Polar Silk Road will reshape trade and geopolitics

China and Russia are spearheading a major new shipping route through the Arctic

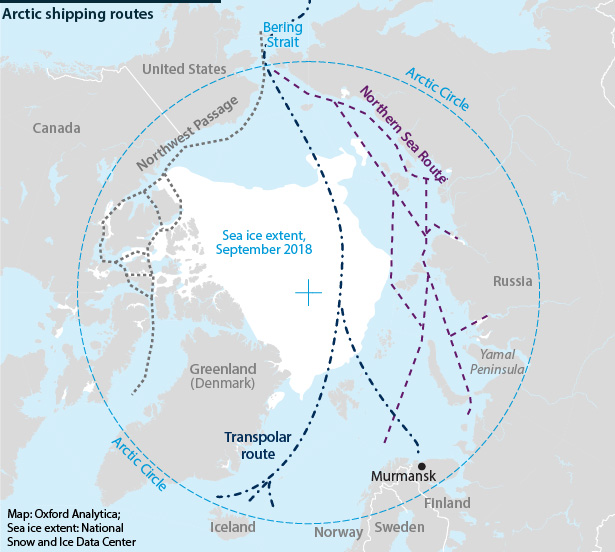

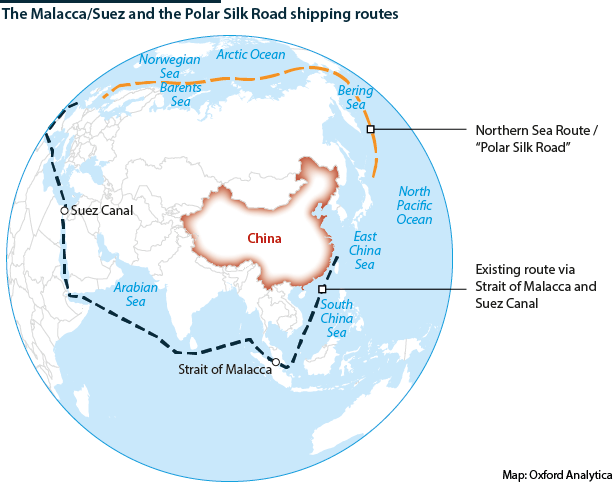

Climate change is leaving Arctic waters navigable for longer periods, opening a new shipping route from East Asia to Europe along Russia's northern coast. Dubbed the ‘Polar Silk Road’ (PSR) in China and 'Northern Sea Route' (NSR) in Russia, it could eventually become an alternative to the main Strait of Malacca and Suez Canal route, altering global supply chains and geopolitics.

What next

Geopolitical competition with Washington will drive Beijing and Moscow to develop the PSR, with Chinese finance and Russian icebreakers and navigational expertise. The cost, danger and difficulty of navigating these waters may prevent the route becoming mainstream in the near future, but it will become increasingly viable over the next decade or two as the climate warms and more 'ice-class' ships and icebreakers are built. Its eventual impact on supply chains and geopolitics will be significant.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The PSR's economic viability is premised on it being a reliable and safe route; that time is still far off.

- Melting ice will unlock new natural resources and commercial opportunities.

- The foremost use of the PSR initially will probably be for shipping resources extracted from the Arctic to markets elsewhere.

Analysis

There is already shipping through the PSR, but not much. Around 1 million tonnes was shipped in total last year -- less than sometimes passes through the Suez Canal in a single day.

However, recent weeks have seen milestones:

- A new icebreaking cargo ship from China's COSCO carried its first shipment from China to Europe.

- The first of what will be regular shipments of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the Yamal peninsula in Russia arrived in China, aboard the first commercial gas tanker to travel the PSR without an icebreaker escort.

- The first container ship to use the PSR is travelling from Vladivostok to St Petersburg -- a trial by the world's largest shipping firm, Maersk.

China's involvement in the Arctic has progressed quietly

China's Arctic aspirations

China included a route to Europe via the Arctic in its 2017 Vision for Maritime Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Including the Arctic as part of the BRI rationalises China's involvement in a distant region in which it has no sovereign claim.

Then, in January this year, the government's public relations department published a 'white paper' on China's Arctic policy. This puts forward the position that China is a 'near-Arctic' state with a legitimate interest in Arctic affairs and expects active involvement in the region.

Geopolitical rationale

Chinese policymakers have long worried about their country's reliance on the Strait of Malacca. The knowledge that the majority of China's trade, including 80% of its imported oil, could be restricted at short notice if the US Navy blockaded the Strait has prompted a search for alternative shipping routes.

Economic rationale

The PSR could reduce the distance to Europe from China by 40% compared to the Malacca/Suez route. The journey from Shanghai to Hamburg, for instance, is 2,700 nautical miles shorter through the Arctic.

Promising partnership

Russia is an attractive partner to China in the Arctic. Beijing does not regard Moscow as a strategic threat. Russia would be unlikely to 'close' the PSR, as the United States might close the Strait of Malacca.

Russia is the country with the most experience in Arctic shipping, and ships of any flag will depend on Russian icebreakers to escort them. Russia has over 40 icebreakers. The United States and China have just two. Building more would be neither quick nor cheap: the US Coast Guard and Navy estimate the average cost of a new icebreaker at 700 million dollars.

Russia is keen to develop the Arctic route in order to collect transit fees and facilitate the extraction and export of hydrocarbon reserves in its far north.

Resource development

The Arctic has deposits of nickel, copper, coal, gold, uranium, tungsten and diamonds, and produces 10% of the world's oil and 25% of its natural gas. The Yamal peninsula contains the world's largest proven gas reserves and until recently was largely untapped.

Chinese financial resources and demand for hydrocarbons complement Russia's need for non-Western export markets and investment in resource extraction.

China was crucial to the Yamal LNG project, the first gas liquefaction plant in the Arctic (see RUSSIA: Successful Arctic gas plant will be repeated - November 9, 2017).

China's Silk Road Fund took a 9.9% stake for 12.1 billion dollars and the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) a 20% stake. Chinese lenders provided further financing at a time when sanctions prevented the Russian company, Novatek, borrowing from Western banks. China supplied the plant's liquefaction equipment.

Planning is now well under way for a second plant on the Gyda peninsula, with agreements signed in November last year between Novatek, CNPC and the China Development Bank.

Arctic resources can be accessed with Chinese investment and transported to China or elsewhere using PSR infrastructure

Other infrastructure

A consortium led by China's Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and China Telecom proposes by 2020 to construct a 10,500-kilometre fibre-optic link connecting China, Japan, Russia, Finland and Norway.

European countries are developing infrastructure at the western end of the PSR. Finland and Norway are discussing a rail link from northern Finland to Norway's deep-water port of Kirkenes. This would be the first rail connection from an EU member state to an Arctic Ocean port.

Barriers to development

The PSR is not a straightforward substitute for other routes, and the shorter distance will not necessarily make it more economical.

Environment

It involves navigating uncharted waters with dangerous icebergs along remote parts of Russia's coastline.

Even with temperatures rising, weather conditions and ice coverage are volatile. Satellite coverage is poor, making navigation more difficult. Progress is slower and less predictable, since ice must be avoided or broken through, making the route unsuitable for shipments with tight schedules. The sea is shallow so shallow-draft ships must be used.

Moreover, for many years to come the route will not be useable all year round. A study last year estimated that even by the end of this century it will only be navigable for several months each year.

Ships

Shipping companies, unaccustomed to navigating icy waters, may deem the route too risky. Insurers will charge high rates, at least initially, and ships will need to be escorted by icebreakers, for which they will have to pay a fee.

For the foreseeable future, 'ice-class' ships must be used, with stronger hulls and more powerful engines. One recent study estimates that ice-class ships are 10-35% more expensive to run.

New icebreaking cargo ships reduce the need for an escort, but are expensive. The LNG carriers travelling from Yamal to China cost 320 million dollars each, some 75% more expensive than an ordinary LNG carrier of similar capacity.

Legal wrangles

Russia claims the right to regulate shipping through the PSR. It charges transit fees and requires shipping firms to use Russian icebreakers.

Beijing explicitly acknowledged this right when Russia agreed to China joining the Arctic Council (the main multilateral forum for Arctic governance) as a permanent observer in 2013.

However, the legal basis of Russia's claim is open to challenge (see RUSSIA: Moscow will press Arctic claims - February 24, 2017).

Lack of intermediate markets

Long-distance shipping usually stops at intermediate ports to load and unload cargo, but the Siberian coastline does not have population centres with their own demand, unlike the South-east Asian and Mediterranean ports along the Malacca/Suez route.

All these factors will slow down the PSR's development.