Waste management is key to sustainable global growth

Waste management addresses over half of the 17 high-level goals in the UN's post-2015 sustainable development agenda

The World Bank estimates that by 2025 cities will be creating 2.2 billion tonnes of solid waste annually, nearly double the 1.3 billion tonnes produced in 2012. Systems to manage vast quantities of urban waste already account for more than 20% of many cities' budgets, and this will rise. Yet despite the cost, the profile of waste management lags other utilities, hampering the ability to attract political attention and financing to build, improve and maintain effective systems.

What next

Increasing urban populations could overwhelm waste management systems already reaching breaking point in many countries; the number of people living in urban centres overtook those living in rural areas in 2014 and the UN expects the ratio to rise to two-to-one by 2050. Circular development is critical to sustainable waste management; minimising initial waste production and then treating it as a resource. The multitude of stakeholders and coordination throughout the material transition from product to waste is complex, thus systemic improvements will be slow.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Manufacturers and product designers will increasingly be tasked with preventing the creation of waste, not merely reducing its footprint.

- Integrating waste and resource management into the education curricula will foster generational behaviour change.

- Waste-pickers collect, sort and recycle up to 20% of developing countries waste; policies will increasingly support informal workers.

- Fee structures to manage waste will move to point-of-purchase rather than using municipal taxes to raise fees at the point-of-collection.

Analysis

To reduce or eliminate the need to landfill or burn waste, municipalities are increasingly designing policies and programmes to manage waste at source and at the household level.

The income divide

The challenges associated with waste management differ between high-income countries (HICs), defined by the World Bank as having a per capita income of 12,056 dollars or more in 2017, and low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs), with a per capita income of 1,026-4,035 dollars.

In HICs, the challenge is improving waste management systems and implementing circular development. The immediate LMIC challenge is to minimise uncontrolled disposal and to increase access to waste collection.

Waste reduction and governance of waste management systems will grow in importance as the population of major urban areas in LMICs is expected to double over the next 20 years.

Quick action can bring significant benefits. UN Environmental Programme research suggests that the cost of LMIC cities taking no action could be five to ten times higher per capita than the cost of a properly functioning waste management system.

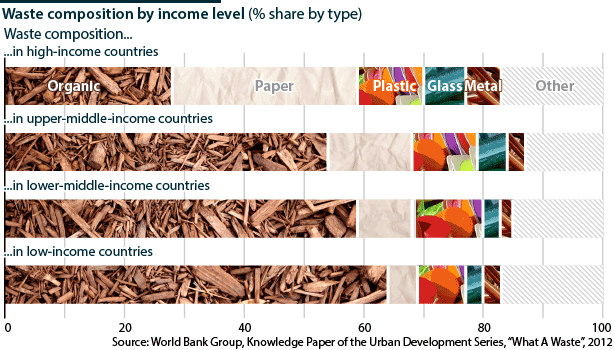

High-income countries produce much more paper and plastic waste than lower-income countries

The term 'waste' includes multiple forms and compositions of waste. The composition of waste determines how management systems operate and what technologies are employed.

World Bank research shows that in LMICs, 59% of waste is biodegradable, materials that break down and decompose as compost, versus 28% in HICs. However, 54% of waste in HICs is recyclable and can be repurposed through chemical change, shredding or remelting. In LIMCs, 19% is recyclable. Inert materials that neither break down and decompose nor are nonrecyclable comprise 18% of waste in HICs and 17% in LMICs.

The share of inert materials is almost identical across country income levels but low-income countries are much less likely to have formal waste management systems. For countries without formal systems, a common method of reducing waste in cities and homes is burning it, uncontrolled or in open fields.

The UN estimates that 41% of global waste is burned openly. The share is higher in LMICs where the practice is often unregulated. In HICs, uncontrolled burning predominately is banned. LMICs are moving toward bans but will struggle to enforce them as much of the waste that is burned never enters a waste management system.

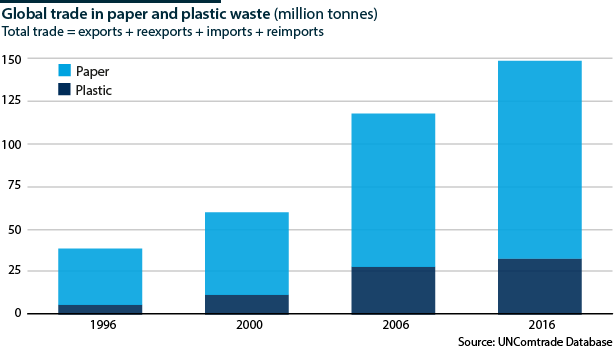

Chinese ban

After 26 years of receiving nearly half of the world's refuse, China stopped accepting plastic waste and low-value paper imports this year (see INT: China's waste ban will encourage innovation - January 9, 2018). In June, scientists at the University of Georgia published a paper, 'The Chinese import ban and its impact on global plastic waste trade', showing that from 1992 to 2016, China accepted 106 million metric tons, or 45% of the world's plastic waste.

70%+

Of waste produced since 1950 is in landfills, recycled produce or the environment

Estimates suggest that 8.3 billion-9.0 billion tonnes of plastic waste has been produced since 1950, and more than 6 billion tonnes of this still sits in landfills or is in oceans and on seabeds causing environmental damage.

Plastic

Plastic collection and recycling is the most recognisable waste management programme, especially in HICs (see INTERNATIONAL: Plastic bans will rise, reuse is hard - August 7, 2018). However, the Chinese ban is exposing a lack of recycling infrastructure across the West. Recycling plastic is tenuous economically. Different types of plastic cannot be recycled together, making it only economic to recycle standard items such as drinks bottles.

United States

US recycling operators are unable to keep up with the additional volumes that they previously would have shipped abroad. In the states of Massachusetts and Oregon, restrictions against pouring recyclable material into landfills have been lifted to give recycling centres some relief. The study calculates that if Europe and the rest of the world experience the same difficulties as the United States, an estimated 111 million metric tons of plastic waste will pile up by 2030.

India

India produces nearly 170,000 tonnes of waste per day, 62 million tonnes of waste per year -- the same amount as Sub-Saharan Africa. Unable to export it, and often unable to collect it, a significant amount of waste is dumped and often burned, reducing air, soil and groundwater quality and potentially acting as a transmission channel for disease.

In 2017, in the village of Koorachundu in Kerala state, more than 55% of the residents contracted fever from mosquitos after waste piled up while insects were breeding ahead of the monsoon season.

India produces more waste per year than the whole of Sub-Saharan Africa

In 2017, the UN Environment Programme listed Alappuzha, a coastal city in Kerala, as among the top five waste management models worldwide. The city began a pilot in twelve wards in 2014. Every family was given aerobic composting bins and biogas plants to segregate and process their garbage in their own composting plants. The composting bins and biogas plants were heavily subsidised.

The source-based waste approach segregates solid waste at the point of disposal. Wet waste is composted in local plants and a significant amount is processed into biogas for cooking. Dry waste is channeled to recyclers.

The programme required reinforcing behavioural changes at a household level to ensure the programme was adopted and correctly implemented.

Alappuzha's approach was original in including changing attitudes to foster collaboration and more appreciation of waste-pickers. Pickers were portrayed as technicians processing waste, not unskilled collectors. Boosting their status noticeably improved waste management.

Waste management in the city has grown to 5,000 kitchen bins, 3,000 biogas plants, 4,000 pipe composting units and 218 aerobic bin units -- managing 80% of the waste produced by the population of 174,000.

The Alappuzha district intends to install aerobic units every 500 metres by 2019 and to provide equipment at a 50% subsidy in the 30% households who have not installed them yet. In May 2017, a delegation from the state of Meghalaya visited to Alappuzha to understand and replicate the system before Shillong, the state capital, hosts the 2022 National Games.