'Made in China 2025' will evolve under US pressure

China's 'Made in China 2025' plan has become a byword for practices that US firms and policymakers consider unfair

At the heart of the current US-China confrontation over trade and investment is China's ambition to challenge US technological and industrial superiority. This ambition is now often treated as synonymous with its best-known element, the 'Made in China 2025' initiative (MIC 2025) -- a grand plan that sets ambitious targets for expanding high-end manufacturing.

What next

To maintain its technological advantage, the United States might target MIC 2025 in ways that go beyond the WTO’s framework, which treats non-tariff barriers and countervailing measures as short-term approaches with a fixed time span. Beijing might respond by lowering the profile of its industrial policies and reducing the amount of information it discloses, especially with respect to critical projects in priority industries.

Subsidiary Impacts

- An uneasy relationship between China and the West regarding technology might delay release of technical standards for emerging technologies.

- China will invest heavily in its basic scientific research capabilities, but will not match the United States any time soon.

- It may become more difficult to obtain critical information on high-tech sectors and policies if government decides to downplay them.

Analysis

Google web searches for 'Made in China 2025' almost doubled this July in the United States, according to Google Trends. Most searches came from the District of Columbia.

The MIC 2025 plan was released in May 2015 and a month later a leading group headed by Politburo member and Vice-Premier Ma Kai was set up to oversee its implementation. The plan was updated in January this year.

However, officials at the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) have repeatedly insisted that the ambitious targets set under MIC 2025, unlike China's regular Five-Year Plans, are not an official policy.

One reason why Chinese officials refuse to recognise MIC 2025 as an official policy is because it sets quotas for self-sufficiency in high-end technology that could violate WTO rules against technology substitution.

So MIC 2025 is called a 'guiding framework' and official policies have been released for each specific industry (for example, the Next-Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan) (see CHINA: AI plan lays foundation for long-term strength - July 9, 2018).

In 2017, China released eleven supporting implementation and action plans for specific industries and the High-end Smart Remanufacturing Plan (2018-20) for implementing MIC 2025.

So China's industrial policy since 2015 can be best understood as operating under the framework of MIC 2025 through other official policies that operate in a top-down, coordinated and state-directed fashion that is implemented with the combined support of provincial governments, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private enterprises through institutional backing, often set up in the form of industry financing vehicles.

A US Chamber of Commerce report on MIC 2025 noted the announcement in Chinese media of roughly 800 state-guided funds with a combined value of 2.2 trillion renminbi (320 billion dollars) across a range of industries to support MIC 2025. Much of this funding is granted to SOEs and in accordance with provincial government plans.

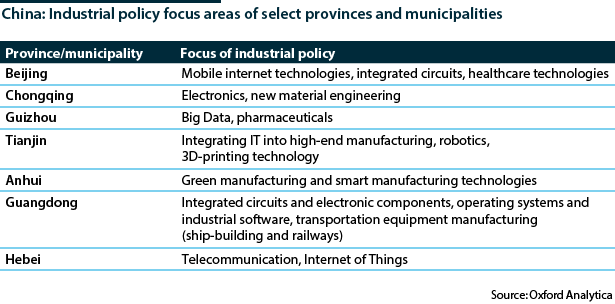

Provincial governments often have a strong role to play in industrial policy. Local governments release their own five-year plans alongside the central government's and are responsible for financing and implementation of those plans, under direction from Beijing. SOEs based locally also have a role.

A top-down framework implies coordinated actions by stakeholders and institutions

Top-down policymaking

Top-down policymaking means that stakeholders are often connected across institutions and operate in a coordinated fashion, especially for the critical technologies labelled 'priority industries' under MIC 2025.

Tsinghua Unigroup -- the wireless systems chip designer whose 23-billion-dollar bid for Micron Technologies in 2015 was blocked by the US government -- is an example of how SOEs, public institutions, private investors and industry alliances are interconnected.

Tsinghua Unigroup is 51% owned by Tsinghua Holdings, a wholly owned subsidiary of Tsinghua University (and hence an SOE). The remaining 49% stake is owned by Beijing Jiankun Investment Group, an asset management firm led by Zhao Weiguo, the deputy director-general of the China High-End Chip Alliance.

A top-down directive pushes all such stakeholders in a single direction, for example, to improve China's semiconductor design and manufacturing capabilities.

The interlinkages within China's industries allow innovative strategies in response to technological restrictions imposed by the United States (such as the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States blocking Chinese technology sector investments) (see CHINA/US: Neither side will budge on tariffs - July 11, 2018).

R&D in China focuses on quantity rather than quality, and experimental development rather than basic science

R&D focus

China invested roughly 291 billion renminbi in high-technology industries in 2016, National Bureau of Statistics data show.

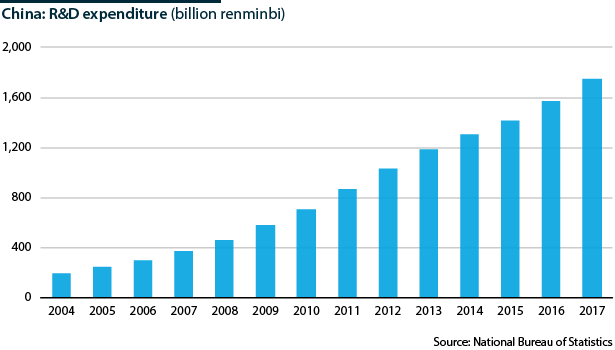

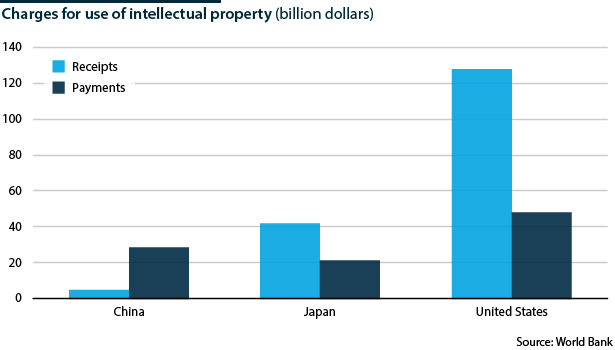

It is catching up with United States in R&D spending, but quality-adjusted measures of scientific production (publications among the top 10% most-cited) show China lagging far behind. This is reflected in its balance of payments for charges on use of intellectual property rights (patents, trademarks, copyrights, industrial designs and trade secrets).

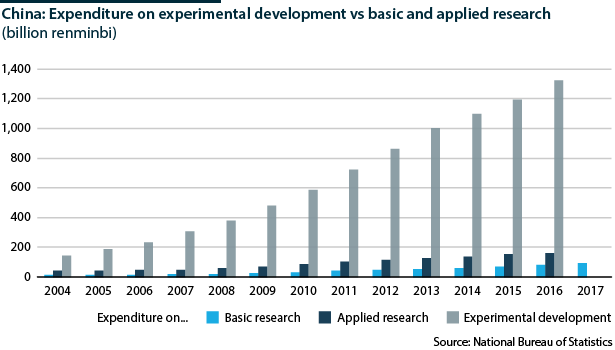

One of the reasons is that most of the R&D funding in China is directed towards practical uses for the market and is usually carried out by the private sector, instead of basic and applied research (which focuses on studying scientific phenomena and does not have any short-term marketable returns).

Such focus on experimental development allows China to upgrade its technological capabilities through rapid product and process innovation (the reason China has gone from 'copycat' to an 'innovator'). However, unless it develops a knowledge base relevant to basic research, China cannot rival the technological and scientific pre-eminence of the United States.

Chinese policymakers wish to change that and are spending generously to achieve this goal.