Autocratic rulers try diverse controls on social media

Social media by themselves promote neither democracy nor dictatorship; their impact depends on how they are controlled

Social media present both a problem and an opportunity for autocratic regimes. Such platforms create a public forum for dissenting views, but they also offer unprecedented opportunities to monitor and quash opposition. Closed political regimes have adopted different controls on social media.

What next

China’s approach makes it hard to avoid using state-backed social media, granting the state extensive surveillance powers and Chinese companies unprecedented economic opportunity. Compared with the confrontational approach pursued by states such as Russia and Ukraine, and managed controls of many Middle Eastern, African and Asian states, China’s approach is likely to be the most successful longer-term in using social media to extend state control over populations.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Access to China’s market requires political acquiescence.

- Smaller social media platforms will more readily assist surveillance.

- Encrypted services face rising surveillance pressures -- even from democracies concerned about radicalisation and disinformation.

Analysis

Non-democratic governments have diverse ways of controlling social media.

Direct pressure

One approach is legally to force platforms located within a country to give its authorities access to all personal data or risk being banned or taken over. This is the most direct and confrontational approach and followed most notably by Russia, where the state controls the market and law enforcement is political.

In 2016, Moscow enacted the Yarovaya law obliging all digital communication operators within the country to keep a copy of all messages (text, voice and images) from their users for six months, and their internet traffic for 30 days. This legislation was aimed at social media and mobile messaging apps and intended to expand state surveillance.

When popular encrypted messaging service Telegram refused to comply -- citing technical challenges and violations of Russian citizens' constitutional rights -- Russia attempted (unsuccessfully) to ban the service. The authorities are now testing a new monitoring technology called 'Deep Packet Inspection' which -- if successful -- could analyse all internet traffic and block data flows on such encrypted platforms (see RUSSIA: Telegram crackdown tests censorship limits - May 11, 2018).

A similar pattern occurred with VKontakte (VK), the largest and most popular platform in Russia with over 41 million active users. In 2014, VK CEO Pavel Durov (also the founder of Telegram) was forced to give up control of the company to investors allied with President Vladimir Putin after refusing to hand over personal user details. Under its new leadership, VK widely shares user details with the state, becoming an important tool for monitoring, controlling information flows and state propaganda.

This approach is working for now, but users are likely to shun these platforms longer-term or to use them only for benign activity, relying on alternative channels for political or sensitive communications.

Block access

Ukraine blocks Russian social media

An equally direct approach is to ban platforms deemed unfriendly to state interests. This approach has been adopted by states such as North Korea and Ukraine.

For example, Ukraine recently banned the two largest Russian social media platforms -- VK and Odnoklassniki (OK) -- along with mail.ru and Yandex ('Russia's Google'). Kiev called this a national security precaution justified by Russia's use of the social networks to spread propaganda and collect Ukrainian users' data. The ban is also part of Ukraine's overall pivot to the West. However, for ethnic Russians in Ukraine, this ban is akin to censorship: it stops them from communicating with family and friends in Russia.

Despite the crackdown, 11% of Ukraine's population still accesses VK (7.2% for OK) through the use of virtual private networks or proxy servers, compared with 36% using Facebook.

Future responses will likely attempt to balance cracking down on Russian-owned platforms, while trying to avoid the appearance of closely regulating the internet like Russia does. Such censorship will never be full-proof as technologies to bypass centralised internet restrictions are continually improving and becoming easier to use.

Tolerate but track

The UAE favours controlled use over outright bans

Another popular control tactic is to tolerate foreign social media and closely monitor public activity. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) practices this approach, as does Saudi Arabia (see SAUDI ARABIA: Riyadh will curb Twitter criticism - November 23, 2018).

The UAE has the highest social media usage in the world, with 99% of citizens online. Facebook is the most popular platform, along with its messaging platform WhatsApp (used by 82% and 83% of its citizens respectively). There is little evidence of direct state censorship of the platforms. Instead, the UAE has created restrictions on what is acceptable on social media, violations punishable with deportation or fines.

This strategy fits with the UAE's desire to attract foreign firms and talent, while controlling domestic dissidents.

This approach will likely become more difficult to sustain as Facebook reduces the amount of data available publicly.

Control through costs

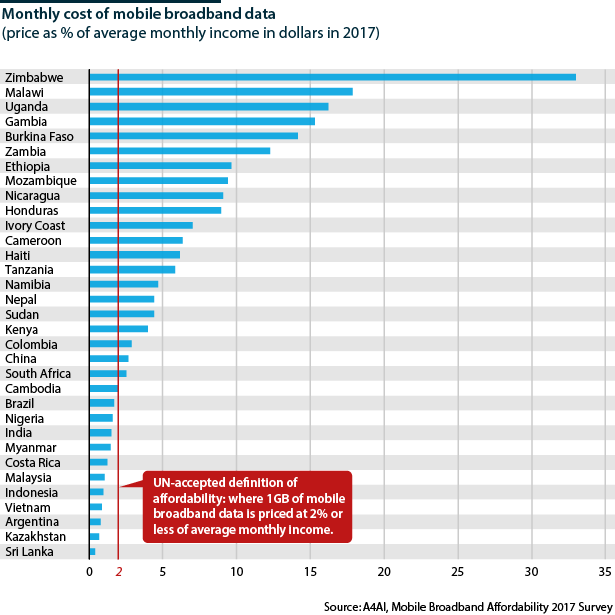

An alternative method -- adopted by African states such as Uganda and Zimbabwe -- controls social media use by increasing access cost (see UGANDA: Social media tax furore may simmer on - July 26, 2018).

In Zimbabwe, changes in technology have altered the media landscape, which was long controlled by the state and biased towards the ruling ZANU-PF party. However, with 50% of the population now online (primarily through mobiles), it has become easier to bypass state-controlled media, and social media are becoming a critical method of information consumption and political messaging.

The state sought to control social media by increasing the cost of mobile data, but later dropped the price and launched a mobile app from the President's Office.

Cuba rolled out long-awaited mobile 3G internet for the first time on December 6, but at a monthly cost equal to that of the state wage (30 dollars per month). Whether such pricing is a deliberate attempt to restrict access to the technology or not, the effect will be the same -- use will be severely limited unless and until prices drop.

Such direct forms of access manipulation are unlikely to prove successful in the long run as technology continues to evolve, pushing costs down, and access opportunities proliferate.

Trade cooperation with market access

A more market-driven and subtle approach consists of giving platforms access to lucrative markets in exchange for compliance with censorship requirements.

This approach has been followed in China and Indonesia with the Japanese platform LINE, which allows users to exchange texts, images, video and audio calls, and boasts over 70 million active monthly users in Japan and over 100 million users in Indonesia, Thailand and Taiwan.

LINE censors information: blocking messages relating to the Tiananmen Square protests and controversies about Tibet in China and references to homosexuality in Indonesia.

This case shows that smaller social media companies wishing to compete with larger platforms may be able to gain market share in authoritarian regimes by conforming to censorship in ways larger firms would be reluctant to accept.

Platform-state cooperation

Another approach consists of systematically favouring certain domestic companies and giving them an unfair advantage over market competition in return for long-term partnerships and compliance on surveillance. This approach is used most effectively by China (see CHINA: New laws advance 'cyber sovereignty' - September 29, 2017).

This approach has worked for WeChat -- an all-in-one messaging, shopping, gaming and financial services app developed by China's Tencent. It has over 900 million daily users and is used by 83% of Chinese with a smartphone.

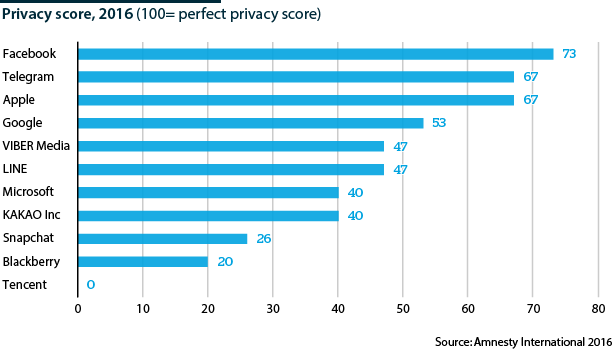

WeChat is reportedly used for state surveillance, including monitoring of conversations, images and even deleted messages. Western governments have banned officials from using WeChat.

A telling recent example of how close the state-corporate partnership has become is a pilot programme for WeChat to host an 'electronic ID card' that can be used in place of the physical identity cards issued by the state.

Even with a business model that could compete against Chinese companies, Western firms are unlikely to break into China's social media market without acquiescing to censorship; something Google CEO Sundar Pichai yesterday indicated his firm would in effect be willing to do.