Field remains open as Brazil election campaign begins

The election outcome remains wide open as Brazil gears up for the campaign

On July 26, a coalition of five smaller centre-right parties endorsed the presidential candidacy of Social Democrat Geraldo Alckmin. The coming weeks will see the definition of vice-presidential candidates and the coalitions behind the leading contenders, ending some of the uncertainty surrounding the Brazilian elections. However, the outcome is unlikely to become any less hazy before the October vote.

What next

Parallel disputes will increasingly crystallise within both the left and right camps as contenders seek a path that leads them to the run-off. There is a risk that open and intense horse-trading, especially involving negotiations over future positions among parties theoretically of very different ideological persuasions, will further fuel voters’ rejection of the entire political system. This could lead to a historically high level of blank and spoiled votes, which could ultimately impinge on the result of the presidential contest.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The campaign will likely touch only superficially on the economic challenges facing Brazil.

- Little attention will be paid to the country’s poor productivity and unpreparedness for the digital economy.

- Candidates will note the fiscal deficit but fail comprehensively to address its complex causes.

Analysis

At this point in the last presidential campaign in 2014, all main candidates had their tickets and alliances defined. This year none of the contenders with real chances of winning has reached that stage.

The electoral timeline requires that parties make these decisions in the coming weeks. Party conventions to define candidates and alliances must be held by August 5. A legal loophole may allow some to postpone these decisions until August 15, when candidates and their coalitions must be registered with the electoral authority.

The campaign officially begins on August 16; from August 31, all radio stations and open-air TV channels will broadcast the candidates' campaign advertising. The first round will take place on October 7 and the run-off three weeks later.

Main contenders

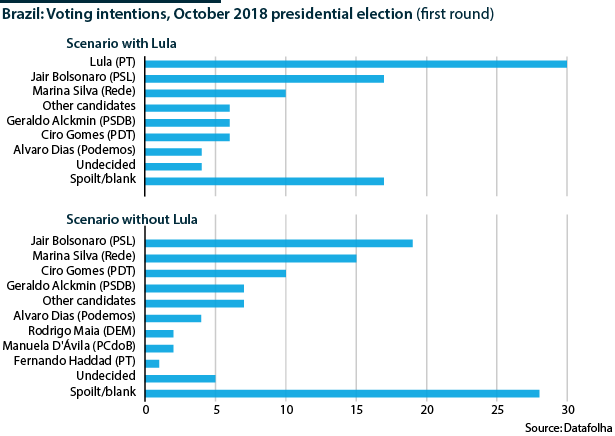

Opinion polls have changed little for several months. They indicate that five candidates have chances of reaching the presidency (see PROSPECTS H2 2018: Brazil - June 19, 2018):

- Jair Bolsonaro, of the Social Liberal Party (PSL) -- a far-right retired military official known for his openly aggressive stance towards minorities;

- Alckmin, of the Social Democrats (PSDB) -- a veteran centre-right politician seen as a competent manager but a poor campaigner;

- Marina Silva, of the Sustainability Network -- a centrist environmentalist also known for her evangelical faith;

- Ciro Gomes, of the Democratic Labour Party (PDT) -- an experienced centre-left politician; and

- former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva or, far more likely, an alternative candidate from his centre-left Workers' Party (PT).

Lula has a comfortable poll lead, but he is currently serving a twelve-year sentence for corruption. The former president, having been considered guilty on appeal, is almost certain to be declared ineligible by the courts (see BRAZIL: Bitter divisions point to uncertain elections - April 9, 2018).

The PT insists it will register Lula as its candidate, which would give the courts until September 17 to bar his candidacy.

Scraping for coalitions

Recent weeks have seen hectic negotiations among parties to muster coalitions -- very often with little regard for ideology. The size of a party's coalition (as measured by its total number of deputies in the Lower House), determines:

- the total free TV and radio time its candidate enjoys, which despite the increasing role of social media in politics remains crucial to communicating with voters, especially those from lower-income backgrounds; and

- the share of public campaign funds it receives, critical in the first presidential elections to be held following the banning of private campaign donations.

Large coalitions also boost presidential hopefuls' chances by granting them the support of candidates to state governorships, as well as of many of those running for state and federal deputies, all of which will be on the ballot in October.

Coalition-building is proving challenging for parties this year

In a country with 35 officially registered political parties, this makes building a coalition -- and, with it, choosing a vice-presidential candidate -- a difficult task. This is especially the case in an open election in which additional daily seconds of TV time throughout the country could make a difference, a situation that strengthens the hand of otherwise insignificant small parties.

Left and right disputes

Despite the usual appeals for unity, the left remains divided.

Gomes's chances will improve if he manages to attract the support of the Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB), a possibility the PT is working to prevent as it could endanger its lingering position as the hegemonic force on the left.

The prospects for the PDT candidate will also improve if Lula fails to 'transfer' a significant share of his votes to the PT's final candidate, placing Gomes firmly as the centre-left's leading contender.

The coming months will also likely see a fierce fight to be the right's candidate in the run-off. So far, the extreme-right Bolsonaro has maintained a margin of around 10 percentage points over Alckmin, who is yet to reach double digits.

Nonetheless, the more moderate candidate seems to be building some momentum. He has won the endorsement of a bloc of five medium and small centre-right parties -- the Progressive Party, Democrats, Solidarity, Brazilian Republican Party and the Party of the Republic -- which until recently were also in talks with Gomes. However, Alckmin's mooted running mate, businessman Josue Gomes, has declined to stand.

This endorsement may boost Alckmin's chances of recovering at least part of the conservative vote that has traditionally gone to the PSDB but has recently been tempted by Bolsonaro's nationalistic rhetoric (see BRAZIL: Military profile rises but coup is unlikely - July 2, 2018).

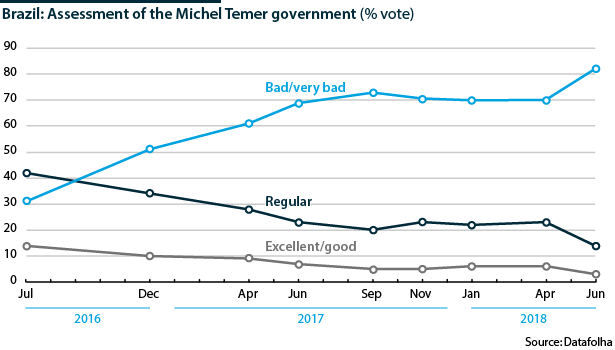

The PSDB candidate still faces an uphill battle to avoid being tarnished by the association between his party and the 'toxic' government of President Michael Temer, which it has supported (see BRAZIL: Centre struggles to promote credible candidacy - March 1, 2018).

Leaders without allies

Bolsonaro and Silva have struggled to build significant coalitions, although they currently lead opinion polls in scenarios without Lula. Recently, the environmentalist leader has admitted that her Sustainability Network might join alliances in state gubernatorial races with parties that do not support her candidacy at the national level. This would increase its chances of expanding its slim caucus in Congress.

Small alliances could weaken current poll leaders

While Bolsonaro and Silva have very different programmes and even personal styles, they encounter a common difficulty. Running from small parties, their inability to attract allies (or unwillingness to make concessions to them) will leave them with exceptionally little free TV and radio time and will therefore reduce their exposure vis-a-vis other contenders.

They will hope this weakness can be offset by the fact that they have not been affected by Brazil's sprawling recent corruption scandals and that they can attract voters who identify with their defining positions -- Bolsonaro's populist nationalism and Silva's environmentalism and, to an extent, evangelical faith.

With an extremely fragmented vote and high levels of spoiled ballots possibly weakening candidates more commonly identified as 'traditional' or mainstream politicians, this could be enough to take one (or even both) of them to the run-off.