Four disintegration risks may threaten the EU’s future

The EU developed a renewed sense of optimism over the past year, but new crises may loom

After the French presidential election, which saw the decisive victory of Emmanuel Macron over National Front leader Marine Le Pen, a sigh of relief could be heard in European capitals: the worse had been avoided; the EU would thrive again. This relief could be premature. At least four disintegration risks are still threatening the EU.

What next

Calls by European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker and Macron for a more united EU by the mid-2020s appear complacent, as they fail to acknowledge the risks of disintegration. As for the elusive idea of reforming the euro-area, competing projects promoted by France and Germany could end up cancelling each other out so that a dangerous status quo prevails, preparing the ground for another European crisis in a near future.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Even though its economic prospects are positive, the euro-area remains fragile and could plunge back into chaos if left unreformed.

- An economic downturn would benefit Eurosceptic populist parties.

- The political uncertainty of a caretaker government in Germany will increase its officials' reluctance to agree to any euro-area reforms.

Analysis

The EU faces at least four risks of disintegration, ranked in ascending order of danger to the project of European integration.

Europe's first contraction

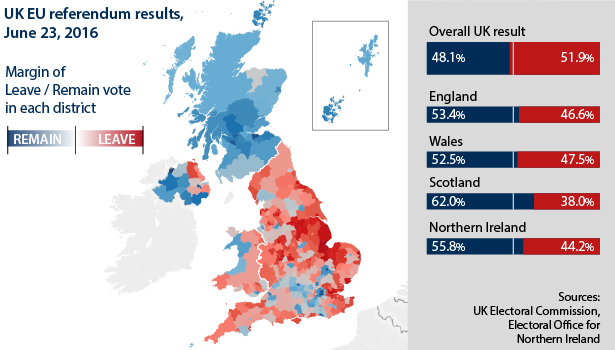

After 60 years of enlargement, the EU will face its first contraction when the United Kingdom leaves the bloc on March 29, 2019.

For the EU, this means the loss of a global financial hub and one of its leading military powers. The Brexit vote also raised fears that Eurosceptic movements in countries such as the Netherlands or France could be boosted.

However, this form of disintegration may be the least dangerous for the EU in the long term, as it provides member states with an opportunity to rethink the terms of their alliance. Moreover, the political turmoil in the United Kingdom since the Brexit vote and signs of economic damage have dampened Eurosceptic parties' appetite for referendums on EU or euro-area membership in their own countries (see PROSPECTS 2018: United Kingdom - November 17, 2017).

Euro-area's vulnerability

The critical intervention of the ECB in July 2012 to protect the euro and the chaotic but eventually stabilising summer of 2015 (when Greece almost left the euro-area) helped avoid an even worse economic and financial crisis, but very little has actually changed in euro-area governance since 2008.

In his speech on September 26, President Macron cautiously retreated from his proposal to create the position of a finance minister for the euro-area, but he is still pushing for a European autonomous budget. The European Commission, which will lay out its own vision on December 6, is still calling for an economy and finance minister, but it is unclear what powers such a minister would have in practice.

Whatever the nature of the government that eventually emerges in Germany, it is unlikely that it will accept a euro-area finance minister or the creation of a euro-area budget, at least if this amounts to more than merely symbolic measures with little impact in practice.

Chancellor Angela Merkel supports the idea of converting the European Stability Mechanism into a 'European Monetary Fund'. This idea, proposed by then-Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble -- not exactly a supporter of financial solidarity within the euro-area -- would reinforce fiscal discipline among member states but would be unlikely to create a culture of cooperation.

The economic divergence between euro-area countries remains unaddressed

The positive economic performance of the euro-area indicates that the region is finally exiting the 'great recession' that started with the financial crisis a decade ago (see PROSPECTS 2018: Euro-area - November 8, 2017).

However, the main problem in the past has not been the (potentially misleading) average performance of EU and euro-area member states, but rather the divergence between them -- and this remains unaddressed.

Fractured community of citizens

"The wind" might be "back in Europe's sails" as Juncker said in his State of the Union speech in September, but EU citizens are still not back on board (see EU: Commission will seek to drive integration again - September 14, 2017).

The Eurobarometer survey of autumn 2016 (published last December) indicates that confidence in the EU has fallen to 36%, almost 15 percentage points below the 2004 level. According to Eurostat data, confidence in European institutions fell from 53% in 2000 to 42% in 2014.

It was in 2011 that a majority of citizens began to turn away from the EU, as member states proved incapable of proposing a coordinated and effective strategy to emerge from the economic crisis and boost growth. Confidence in the EU is lower in the euro-area than in the non-euro countries and it is particularly low in the three major signatories of the treaty that established the European Economic Community -- Germany, France and Italy -- where it fails to rise above 30%.

This discontent has translated into the rise of far-right and far-left populist parties across the continent. The relief brought by the defeat of Le Pen has been clouded by the Alternative for Germany winning 94 seats in the general election in September.

20%

Share of Europeans voting for a populist party

Data from the TIMBRO Authoritarian Populism Index 2017 points to a wider trend: on average, 20% of Europeans vote for a populist party, a share that has roughly doubled since the early 2000s. In absolute numbers, 55 million Europeans voted for a populist party in the latest rounds of general elections.

Double secession in EU

The success of the single market has been paradoxical: it brought countries closer together but led to an increasing divergence between regions (and more generally, between local jurisdictions or territories). Across the EU, the gap in economic development between regions is larger than the gap between countries (see EU: Innovation disparities will be hard to overcome - October 20, 2017).

The single market brought countries closer together but increased the divergence between regions

This geographical division within EU member states, which is also found in countries outside Europe but which the single market has undoubtedly accentuated by the powerful agglomeration effects it generates, has two perilous consequences for the unity of nation states: it fosters the temptation for rich regions to secede, and segregates and polarises the electorate.

While Catalonia may not succeed in its attempt to become independent from Spain, its struggle highlights how the combined issues of cultural identity and economic separatism can fracture the EU.

The degree of polarisation is illustrated by maps of votes in recent elections or referendums in the United Kingdom, France and Germany, that show clear geographical segregation (see GERMANY: East-West divide will persist - December 22, 2016).