, 2017).

Public reactions

The tribally founded National Guard will deeply resent the arrest of its head, Mit'ab bin Abdullah, given its longstanding loyalty to his family branch. A 'counter-coup' against Mohammed bin Salman seems unlikely in the short term, given the lack of public space for dissent. However, unhappy security forces are at greater risk of infiltration -- for example, by salafi-jihadists.

Much of the wider public may initially react with optimism. Corruption, patronage and nepotism have helped bind the elite together but have alienated those on the outside and contributed to a sense that study and hard work are not rewarded. However, there are greater risks in the medium term.

Mohammed bin Salman is little different from other princes in his preferences for luxury living and conspicuous consumption, and like all royals depends in part on the state to sustain this: any new corruption scandals that might emerge around him or his close associates would now be all the more damaging.

Moreover, if (as seems likely) cautious investors now hold back, disappointed high expectations of economic transformation could provoke a medium-term popular backlash -- and the royal family's traditional pillars of support will no longer be there.

_350.jpg)