Militias could push the Syrian president towards Iran

The disputed role of militias creates divisions within the Damascus government and among its allies

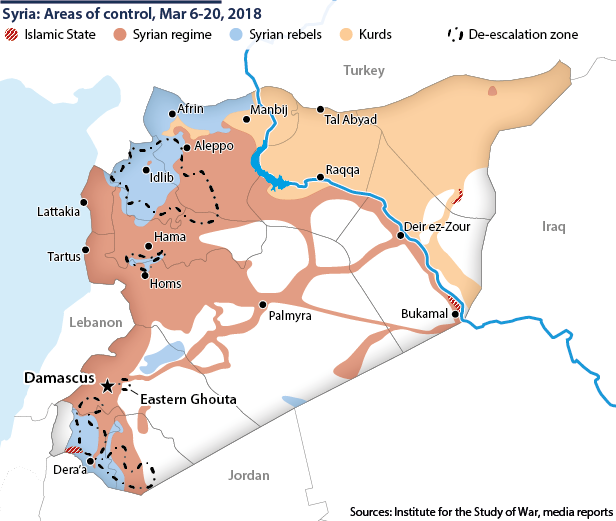

The evacuation of holdout rebel forces from Eastern Ghouta continued today, after a military campaign spearheaded by the notorious Russian-backed, pro-government ‘Tiger Forces’. President Bashar al-Assad does not control most of the local and foreign militias that operate in his name in Syria. Some of those follow the policies of Iran’s Islamic Revolution Guard Corps (IRGC), which face opposition from multiple quarters, including the Ministry of Defence. Neither Lebanese Hezbollah nor all the Iraqi militias deployed to Syria are completely aligned with the IRGC, while Russia often takes an independent stance.

What next

Assad increasingly resents growing IRGC power and influence in Syria, but he also fears that Russian peace plans could push for him to retire. He will therefore align more closely with Tehran, possibly striking a deal to assure his long-term incumbency in return for deputising more power to the IRGC’s proteges.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Damascus may fail fully to exploit its military advantages owing to its inability to control pro-IRGC militias.

- Business interests could push the president to draw closer to the IRGC, in opposition to the Ministry of Defence.

- Assad might lose support within the Syrian military establishment if he is seen as too closely aligned with the IRGC.

Analysis

During the civil war, Damascus has been increasingly reliant on a variety of militias to supplement its ineffective and poorly motivated army (see PROSPECTS 2018: Syria - November 15, 2017).

Foreign influence

From the beginning it depended on funding, trainers and advisers from the IRGC, Hezbollah and several Iraqi groups linked either to the IRGC or to leading Iraqi cleric Ali al-Sistani. This has long created internal disquiet about the extent to which the IRGC in particular might gain influence and power within the Syrian security apparatus.

The IRGC not only brought several foreign volunteer-based militias to Syria (the best-known being the Afghan Fatimiyun and Iraqi Fadl al-Abbas); it also sponsored and managed the establishment of the National Defence Force (NDF), an umbrella structure meant to bring together the many local pro-government militias that sprang up in 2011-12.

The much-feared Tiger Forces have spearheaded recent advances

The IRGC provided training and advice to several other mobile militias controlled by the Syrian intelligence services, such as the Tiger Forces. Sometimes credited with being Damascus's most effective fighting force, under Brigadier-General Suheil al-Hassan, this has now received Russian sponsorship and led recent successful offensives in Deir ez-Zour, Idlib and Eastern Ghouta.

Structural machinations

The militias helped the Assad government regain ground from the armed opposition in 2013-14. By 2015, however, Damascus was concerned that the IRGC had excessive control of local armed groups, as well as foreign volunteers. The government sought to mitigate this by splitting the NDF and creating a new Local Defence Force (LDF) out of those commanders considered to be more loyal.

Even so, by 2017 it was clear that the LDF had failed to break away from IRGC influence. Damascus pulled out those sections it thought it could salvage, such as Liwa Imam al-Baqr and Liwa al-Imam Zain al-Abidain, placing them under the direct control of military intelligence.

Various sources in the militias, the IRGC and Hezbollah estimated in early 2018 that two-thirds of pro-Damascus local militias were more loyal to the IRGC than to Assad. The IRGC staffed the NDF and LDF primarily with members of the Shia community.

In addition, the IRGC still controlled the vast majority of foreign Shia militias in Syria, numbering about 30,000. The government scored one major success when it managed to bring Fadl al-Abbas under its own influence, after many Iraqi volunteers returned home by 2017 and were replaced by Syrians -- but this was very much the exception.

Foreign differences

The only 'competition' faced by the IRGC over the control of the foreign volunteers came from Hassan Nasrallah, head of Lebanese Hezbollah, and to a lesser extent from Iraq's Sistani:

- Hezbollah controlled Liwa Subhi al-Tufayli, a 3,000-strong Lebanese volunteer militia and sponsored (or co-sponsored alongside IRGC) various Syrian Shia militias, including the NDF (about 60,000 men) and LDF (30,000).

- Sistani influences a couple of Syrian Shia militias and three foreign ones: Kataib Imam Ali (over 3,000 men), Kataib Sayed al-Shuhada (several hundred) and Liwa Abu al-Mahdi Mahendis (about 500).

Although Nasrallah and Sistani's supporters are always keen to stress their close cooperation with the IRGC, they also highlight differences. For example, both agree with Assad in rejecting IRGC plans to keep the foreign Shia militias in Syria after the war. More importantly in the short term, both accept Damascus's request that Syrian militias should be multi-sectarian and incorporate as many Sunnis as possible.

2%

Shias as a proportion of the Syrian population/LDF

The IRGC, by contrast, deliberately favours recruitment of Shias, who are overwhelmingly over-represented in the NDF and in the LDF. Whereas Shias (excluding Alawites) are about 2% of the Syrian population, they make up 83% of LDF members and even more of the NDF.

83%

Shias as a proportion of the LDF

In general, Hezbollah and Sistani advocate close cooperation with the Assad government, acknowledging its formal military chain of command. However, the IRGC took the Shia militias it controls, including many Syrian ones, out of Damascus's chain of command, dispatching them on independent, unauthorised operations. In last year's battle for the Deir ez-Zour, for example, Syrian army and pro-IRGC militias were separate and uncoordinated, in effect racing to reach the town first.

In part this is an Iranian retaliation against Assad's objections to IRGC demands for a post-war role for foreign militias in Syria. It also, however, reflects IRGC frustration about the unwieldy modus operandi of the Syrian Ministry of Defence, which has proved unable to deal quickly and effectively with insurgent attacks.

Iranian dependence

Until 2016, Assad was widely viewed within the wider government as aligned with the IRGC and trusting the Iranians more than the Russians -- in contrast to the preferences of the Ministry of Defence. The president and many of his officials believed that Tehran had a longer-term commitment to Damascus than Moscow.

This changed temporarily in 2017, when Assad too became concerned about the ever-expanding influence of the IRGC, fearing that he could become a figurehead in an Iranian-controlled puppet government. In countering Tehran's influence Assad received keen support from Russian advisers in the country (see SYRIA: Damascus will balance Moscow and Tehran - February 9, 2017) and (see RUSSIA/IRAN: Visions differ on Syria's future - March 6, 2017).

By the end of the year, however, Assad began to see Moscow's plan for a transitional government as the greatest threat, fearing it might seek to placate his enemies by replacing him at the top of the government structure. Other controversial issues were Russian efforts to forge better ties with Turkey and incorporate some rebel clients of Ankara into a future coalition government.

At this juncture, Assad therefore has little option but to turn to back to Iran for support. Indeed, in early 2018 he reportedly gave in to some key IRGC demands: for example, appointing pro-Iranian militia commanders to senior positions in the Syrian security apparatus.

_350.jpg)