Next year’s elections may reconfigure EU politics

The outcome of the European Parliament poll will influence the overall direction of EU reforms over the next five years

European Parliament (EP) elections will take place in May 2019. The rise of far-right and in some cases far-left populist parties in recent national elections and the departure of 73 UK EP members (MEPs) due to Brexit will likely lead to a shake-up of the pan-European political parties (Europarties) that group together MEPs and organise politics in the EP.

What next

Although centrist Europarties will most likely continue to dominate, their majority will probably shrink, while the influence of populists in the EP will grow. Significant changes in the party system are likely, with some existing Europarties rupturing or collapsing, and new ones emerging. Shifts in the party system may continue after the elections, as individual national parties try to reposition themselves in the most advantageous Europarty.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The most salient axis of competition will not be the traditional left vs right divide, but Eurosceptic populist vs pro-EU centrist.

- If populists make major gains and form effective alliances, this would be seen as a crisis and a threat to the functioning of the Union.

- Shifting alliances in the EP will impact how the EU deals with various national governments.

Analysis

Critics of the EU often wrongly dismiss the relevance of the EP, which has grown into a powerful legislative body, more powerful in many respects than several national parliaments across Europe, which are dominated by their executives.

The EP can amend and vote down EU legislation that affects vast areas of the European economy and it has the power to ratify international agreements entered into by the EU.

Lobbyists know this, which is why thousands of them inundate MEPs trying to influence their lawmaking, but voters still seem to take little interest.

Voter turnout has dropped significantly since direct elections to the EP were introduced in 1979. It fell as low as 42.6% in 2014, and there is little sign there will be an upsurge in participation in 2019.

Party shake-ups

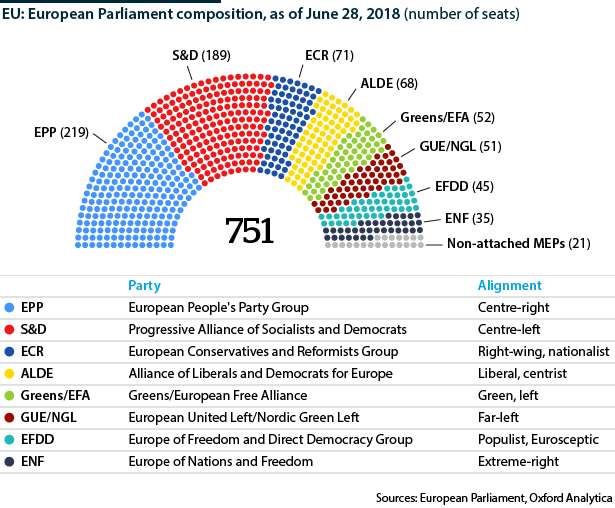

The EP has long been dominated by a kind of grand coalition of the centre-right European People's Party (EPP) and the centre-left Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D).

However, just as has been happening at the national level in many member states, the vote (and seat) share of these centrist parties has dropped as more extremist parties gain support (see EU: Populism will lead to greater fragmentation - March 13, 2018). The EPP and S&D won just fewer than 55% of the seats between them in the 2014 elections.

The current EP party system is made up of eight groups, which each must contain 25 MEPs from at least seven member states.

Not only is the seat share of these groups likely to change significantly after the 2019 elections, some groups may disappear altogether, while new ones may form. There is a considerable chance of the EPP and S&D dropping below 50% of the seats collectively, which might require them to share power with another party.

Reshuffling the deck

The shake-up of the Europarties may continue in the weeks after the elections, as individual national parties shift allegiances between groups.

The EPP is likely to remain the largest group and to continue to dominate EU politics. However, the dominance of the EPP together with the S&D is threatened on many fronts.

Populists rising

Far-right populists who have made major gains in several EU member states including Italy and Germany are hoping to collaborate more effectively at the EU level to disrupt centrists' control of EU politics.

Matteo Salvini, the Italian deputy prime minister and leader of the League party, has called for forming a pan-European anti-immigration alliance -- a 'League of Leagues'.

Marine Le Pen, leader of France's National Rally (formerly National Front), has launched a Union of European Nations alliance to increase the power of like-minded forces at the EU level.

In July, US President Donald Trump's former policy advisor Steve Bannon backed an umbrella group called The Movement, in hopes of uniting Europe's far-right nationalist parties.

It is unlikely that far-right populists will form a single, coherent group

While far-right and assorted populist forces are likely to make gains in the 2019 EP elections, they are unlikely to win more than about 20% of the seats or succeed in forming a single, coherent political group.

These parties have a long track record of discord at the EU level and despite efforts to unite them, they are likely to remain divided among two or more different political groups.

Macron en marche

France's President Emmanuel Macron hopes to remake the landscape of EU-level party politics just as he did in France with his En Marche movement.

Rather than join an established Europarty, Macron has been exploring the possibility of forming a new group with Spain's Citizens and others.

To succeed, Macron would have to peel off several parties from the EPP, S&D and the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE). Though this is possible, it seems more likely he will join the liberal ALDE, perhaps under a new label.

Shrinkage

According to the EU treaties, the number of MEPs cannot exceed 751 (750 plus the president of the EP).

With the departure of the United Kingdom from the EU, the overall number of seats in the EP will be reduced by 46, from 751 to 705 (see EU: Integration will deepen incrementally post-Brexit - April 4, 2018).

The United Kingdom's 73 MEP will leave but instead of simply shrinking the EP by 73 seats, 27 of those seats will be reallocated among 14 member states that were deemed to be underrepresented.

In effect, the remaining 46 seats freed up will be held in reserve to be allocated among new member states that might join the EU in the future.

The United Kingdom's departure will have a major impact on the party system, as the Conservatives and the UK Independence Party were the largest parties in their respective Europarties (the nationalist European Conservatives and Reformists, and the Eurosceptic Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy). These groups may collapse without them.

'Spitzenkandidat' process

The Europarties are likely to rerun the 'spitzenkandidat' (lead candidate) process inaugurated in the 2014 elections, whereby they put forward candidates for the Commission presidency and then demand that member state governments in the European Council select the candidate of the party that won the most votes. In 2014, it resulted in the selection of Jean-Claude Juncker as Commission president (see EU: Commission presidency spat threatens policy agenda - June 4, 2014).

Barnier may be the most likely next Commission president

Most observers see the EU's chief Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier as the most likely spitzenkandidat for the EPP, and hence the most likely to emerge as Commission president.

Though the process was controversial at the time (as it has no firm treaty basis), MEPs insist it is necessary to improve the democratic legitimacy of the Commission and the EU as a whole.

The fact that the outcome of the EP election now determines who becomes Commission president has raised the stakes.

This helps explain why the EPP has been so supportive of such controversial figures as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, whose party is accused of violating some of the EU's fundamental values (see HUNGARY: Fidesz win will bring more conflict with EU - April 10, 2018).

It seems likely that EPP leaders will continue to tolerate illiberal national member parties, provided they help them gain the seats they need to prevail in the EP elections.