Prospects for the future of work in 2019-23

Automation and cheaper technology mean that as many as 184 million jobs could be at stake globally in five years

With the declining costs of computing power and advances in a variety of technologies enabling automation of predictable tasks, the employment market is set to witness significant turmoil in the coming five years.

What next

Over the next five years, jobs lost in developing economies will exceed those in developed economies, due to the much larger workforce in the former. The overall technological disruption could result in a net gain for workers in terms of skills and wages, but governments would need to improve educational and social provision to make that a certainty.

Strategic summary

- The future economy will see rising demand for workers with advanced technical, cognitive and emotional skills.

- Policymakers in developed and developing economies alike need to boost education investment and underpin social protections.

- Investment in low-skilled workers would deliver the greatest overall economic rewards, creating a larger talent pool for companies.

- ‘Uberisation’ of the labour market in developing economies could boost transparency and reduce exploitation -- provided the regulatory landscape tightens.

- Collective bargaining in developed economies will decline further as workers migrate to the gig economy.

Analysis

Technological progress and automation of routine tasks suggest turbulence in the job market in the coming five years.

Risk of automation

400mn

Estimated job losses during 2017-30 in the worst-case scenario

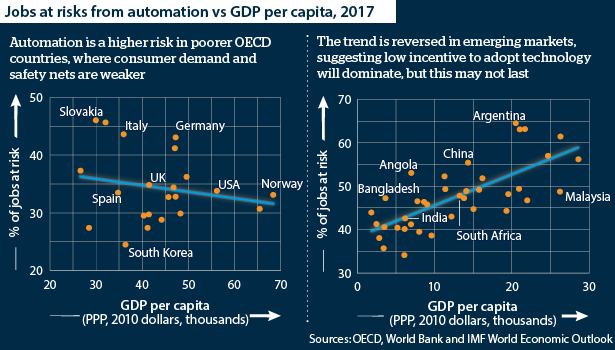

While most studies agree that the key risk factor for automation is per-capita income -- higher incomes raise the payoff to replacement by machines -- there are a variety of estimates for the actual number of jobs that are likely to be replaced over the coming decade in developing and developed economies.

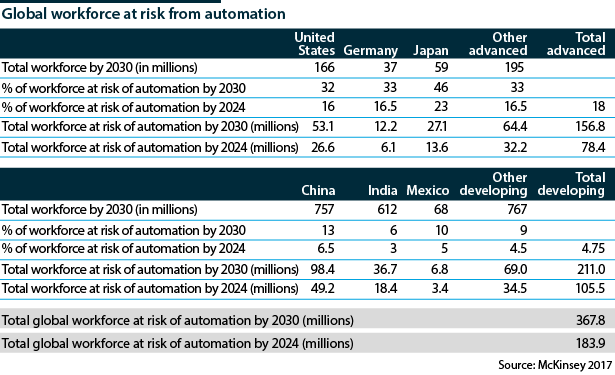

At the most alarming end of projections, or the worst-case scenario identified in studies thus far, is a 2017 McKinsey analysis of 40 countries comprising 90% of global GDP. It estimated that 184 million workers globally are at risk of job-displacement due to automation by 2024, and a total of 400 million during the period 2017-30.

Advanced economies

A 2017 study by Oxford researchers estimated that almost half of US employment is at high risk of being automated during the period 2026-36.

A different study took issue with this estimate, arguing that it does not account for the variety of jobs subsumed under the occupation-level data. Taking into account tasks such as planning, presenting or problem-solving, these researchers find only 10% of US jobs at high risk of automation.

The McKinsey study implies the number of US workers at risk of automation in five years is 27 million, or 16% of the workforce. This 16% figure applies across all advanced economies except Japan, where 23% of the labour force is deemed at risk.

Developing economies

106mn

Job losses in developing economies according to McKinsey's 2017-24 scenario

With lower per-capita income, the risks of automation for developing economies are lower.

McKinsey last year put this at 4.75% of the workforce in five years (ranging from 3% for India to 6.5% to China). This still results in more people being displaced by automation -- 106 million by 2024 compared to 78 million in the developed world.

Key concerns centre on the automation of manufacturing, which could hit workers whether applied within developed economies or via 're-shoring' of production processes closer to final markets in developed economies.

The precise impact of automation of individual developing countries will depend on their industrial and sector structures.

Industry structure

The International Labour Organization last year noted some developing countries feared that such re-shoring would wipe out their comparative advantage in labour costs. Vietnam, for example, indicated concerns for the re-shoring of textiles, apparel, footwear, electronics and electrical products.

Industry structure of specific developing economies will, therefore, determine the extent to which automation replaces human workers. Concentration in manufacturing, in particular, is associated with a greater risk of automation. Within manufacturing, a 2018 academic study noted, the risks are inversely proportional to the amount of intangible capital associated with the activity. For example, activities with a large intellectual-property component are associated with a lower risk of automation.

Nearly 12% of Malaysia's work activities, for example, are seen as at risk due to its unique concentration in mid-range manufacturing not characterised by intangible capital and intellectual property, whereas if per-capita income were the sole determinant, this figure would be closer to 8%.

Sector shifts

For the largest developing economies, a 2018 McKinsey report broke jobs down into more than 2,000 work tasks in 800 occupations to assess susceptibility to automation.

Replicating past trends of technological disruption in the labour market, the report found that the greatest shifts are likely to be in agriculture, with more and more workers moving out of the sector. The lower a country is on the income scale, the greater this shift will be, with India expected to see a six-percentage-point contraction in jobs in agriculture (as a share of all jobs) by 2024.

The Indian sector expected to grow most rapidly in terms of job-share is construction, with a shift from 9.3% of all jobs in 2018 to 13.1% by 2024.

In the advanced economies, jobs classified as having 'predictable' environments -- with routine or otherwise mappable tasks -- are at greatest risk of automation. McKinsey expects office support roles to see a 1.3 percentage point decline in total share by 2024, with other predictable-environment jobs losing as much as 2.1 percentage points.

Declining cost of technology

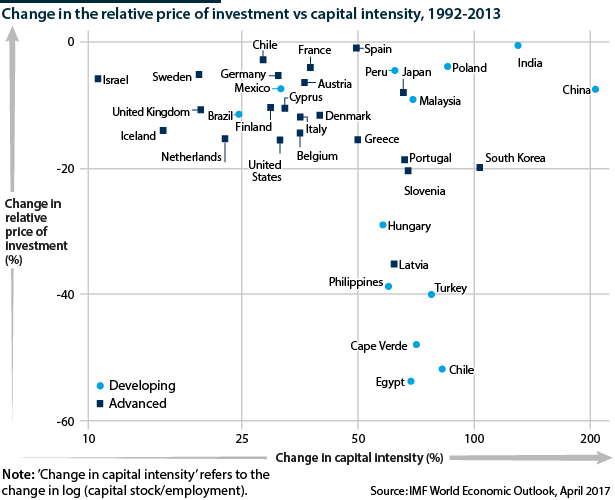

Technological advance -- loosely captured by the term 'automation' -- is not a prerequisite for creating the anticipated turbulence in job roles and functions; a decline in the cost of existing technology would have the same effect.

More affordable technology, especially information and communication technology, means more substitution of capital for labour, with damaging but even consequences for high- and low-skilled workers.

A 2018 IMF study estimates that a 20% drop in the price of capital goods (continuing the post-1980 trend for the United States, for example) increases income in advanced economies by 16% for high-skilled workers and by 7% for low- and medium-skilled workers.

Inflexion point

This is not to say jobs for low-skilled workers will not be created -- there will just be fewer of them relative to supplies of low-skilled labour.

This means that wage power will be commensurately lower in these occupations. Examples include low-skilled manufacturing and agriculture in developing economies, and office support workers and workers in the government sector in advanced economies.

A 2016 Cedefop study which used a forecast model of job types and took into account a moderate path of automation and digitisation, found an inflexion point in the sectoral allocation of jobs at 2015, in the interval 2005-25.

Focused on the EU-28 plus Norway and Switzerland, this study forecast a sharp deceleration in job growth for business managers and lawyers to around 1.2% overall growth during the period 2015-25, from 2.6% during 2005-15.

In line with other studies on advanced economies, this one forecast a contraction in clerical work (about 10% of the overall workforce) with one exception: customer service. The number of these roles is expected to accelerate, with growth of 2% in the 2015-25 interval.

Likewise, while plant and machine operator jobs are forecast to shrink, the sub-category of 'assemblers' is forecast to rise 2.3%. This is partly explained by the increasing human capital built into this job role, with higher skill-sets complementing higher automation.

Roles of the future

The 2018 McKinsey report tackles the question of automation from the point of view of workplace skills. These are broken down into sets such as social and emotional skills, technology skills, basic cognitive skills and manual skills.

The study's key conclusions are as follows:

- Technology skills should comprise about 14% of hours worked by 2024 in advanced economies. This runs from entry-level software use to higher programming skills.

- Social and emotional skills will be in greater demand as these cannot be substituted by machines in the foreseeable future. This encompasses, for example, leadership and managing others. Demand for these skills will grow sharply (by about 20% in advanced economies in the 15 years to 2030). These span innate skills such as empathy to learned ones such as advanced communication.

- Demand for entrepreneurship and initiative-taking will be even sharper, growing by around 33% in the 2015-30 interval.

- Relatedly, creativity will be another high-demand workplace skill rewarded by automation.

- Manual skills will still be the largest category of skill set, but they will see movement away from manufacturing and towards other sectors such as healthcare.

Particular opportunities for the developing world include skill shifts into 'leapfrog' technologies or those where greenfield development might be more practical or applicable than in developed economies. A 2017 World Bank study projected opportunities for biometric identification, drones for medical delivery and continued growth in business process outsourcing.

Re-skilling

Notwithstanding the variance in estimates for automation-related impact on the job market, the likelihood is that there will be significant churn in job roles in the coming five years.

While some jobs are lost to automation, many new ones will be created, leaving many mid-career workers with no choice but to re-skill or switch to new occupations.

Role of cities

Cities could be the new hyper-economic centres of the world

In previous bouts of productivity revolution, disruptions in the labour market were largely (although not wholly) resolved by sectoral and geographical shifts. Areas and sectors where jobs were being lost and where new ones were being created were clearly demarcated: broadly, (rural) agriculture lost and (urban) manufacturing gained.

These distinctions are less clear this time. An insightful projection about the next round of sectoral-geographical shift comes from economist Richard Baldwin, who argues that cities are to the 21st century what factories were to the 20th.

In a paper last year, he argued that the new shift would remain focused on cities but at a hyper level of attention. In his analysis, cities are a type of technology that reduces the cost of face-to-face interactions and optimise the matching between workers and work, and between suppliers and customers. This makes cities 'skill clusters' -- or as economist Enrico Moretti calls them, 'brain hubs'.

Baldwin sees urban policy replacing industrial policy in coming years, as urban areas allow workers in search of new roles to find the new roles in search of workers.

Social contract

Economic changes necessitate a new social contract between the state and citizens

Nearly all studies, whether focusing on the developed or developing world, agree that the future economy will prize advanced technical, cognitive and emotional skills. In turn, this consensus is driving the near-unanimity on the role of education in enabling workers at different skills levels to benefit from this transition (see INT: Redistribution is key to future of the workforce - May 25, 2017).

The 2018 IMF study mentioned above, is based on a general equilibrium model of an advanced economy. It finds that educational investment in low-skilled workers has the greatest positive impact in the presence of automation (see INT: Policy is key to curbing drivers of inequality - March 20, 2018):

- Relative to baseline levels of education spending, the higher-spending scenario boots low-skilled workers' income between 25% and 31% by shifting them into higher skill categories. Meanwhile, remaining low-skilled workers are scarcer, thereby boosting their wages.

- High-skilled workers' income is raised 9-12%, and middle-skilled workers' income 2-3%.

The cost of this educational intervention is estimated at around 2% of GDP.

Gig workers

To the extent that new technologies and processes mean a shift from highly formalised labour market engagements to more temporary and contingent forms of work, such as the 'gig' economy, there is a stronger argument for expanding the social contract to catch those whose workplace benefits disappear (see INTERNATIONAL: Alternative employment is rising - October 12, 2018 and see INTERNATIONAL: Platform work will outgrow policy - October 2, 2018).

A 2018 World Bank study suggests the opposite may be true for developing economies. Because so much work is already informal, the rise of 'gig' roles tied to larger employers or made more transparent by the associated technical platforms suggests a welfare increase -- via transparency and possibly collective bargaining (see INT: Women gig workers raise pressure for reform - September 17, 2018).

However, state regulation is critical to ensuring that these benefits materialise -- in key areas such as legally categorising gig workers as employees rather than independent contractors.