Taxes offer an alternative to tariffs

New modelling implies that progressive taxes are a better equaliser for the winners and losers of trade than tariffs

The creation of winners and losers is at the core of the public debate surrounding international trade. Some workers benefit from having a comparative advantage in international competition, but many that do not, lose out from trade. The winners tend to take their good fortune for granted, but the losers feel their pain acutely.

What next

The United States is pursuing policies to protect and assist those disadvantaged by the forces of international trade, but recent research finds that in no cases do tariffs improve welfare. Instead, they risk eroding living standards for a segment of the population for the benefit of a smaller group. The optimal policy mix, ripe for exploration, appears to be zero tariffs and tax systems growing more progressive as exposure to trade grows. However, US policy seems unlikely to change direction in the near term.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Concerns will persist; research shows that Chinese import exposure lowers US labour participation, incomes and social assistance take up.

- Progressive taxation helps workers, but disincentivises moving from low- to high-productivity locations; policy will need to consider this.

- The US tax system has historically become more regressive as the economy has opened to trade; changing direction would reduce inequality.

- Increasing tax policy progressivity as automation accelerates will ease worries about the negative effects of technological progress.

Analysis

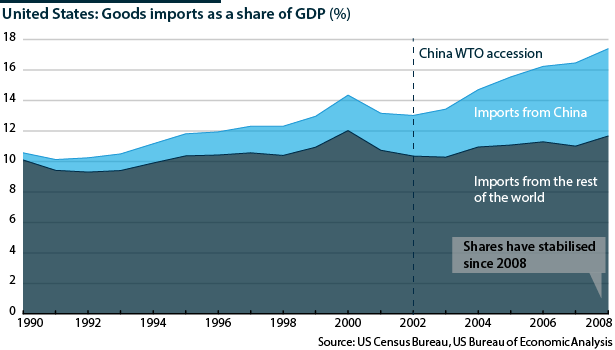

In 1990, imports from China accounted for 1% of US GDP and total imports 10%. By 2007, imports from China accounted 7% of US GDP and all imports for 17%. The segments of the US labour market that were most exposed to increased Chinese import competition suffered.

Research by economists Autor, Dorn and Hanson in 2013 shows that Chinese import competition led to lower labour income (in relative terms), workforce participation and take up of social assistance (see UNITED STATES-CHINA: Tariffs - August 9, 2018). The paper finds that import competition explains 25% of the decline in US manufacturing employment between 1990 and 2007.

Mobility

Traditionally, economists assume that labour can quickly move to the locations, sectors and firms that offer better employment and wage opportunities. However, these adjustments do not occur quickly enough to avoid interim losses. Transfer schemes can compensate the losers from trade while preserving some of the gains for the winners, but policymakers face practical constraints implementing any direct transfer scheme.

Insuring against bad luck

Some economists just accept that the benefits and costs of trade are unequal. However, research by Waugh and Lyon in 2018 suggests that the government does have tools to address these concerns. The authors model international trade making two core assumptions, that there are underlying frictions in the economy and that governments can partially overcome these by providing social insurance.

Some people are lucky -- in the right place at the right time, or they enjoy good health or benefit from technological advances. Others are unlucky, but society can insure against this outcome.

Progressive taxation

One way to insure against potential losses from misfortune is progressive taxation, as Google's chief economist Hal Varian proposed in 2001. Incomes become less different after tax if the lucky face high marginal rates and the unlucky face lower rates.

A dynamic, prosperous economy requires workers to move from low productivity to high productivity locations, sectors and firms. In general, people have incentives to do so. Low productivity places pay low wages, high productivity pays higher wages.

Adam Smith's "invisible hand" shows that the private incentives to move in response to market prices lead to good aggregate outcomes. However, if the government is too generous in its provision of social insurance, people have fewer private incentives to move, and the aggregate productivity gains from reallocation are lost. This is the cost of progressive taxation.

Social insurance costs and benefits

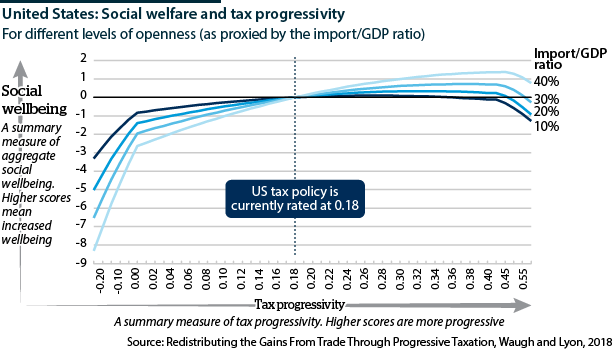

The tension between the advantages of social insurance and disadvantage of taxation create an 'inverted-U' shape. Social welfare (a measure of aggregate wellbeing) relative to current US policy is on the vertical axis and US policy is close to zero on a scale of -7 to +1. The horizontal axis shows the progressivity of tax policy, whereby a larger value is more progressive. On a scale of -0.2 to +0.6, US policy is rated as +0.18.

The peak of the inverted U, which is further to the right than current US policy (i.e. more welfare, more progressive tax policy), represents the policy that optimally balances the benefits and the costs. To the left of the peak, too little social insurance is provided; to the right the tax policy erodes incentives too much, reducing aggregate productivity. The simplest way to move along the curve is to raise the marginal tax rate on top earners and reduce it on lower earners.

Policymakers must balance the benefits of providing social insurance against the costs of making the economy less productive

Openness increasing

The scope for people to be unlucky grows as economies open to trade. The risk of losses in wellbeing increases as job losses and stagnating or falling wages can result not only from domestic effects such as new technologies and tastes but also changes in the international landscape. This implies that demands for social insurance will rise with openness to trade, which suggests that the solution is for tax policy to become more progressive as an economy becomes more open.

Relative to a flat-tax system (top and bottom earners facing the same marginal tax rates), the existing progressivity of the US tax system is already an important tool for enhancing welfare as exposure to trade increases.

For example, the US trade adjustment assistance programme, which is authorised by the Trade Act of 1974 and administered by the Labour Department, provides benefits to workers who can prove they have been displaced due to increased imports or shifts in production to a foreign country. However, research shows that this has been ineffective compared to more traditional and broader schemes including social security and disability insurance.

Historically, the US tax system has become more regressive as the economy has opened to trade (see UNITED STATES: Tax impact depends how savings are used - February 1, 2018). Making the tax system more progressive would redistribute resources from the winners of trade to the losers.

Progressivity over tariffs

Research in the 1970s and 1980s suggested that providing social insurance could be a reason in support of imposing tariffs, but Lyon and Waugh's research models social welfare under various combinations of tax progressivity and tariffs. It finds no situations in which a tariff would improve welfare.

As an economy becomes more exposed to trade, the optimal policy is an increasingly progressive tax system and no tariffs. This suggests that US trade policy is moving in the wrong direction in this regard (trade policy may have competing goals such as to change another country's trade behaviour). Research by economist Dani Rodrik in 1998 established a clear relationship between government size and openness, implying that many countries have used budget spending to provide social insurance to the losers from import competition.

Broader worries about immigration, automation and technological change relate directly to these prescriptions (see INTERNATIONAL: Automation job gains will be uneven - June 26, 2018). Similarly to automation, trade is a labour saving technology, benefiting many, but hurting those that are directly exposed.

As exposure to labour-saving technologies rises (be it automation or trade), increasing progressivity will improve welfare