Lebanon will struggle to turn loans into prosperity

International allies have promised financial support ahead of pivotal elections

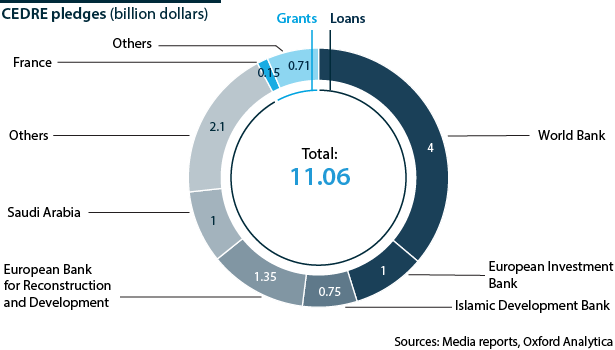

President Michel Aoun yesterday signed the 2018 budget, which meets many donor demands for fiscal reform. Lebanon won aid pledges exceeding eleven billion dollars on April 6 during a conference in Paris, named CEDRE, that aimed to rally international support for a massive investment programme. The funds will be used to overhaul infrastructure and lift dwindling economic growth.

What next

In the short term, Prime Minister Saad al-Hariri will seek to translate the Paris deal into political backing ahead of the May 6 parliamentary polls. In the longer term, the government faces a hard task to implement reforms and balance the budget, given rampant high-level corruption. Internationally, the pledges signal continuing strategic interest from Europe and the United States in protecting Lebanon from bankruptcy -- highlighted in a recent IMF report as a real possibility.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Popular hopes for an economic upswing may help Hariri retain his premiership after the May 6 elections.

- Direct involvement of the Saudi private and public sector in infrastructure development could seal the Beirut-Riyadh rapprochement.

- Conflict between Israel and Lebanese Shia political-military movement Hezbollah would upend all reform plans and destroy the economy.

Analysis

After the CEDRE meeting, Hariri emphasised that the deal could lift Lebanon from looming economic collapse to renewed growth. He also used the meeting to promote political ties, posting a 'selfie' with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman that suggested an improvement in their relations following last year's alleged kidnap (see LEBANON: Deeper Iran-Saudi conflict will hurt Beirut - November 8, 2017).

While Paris provided Hariri with a chance to demonstrate statesmanship, the loans have received a mixed reaction from the public, with many sceptical editorials and social media commentary. (Hezbollah was especially critical, as the party was excluded from CEDRE.) It is therefore far from certain that these promises will translate easily into electoral success for Hariri and his Sunni Future Movement.

Cash injection

CEDRE pledges consist of 10.2 billion dollars in loans and 860 million dollars in grants. These, together with other recent promised funds, represent a critical injection of cash but also add to the country's mounting debt (see LEBANON: Government may miss economic opportunities - September 27, 2017).

Lebanon already received 500 million dollars in pledged loans from France and other countries to boost its army and security sector at the Rome II conference on March 15. A third meeting, scheduled soon in Brussels, will centre on Lebanon's approximately one million Syrian refugees and could add funding to state institutions (see MIDDLE EAST: Refugees could face forced repatriation - May 31, 2017).

Capital investment

The CEDRE money will be used to implement the first of three four-year phases of an ambitious 16-billion-dollar capital investment programme. This includes around 250 projects in the electricity, water, and waste management sectors and other areas of Lebanon's failing infrastructure.

60/40

Public/private split for the planned investment programme

In stark difference to the past three Paris conferences, the private sector is expected to play a significant role. It will finance around 40% of the programme, with grants and loans used for the remaining 60%. Local contractors are enthusiastic about the prospect of buying into potentially lucrative projects co-funded by government or donors, which could therefore stimulate some private-sector-driven growth.

Economic imbalances

The plan to take much more credit than grants has drawn criticism from Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, as well as Lebanese economists who fear that further loans will push the country over the edge. They argue that, with an interest rate of around 1.5% over a period of 20-30 years, payments will likely exceed growth even if economic reforms succeed.

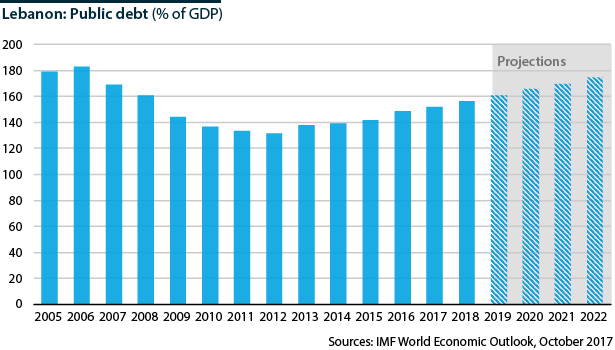

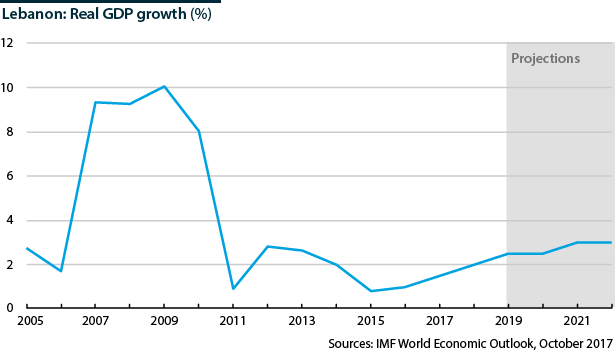

With a public debt estimated at 150% of GDP (or 79 billion dollars) and rising, Lebanon is the third most indebted country in the world, after Japan and Greece. Even on the back of high growth rates between 2007 and 2013, Beirut has not been able to reduce debt or restructure its economy towards fiscal balance.

IMF alarm

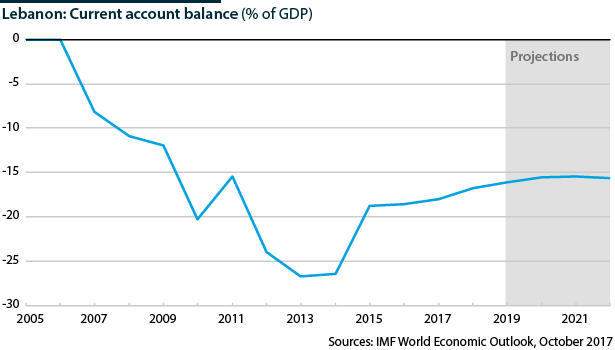

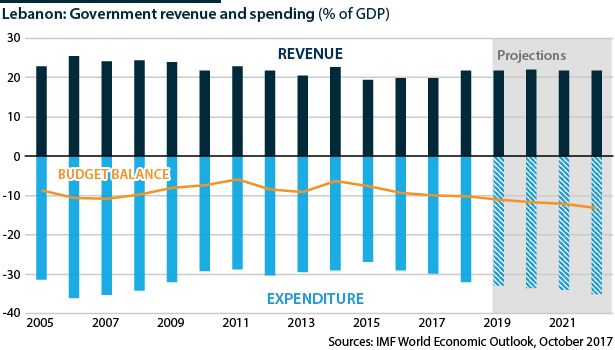

A recent IMF statement, which went uncontested by the government, painted a bleak picture. Real GDP growth has subsided to anaemic levels, currently around 1%. The current-account deficit tops 20%.

Meanwhile, the fiscal deficit stands at 10% of GDP. The IMF emphasised that Lebanon's fiscal policy needs a consolidation plan that stabilises debt and begins to reduce it.

Reform plans

The promised reforms should improve transparency in public finances, mainly by involving the private sector more in state-driven projects. Loans will be geared towards finding lasting solutions for failing infrastructure. In particular, the electricity sector, which costs Lebanon 2 billion dollars yearly and 33 billion since 1993, needs urgent reorganisation.

However, there are several deterrent factors. Large-scale engineering solutions will take time to plan and implement, but the waste, water and electricity problems are urgent, inviting inefficient stop-gap measures such as off-shore ships providing electricity.

To date, political disagreements based on individual (and often corrupt) economic interests have stymied decisions, with particular criticism often directed at Amal and Hariri's Future Movement. Large-scale reforms would require greater political unity and focus on national interest.

An election upset in May could overturn economic planning

The success of reforms hinges in part on the May 6 election (see LEBANON: New electoral law favours sectarian parties - June 22, 2017). If the results are inconclusive and lead to a drawn-out or controversial government formation process, it will make reforms difficult and halt external funding. Notably, if Hariri -- a key figure at the CEDRE conference, gathering international trust and support -- loses to Sunni rivals from Tripoli, donors may lose confidence in the reform programme.

Old legacies

Critics also point to the limited impact of previous packages. The CEDRE conference is the fourth in a series of French-led meetings to stimulate Lebanon's economy:

- At Paris I in 2001, France provided more than 500 million euros in exchange for Lebanon modernising its tax system.

- At Paris II in 2002, the international community pledged around 4.4 billion dollars, of which Lebanon has received roughly half, as the country failed to implement public-sector reforms promised at the meeting.

- Paris III in 2007 saw further pledges of 7.6 billion dollars, intended to break a political crisis that paralysed the country until 2008.

Most of the loans from Paris I-III remain frozen, as the government has failed deliver anti-corruption reforms. However, with the Syrian refugee crisis, depressed growth and the recent IMF report pointing out the dire fiscal situation, a consensus could emerge among Lebanon's ruling parties that the economy is in real danger of collapsing and the state could go bankrupt.

Wary donors and investors

The parliament recently passed a contentious budget for 2018 -- only the second in twelve years -- to show potential foreign investors and donors that Beirut is taking economic reforms seriously. It promises to decrease the fiscal deficit, now at a peak of 4.8 billion dollars -- double the level in 2011 when the war in Syria started.

Donors will be watching to see if a new government lives up to this commitment. To convince them, it must also produce fast and ambitious plans to reform waste management, energy and water.

If not, the CEDRE plan is likely to produce mostly frozen loans and temporary measures that will neither restore investor confidence nor produce an economic upturn.

_350.jpg)