Lawsuits may be key to tighter US data privacy rules

Facebook is under pressure to review its data privacy rules following a data harvesting scandal with a UK firm

Updated: Apr 5, 2018

Facebook on March 21 announced further limits on apps that gain access to its users' accounts. The move comes after Facebook suspended a UK political consulting firm, Cambridge Analytica, following allegations on March 18 that it improperly obtained personal data on 50 million Facebook users that was subsequently used in political campaigns. The incident has reignited the debates in the United States and elsewhere on online privacy, targeted messaging and whether tech firms are now too powerful to be left to regulate themselves.

What next

Facebook will need to rebuild trust with its users after its latest but largest data privacy scandal and tardy public response. Increasing calls for regulating the social media platforms will fall foul of political partisanship in the United States. User abandonment of Facebook is also unlikely to get sufficient traction to force the company to change its business model. However, lawsuits against Facebook by investors and users will be more likely to lead the company to tighten up lax monitoring and enforcement of terms of service concerning use of users' data by third parties.

Subsidiary Impacts

- First Amendment considerations will limit any efforts to control online political advertising in the United States.

- Accusations that Facebook facilitated foreign meddling in elections will dog it more than allegations of improper acquisitions of user data.

- Internal criticism of Facebook's practices by employees, former employees and investors may be greater agents for change than lawmakers.

Analysis

Facebook's Cambridge Analytica scandal does not concern a data breach, such as occurred with Yahoo in 2013, 2014 and 2016 or Equifax in 2017, but what Facebook founder and chief executive Mark Zuckerberg calls a "breach of trust".

There are three immediate concerns:

- whether Cambridge Analytica improperly acquired data in 2014-15 on 50 million Facebook users, which was subsequently used in Donald Trump's 2016 presidential election bid;

- whether or not Cambridge Analytica deleted the data as requested by Facebook in 2015; and

- whether Facebook has been sufficiently diligent in enforcing its terms of service.

Cambridge Analytica at the time had contracted a third company to undertake research on its behalf in the United States. When Cambridge Analytica understood that the data violated Facebook's conditions, it certified that it had deleted it. However, Zuckerberg now says that he doubts that it did. Cambridge Analytica denies any wrongdoing.

Legislators in the United States and Europe have called for the company to explain itself before them. The US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is investigating whether the incident means Facebook violated a 2011 consent agreement over past privacy failures.

The scandal raises several broad issues concerning social media platforms.

Consumer privacy rights

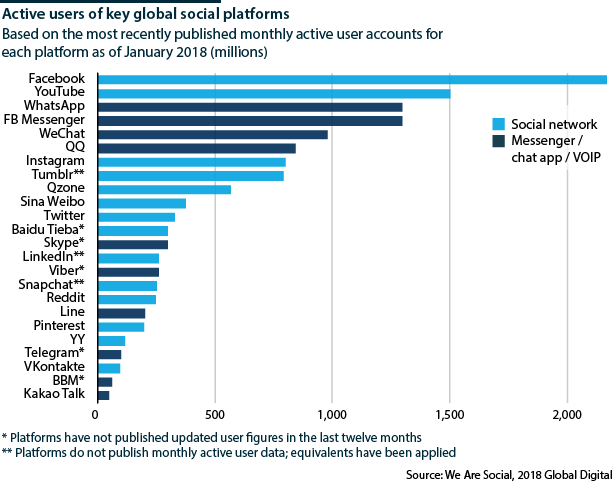

Facebook's business model is a traditional media one: assembling an audience, then segmenting and selling it to advertisers. Facebook has assembled an audience of unprecedented size, 2 billion users, making it the largest social network and allowing it to target messaging with unprecedented specificity.

2 billion

Number of Facebook users

At the heart of this is its Social Graph, based on the application of graph theory to social interactions, allowing a mapping of the network of connections, relationships and online activity between all Facebook users and beyond. Without this ever-expanding personal data trove, to which users agree to contribute when signing up for a Facebook account, Facebook would not be able to let advertisers optimise their messaging by targeting it so specifically.

In 2010, Facebook opened its Social Graph to developers and other third parties (such as the researcher who supplied Cambridge Analytica with the controversial data set), so they could build social apps -- and generate even more Facebook activity and data. However, one consequence was that Facebook made it possible for outsiders to collect people's data through their friends, regardless of whether a Facebook user had directly consented to share it with an outside company or not.

Facebook initially did not anonymise the data it allowed third parties to access

Unlike other companies that offer marketers audience segmentation data, Facebook did not aggregate and anonymise its data. In 2014-15, Facebook, concerned that some developers were misusing personally identifiable information, constrained access to its Social Graph.

Those changes are the basis for Facebook's assertion that there cannot be a repeat of the Cambridge Analytica breach of trust. The newly announced restrictions on access to Facebook users' data -- developers will receive less information from the start, be cut off from access when people stop using their app and need Facebook's approval to access more detailed information -- are largely incremental to the major changes of 2014-15, and to be regarded more as part of Facebook's public relations crisis management than a substantive change.

They will also in part seek to address the legacy data issues from pre-2014-15 apps, whose data is still out there.

Undue election interference?

Facebook's ability to optimise messages works as well for political campaigns as it does for commercial advertisers. Because Cambridge Analytica worked for Trump's 2016 presidential election campaign (among many others around the world) and is financially backed by leading Trump donors such as the Mercer family, the scandal has fast fallen foul of the febrile nature of domestic US politics, which may prove a partisan hindrance to efforts to regulate tech companies (see US/UK: Data privacy may fail to gain US traction - March 21, 2018).

Political advertising, by definition, aims to influence voter behaviour. However, much more research will be required to evaluate how much influence highly targeted political messaging has had on the outcome of particular elections, although the work of political consultancies in Africa provides evidence that it is not particularly effective (see AFRICA: Political consultants will have limited impact - July 31, 2017).

Political advertising by definition aims to sway voter intentions

Social media platforms have made campaign messaging easy and cheap to mass-customise, but many of the characteristics derided by its critics have existed for generations. Lyndon Johnson is credited with running the first highly emotional TV 'attack' ad with 'The Daisy Girl' nuclear armageddon spot in his 1964 presidential campaign against Barry Goldwater. Fake news, vitriolic personal attacks and scaremongering in presidential campaigns date back to the first contested US presidential election in 1800.

Light regulation

Political advertising rules in the United States are light and less onerous than in many other developed nations, reflecting First Amendment provisions on free speech. In 2002, the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act set limits to TV campaign ad spending, but the rise of political action committees (PACs) -- which raise and spend money to elect and defeat candidates -- reduce the effectiveness of those limits. Nor did the Act mandate any truth in political advertising.

Social media firms are not responsible for content posted on their platforms

Social media platforms are exempt from even that light regulation. They have broad legal immunity from responsibility for the content posted on their services, which derives from Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. This statutorily confirms that with some exceptions, online platforms cannot be sued for something posted by a user regardless of whether or not the platform moderates posts or sets specific standards.

Reigniting the debate

The Cambridge Analytica case and the earlier data breaches have reignited the debate about whether federal and state governments should exert more oversight over the technology giants. The companies have successfully been blocking any such moves at the federal level, although Zuckerberg and his chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg have both said in the past two days that they would be open to regulation. They gave no indication of what would be acceptable to them.

In February, California Assemblyman Marc Levine introduced state legislation loosely modelled on the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (see EU/UK: Brexit will not defy data protection standard - August 16, 2017).

Levine's bill would establish a data protection authority to regulate how tech companies request and use Californians' personal data and set data-privacy standards for the tech companies, such as standardised online user agreements, rules for removing data from a company's database when users cancel accounts, and prohibitions on 'tests' of new services unless users have given informed consent for their data to be used. Facebook has controversially engaged in such tests on at least two occasions.

California leads efforts to regulate data privacy in the United States

Were Levine's bill to make it into law (which is far from certain), it could create a federal policy template on the basis that in order to comply with California law, tech companies would likely have to adopt nationwide standards based on California's.

The law may get some backing from non-social media tech companies that are concerned that all technology companies risk being tarred by the seemingly lax data privacy enforcement of the social media platforms. This would be the first break in the unified stance of 'Big Tech' against regulation.

US versus European privacy norms

The United States and Europe have different attitudes towards privacy protection. In the former it is mainly seen as a question of keeping government intrusion at bay, whereas in the latter data privacy is viewed more as a basic civil right (see EU: US tech firms will face more privacy challenges - April 24, 2015).

This will make it more difficult to achieve the necessary international coordination of privacy rules that can encompass global corporations such as the US social media companies.

In the United States, the scandal has raised awareness of the stricter privacy protections of Europe, but this will not necessarily translate into greater demands for matching legislation, although pressure for regulation of ad targeting may increase (see EU: US tech firms will face more privacy challenges - April 24, 2015).

Reputation self-management

Hitherto, tech companies have argued that in the name of not stifling innovation they should not be regulated, because the risk of reputational damage and lawsuits provide an incentive for the companies and their executive to act responsibly and ethically.

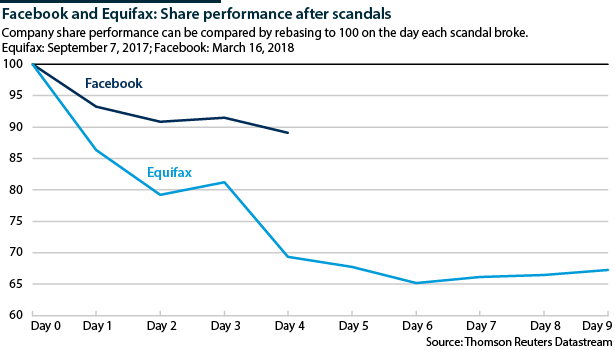

After the scandal broke, Facebook's share price fell only 10% despite the company's slow public response and what has been widely noted as a lack of contrition on Zuckerberg's part. This implies that reputation risk alone is not sufficient incentive.

The company is likely to face a long line of lawsuits seeking damages from users and investors looking for a faster and more direct remedy. On March 20, Lauren Price, a Maryland resident, filed the first class-action complaint against Facebook and Cambridge Analytica (Price v Facebook Inc et al, U.S. District Court, Northern District of California, No. 18-01732). Several hours earlier, Facebook was sued in a shareholder lawsuit (Yuan v Facebook Inc et al, U.S. District Court, Northern District of California, No. 18-01725) for the drop in its stock price after the data harvesting was revealed. More suits are likely.

Business outlook

A consumer and advertiser backlash against digital advertising was underway before the scandal broke.

The number of devices using ad-blocking technology rose to 615 million in 2016, up by 30% year-on-year, according to a report in June 2017 by PageFair, a company that helps publishers regain revenue lost to ad blocking. Google and Apple have both introduced ad-filtering versions of their browsers. Consumer products multinationals such as Procter & Gamble and Unilever have scaled back their online ad spending, questioning its efficacy.

Consumers are already wary of targeted advertising

Whether the data harvesting scandal turns into the existential crisis for Facebook that some have suggested may depend on the extent to which its users consider it to be a 'must-have' compared with the indispensable utility of, say, Google and Amazon. If they do, then privacy concerns and the 'social-media-is-bad-for-society-and-democracy conversation' will be moot. There is no evidence so far that calls for a boycott of Facebook are leading to any significant user abandonment of the service.

Note: Oxford Analytica and Cambridge Analytica have not and have never had any relationship or affiliation. In 2017, Oxford Analytica entered into a trademark dispute with Cambridge Analytica over the term Analytica, for which Oxford Analytica has held a trademark since 1994. The dispute has not yet been resolved as of the date of writing.

_350.jpg)