Gulf monarchies may update power structures

Ruling families are gradually changing the traditional rules of succession and decision-making

While most systems in the states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) vaguely follow patrilineal primogeniture, irregularities have occurred in each case, complicating claims of rightful leadership and making patterns less predictable. With younger generations coming to the fore in Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in particular, questions of lawful succession are becoming more relevant.

What next

There will be efforts at consolidation throughout the Gulf, with the rise of the Salman branch of the Saudi ruling family and related trends in Kuwait and Bahrain. New generations will likely adopt a style of ruling that favours faster decision-making over their predecessors’ caution. Nationalism in the Gulf states will become ever more focused on prominent figures in ruling families, rather than on the states themselves, and will intensify even in the face of new austerity measures.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Democratic reforms are unlikely, even more so thanks to US withdrawal from Gulf domestic concerns.

- Participation in government will be filtered through state institutions, rather than emerging independently.

- Foreign investment could be damaged by political uncertainty over succession issues and upcoming generational changes in Kuwait and Oman.

Analysis

The GCC monarchies, despite their reputation for stability, are in fact remarkable for the variety and mutability of their rules of succession; and their relatively recent pasts of political crisis.

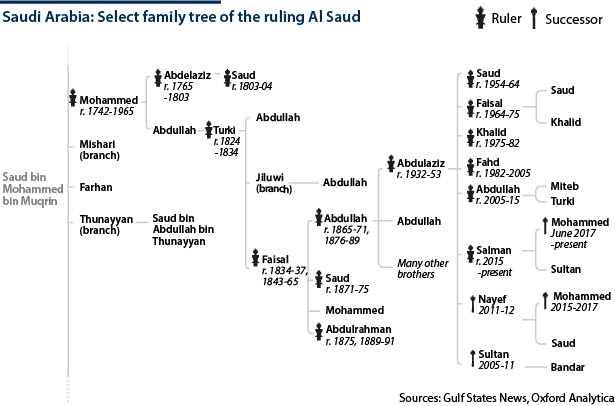

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is known for its seniority succession of brothers, yet this was only established after conflict. King Abdulaziz al-Saud, the founder of modern-day Saudi Arabia, appointed as heir his eldest son, Saud, who when he came to power in 1953 elevated his inexperienced sons rather than more qualified uncles and nephews.

The family in turn backed his brother Faisal to remove Saud in 1964, thereby establishing the norm of seniority succession rather than primogeniture. Because the ruling family is as large as 5,000 members, the line of succession had to be narrowed.

In 1992, King Fahd introduced the Basic Law, which opened future succession not just to sons of Abdulaziz, but to their descendants; it stated that "the most upright" should be preferred, thus removing seniority (at least in theory) as the primary consideration. The Basic Law also allows the king to choose his heir.

However, in 2007 King Abdullah aimed to resolve family tensions by establishing the Allegiance Council to name the heir apparent. After the 2011 death of Crown Prince Sultan, the council (35 senior ruling family members secretly selected by the king and the most powerful princes) operated as intended, choosing Prince Nayef as the new crown prince.

By contrast, subsequent appointments -- most recently the elevation of King Salman's son Mohammed bin Salman as crown prince in June 2017 -- have only been ratified in retrospect by the council, reflecting a centralisation of power (see SAUDI ARABIA: Royals will back the new crown prince - June 27, 2017). This latest appointment also constitutes the long-awaited shift to the next generation.

The Salman branch could control power for decades -- or longer

When Salman dies, the council is unlikely to have any influence over the succession of his son; the many family members losing out under the new regime would therefore have to work outside the formal system to oppose him -- currently an unlikely scenario (see SAUDI ARABIA: Power centralisation risks backlash - November 6, 2017). Mohammed bin Salman's nomination was accompanied by a declaration that the kingship would go to a different family branch next time, not to his own sons or brothers -- but after several decades of his rule, that might change.

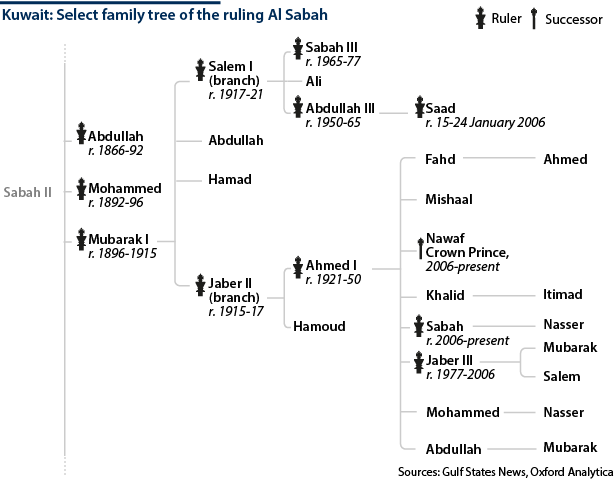

Kuwait

Another system without primogeniture is Kuwait, where through most of the 20th century the position of emir peacefully alternated between the Al Jaber and Al Salem branches of the ruling Al Sabah family. This was temporarily disrupted in 1965, when Sabah Al Salem succeeded his brother, but was restored in 1977.

In the later years of Emir Jaber, however, some of the problems of a seniority system, whereby older but not necessarily more experienced members of the family come to power, became more obvious. The offices of prime minister and crown prince were divided in 2003 to address this by diluting the power of the hereditary ruler.

After Jaber's death in 2006, the succession was more fundamentally disrupted, as heir apparent Saad al-Abdullah (an Al Salem) was physically unable to take the oath of office. For the first time, parliament, the most powerful legislature in the GCC, intervened in the succession, selecting then-Prime Minister Sabah al-Ahmad (an Al Jaber) as emir.

The Jaber branch has likely taken long-term control in Kuwait

Again breaking with the tradition of alternation, Emir Sabah appointed members of his own Jaber branch as crown prince and prime minister. A lack of qualified members of the Al Salem line suggests there will be no return to alternation: senior Al Jaber are already manoeuvring over the uncertain succession after 79-year-old, low-profile Crown Prince Nawaf.

The trend towards consolidation into a single branch of the ruling family mirrors that seen in Saudi Arabia. However, it is too early to identify a movement towards primogeniture, despite the emir's promotion on December 11 of his own son, Nasser, as deputy premier (see KUWAIT: Succession squabbles may undermine government - December 12, 2017).

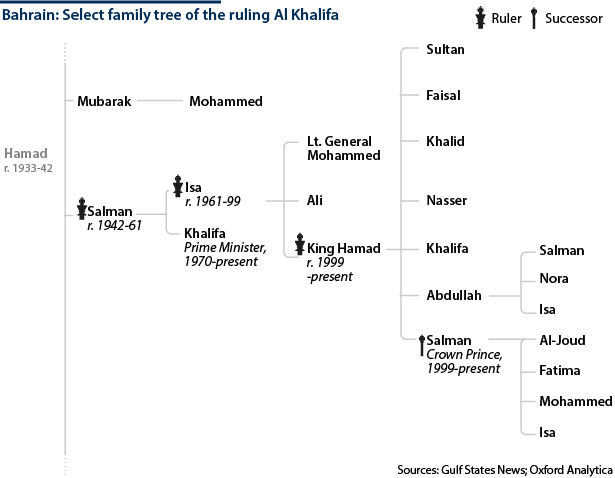

Bahrain

Indeed, Bahrain is the only GCC state to have consistently followed a pattern of primogeniture, with its fourth consecutive father-eldest son succession taking place in 1999. (The 1973 constitution, while referencing primogeniture, in fact allows the emir to appoint a younger son as crown prince during his lifetime.)

King Hamad's designation of his eldest son, Salman, as crown prince in 2002 further institutionalised the system of patrilineal primogeniture and centralised political capital -- especially after Salman was also named first deputy prime minister in 2013.

The alternative Al Khawalid branch of the family (descendants of Khalid bin Ali) also has significant power, backing a conservative political agenda. After the 2011 protests, their influence contributed to the victory of the emir's brother, Prime Minister Khalifa bin Salman, who supported a crackdown on the Shia demonstrators, while Crown Prince Salman's preference for dialogue was sidelined (see BAHRAIN: Deeper economic reforms will occur soon - July 27, 2016).

Ultimately, however, the dominant Al Khalifa family maintains its primacy in government. It appoints members as ministers, largely controls land ownership and leases (to the anger of the opposition) and handles internal disputes privately through a ruling family council. The system is broadly stable.

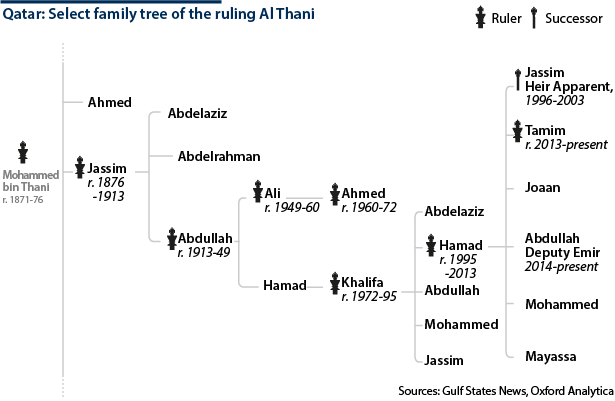

Qatar

There is also a surprising degree of regime stability in Qatar, despite its neighbours' efforts (see QATAR: Solution is unlikely at Gulf summit - December 4, 2017).

The last emir, Hamad bin Khalifa, changed the constitution to remove control of succession from a family council, centralising power in line with the wider Gulf trend. Previously, potential successors' efforts to gain the support of family members led to squabbles and multiple demands from segments of the notoriously fractious Al Thani family.

Despite this factionalism, succession (except when Emir Khalifa overthrew his cousin Ahmed in 1972) has usually passed by primogeniture. Nevertheless, out of the six latest successions, there have been two coups and three abdications, only one of which (Hamad handing power to his son, incumbent Emir Tamim, in 2013) was voluntary.

Because of these irregularities and internal Al Thani family rivalries, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, seeking to target Doha, are able to put forward alternate heirs. One example is Abdullah bin Ali, a brother of the deposed Emir Ahmed based in Saudi Arabia. This branch of the family, while not politically powerful, owns considerable land and assets.

Gulf rivals have presented Abdullah as the rightful ruler, with the backing of the exiled president of the Qatar National Democratic Party, Khalid al-Walid al-Hail, who in September led a London conference promoting the notion that Tamim lacks popular support and domestic legitimacy.

External efforts to depose the current emir have gained little traction

In reality, however, Tamim retains considerable political support, only bolstered by recent events; internally, the norms of Qatari succession are rarely questioned. Discontented family branches have too little domestic backing to pose a genuine threat to power.

Indeed, some local clans such as the Attiyah and Al Fardan are arguably more politically influential than segments of the Al Thani. Tamim has focused more on promoting technocrats than family members to ministerial positions. He has designated his half-brother Abdullah as deputy ruler but not yet named an heir; as his children are still young, this suggests the intention of continued primogeniture.

UAE

Due to the UAE's unique federal system of seven distinct emirates with six ruling families, succession has not been as central an issue nationally as elsewhere in the GCC: each emirate makes its own rules. The succession of the federal president (also historically the ruler of Abu Dhabi, while the Dubai leader is vice-president), is outlined in the constitution, promoting stability at the national level; but the norms within each emirate have not been codified and so vary widely.

Succession among the Al Nahyan of Abu Dhabi and Al Maktoum of Dubai has nevertheless remained largely stable, involving a mix of primogeniture and seniority succession among brothers, depending on the age and experience of prospective new leaders (see UNITED ARAB EMIRATES: Political stability is strong - July 12, 2016).

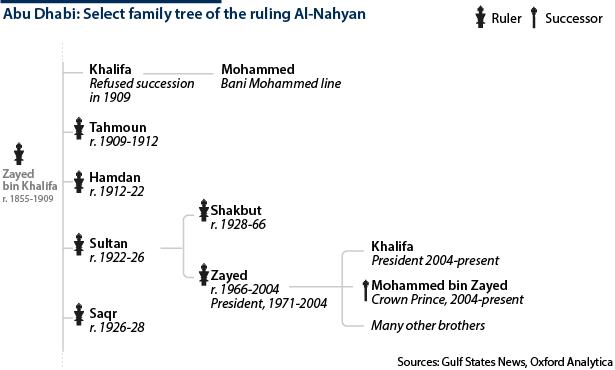

Abu Dhabi

Zayed, the ruler of Abu Dhabi until his death in 2004, orchestrated the succession of his son Khalifa under a secret family agreement reached in 1999, while his third son Mohammed became crown prince and therefore the next in line to the throne.

Mohammed bin Zayed is the powerful de facto ruler of the whole country. Potential rivals have generally been moved into other positions, particularly within the Federal National Council (FNC) and the oil and finance sectors.

Reports did emerge in 2015 of an attempted coup involving Zayed's fourth son Hamdan, among others, with the aim of establishing a constitutional monarchy. Although the details are unclear, Hamdan has since then not held any high-profile positions, so any potential threat seems to have been neutralised.

Dubai

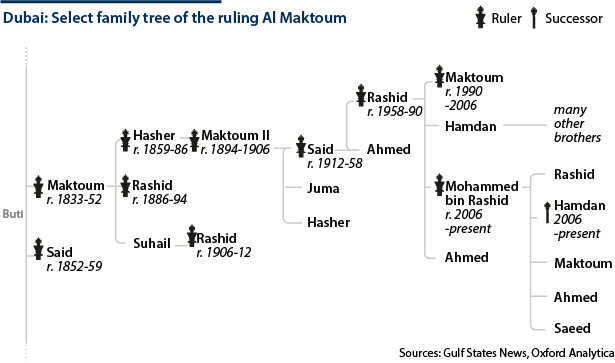

Dubai's Al Maktoum also tends towards peaceful succession. In 2006, Mohammed bin Rashid took over from his brother Maktoum, breaking the pattern of primogeniture in place since 1912.

Two years later, he replaced his older brother Hamdan bin Rashid with his own son Hamdan bin Mohammed as heir apparent, returning to the primogeniture model. Nonetheless, this could potentially lead to future disputes: Hamdan bin Rashid became finance minister and deputy ruler of Dubai, giving him a significant support base, particularly in the business community.

Oman

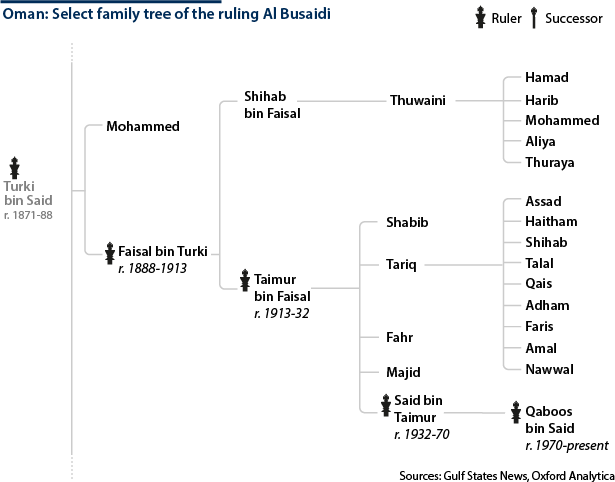

Finally, Oman, with one of the region's smallest ruling families, has the most mysterious system of succession (see OMAN: Sultan’s successor will face an economic crisis - May 16, 2017). Incumbent Sultan Qaboos has no children or brothers and has not named a successor, perhaps out of fear of being overthrown -- he himself in 1970 overthrew his father with the help of his uncle. The unbroken line of father-son succession dating back to 1871 will end at his death.

The 1996 Basic Law, amended in 2011, states that only male descendants of 19th-century Sultan Turki, with both parents Omani Muslims, are eligible to take the throne. Three of the sultan's cousins, Assad, Haitham and Shihab bin Tariq, are seen as the most likely successors; Taimur, the son of Assad, is also a contender.

The Ruling Family Council -- a body that may never actually have met -- is required to to choose a successor within three days of Qaboos's death. If it cannot agree, the Defence Council, together with the heads of the two legislative chambers and three Supreme Court members, will confirm the person named in a letter left by the former sultan.

There is ample potential for confusion and competition: Sultan Qaboos in 1997 noted that he had designated two potential heirs. He has also overseen an extreme centralisation of power, himself serving as army chief of staff, minister of defence and foreign affairs and central bank chairman; he has no prime minister. As a result, few members of the ruling family have much experience of government, which could complicate post-succession politics.

Ultimately, it is uncertain whether such personalised power can be maintained after the sultan's death. The likely alternative is a wider ruling family cabal, ahead of a more technocratic or bureaucratic transition.

_350.jpg)