Italy election is unlikely to yield a stable coalition

A parliamentary stalemate or an unstable majority for the centre-right are the most likely outcomes

The general election will take place on March 4. The electorate is deeply divided in ways that make compromise between parties extremely difficult. Unless the centre-right overcomes its divisions, another election seems likely very soon.

What next

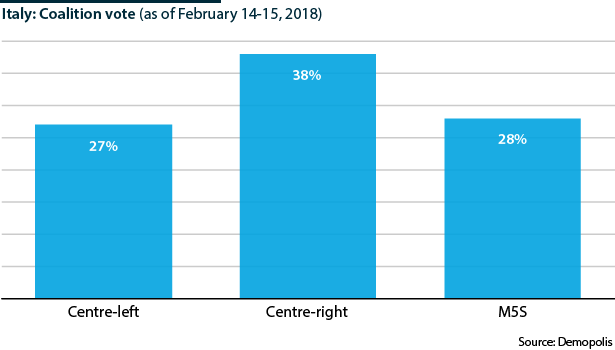

A majority for the centre-right alliance is possible and such a government might for some time be stable. If there is no such majority, the next moves will be difficult. With over 40% of the electorate expected to vote for anti-establishment parties, a continuation of the broad cross-party alliances of centre-left and centre-right that have governed since 2013 seems unlikely.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Electoral deadlock could alarm currency and bond markets.

- If the M5S and League become the largest parties overall and on the centre-right respectively, there will be a risk of market instability.

- Financial market risk will probably materialise if efforts to build a centre-right coalition fail.

- If there is deadlock but the PD and Forza Italia underwrite a caretaker, markets may react with equanimity (though voters will not).

Analysis

There have been few recent European elections where so many different outcomes are conceivable. There are uncertainties over the vote itself, coalition building, social cohesion and elite cohesion.

The vote

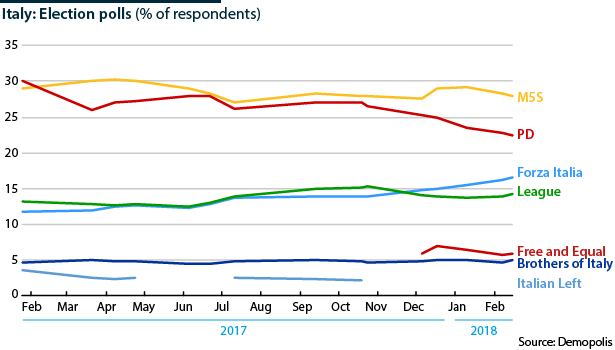

Polls have been fairly stable through the election campaign, though with a small but significant decline in predicted vote share for the governing centre-left Democratic Party (PD) and a rise for the centre-right alliance comprising former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia, the populist League (formerly the Northern League), the far-right Brothers of Italy and a small group of moderates (see ITALY: A new centre-right government could be weak - February 15, 2018).

The stability and consistency of the polls suggest they are reliable. One-third of voters are still unsure how they will vote. This segment -- if they do vote -- would need to be distributed proportionately across the parties for this factor not to affect poll reliability. It is impossible to know whether that will be the case.

Moreover, the normal margin of error (3 percentage points) means that even if the polls are accurate, individual parties could turn out to be stronger or weaker than predicted. With eight or nine parties likely to win seats in parliament, this could impact the feasibility of certain coalitions.

It is also unclear how tactical voting in single-seat contests (one-third of the total seats) will affect the parliamentary outcome.

Finally, the centre-right coalition is currently running at 35-37% of the vote. That is within sight of the 40% the coalition needs to win a bonus of seats and a workable majority, but the probability remains against it overcoming this hurdle.

Coalition uncertainties

Outside the centre-right, none of the main parties is likely to be able to form functioning coalitions with others.

Any coalition-building would be complicated by the fact that party identification among parliamentarians has become alarmingly weak in recent legislatures. The effects can be positive under certain circumstances -- it allowed enough defectors from the centre-right to ensure the survival of the largely centre-left governments of Prime Ministers Enrico Letta, Matteo Renzi and Paolo Gentiloni -- but are mostly negative.

The anti-establishment Five Star Movement (M5S), expected to emerge as the largest party with over one-quarter of the seats, has Eurosceptic roots in common with the League but has toned this down in recent months. While the M5S is anti-immigrant, it is not racist in the way the League is.

Any post-electoral effort to build a radical, Eurosceptic coalition around these two movements would therefore almost certainly lead to defections from left-leaning M5S lawmakers in parliament, even if such a coalition were arithmetically feasible at the outset.

It is very unlikely that the M5S will end up governing

Other ways in which the M5S could use its parliamentary strength look equally improbable. The M5S rejects a deal with the PD despite an overlap in the social bases of the two parties. Forza Italia certainly cannot work with it after Berlusconi said the movement's irresponsibility was the largest threat facing Italy (see ITALY: Di Maio may play a key role in next election - November 27, 2017).

The PD, which is likely to emerge as the second-largest single party, will not work with the League or the far right.

Its antipathy towards the left-inclined Free and Equal movement, despite their common origins not long ago, will weaken the centre-left as a whole in any bargaining with other parties.

This leaves few feasible options. The PD and the centre-right both feel they cannot risk another version of a grand coalition which could leave their own party bases dissatisfied and blur their identities for little electoral reward. It is possible that there will be no viable alternative, but populist opposition parties would quickly outbid such a coalition, risking further polarisation.

Social tensions

The election campaign has failed to throw up any new ideas on how to deal with pressing issues of poor economic growth, social inequality and the consequences of demographic change. Ultimately, the election may come to be seen as heightening rather than resolving serious social tensions.

The election campaign has failed to produce new ideas on how to address social tensions

The long recession has exacerbated the declining trend in birth rates among indigenous Italians. This is generating widespread concern given high rates of trans-Mediterranean migration and the perception of high birth rates among immigrants. Alarm about rising crime rates and personal insecurity, whether justified or not, has been a marked feature of the campaign.

For Italy to grow in a sustained way that addresses these tensions, structural reforms -- which are currently not being discussed by the parties -- would be needed. Their foundation depends, in the absence of major changes to the structure of the euro-area, on sustained budgetary discipline. This is beginning to look unviable across yet another legislature.

Elite cohesion on budgetary discipline

The immediate risk in the March 4 election is that no stable government emerges. Beyond that, and more seriously, there is a risk that elites are losing conviction that austerity is sustainable.

The only party advocating offering sustained budgetary discipline is the centre-left PD

The only party offering sustained budgetary discipline is the PD and even its proposals are poorly costed. Other parties are proposing solutions that are incompatible with the euro-area Stability and Growth Pact.

In the past, election programmes have been trimmed back by parties once in power in such a way that Italy has clung doggedly to a sustained primary fiscal surplus that has kept it just about credible in international bond markets. It may manage this again briefly in 2018 if deadlock generates a caretaker government, for which no individual party takes responsibility before the voters.

However, if global growth and higher inflation bring the start of a secular rise in interest rates in the coming year or two, the sustainability of budgetary discipline will be in doubt. A major increase in debt-servicing costs is one of the largest risks facing Italy; the debt-to-GDP ratio is above 130%. This could make anti-EU and anti-euro populism far harder to resist.