Gender gap in workforce needs a multipronged approach

Improvements in narrowing the workforce gender gap are not keeping pace with global commitments on gender equality

Globally, women remain much less likely to participate in the labour market than men. This is despite the dampening effect of low female labour force participation (LFP) on global GDP.

What next

Globally, improvements in women’s LFP are expected to stagnate or even reverse through 2021. This could nullify past progress in lowering barriers to women's access to labour markets, besides depriving the global economy of talent and new growth potential. Women’s disadvantage could rise as technological evolution alters the structure of the global economy and future of work.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Investment in care industries would substantially increase women’s LFP.

- Flexible work that removes distortions against part-time work will enable firms to retain and cultivate female talent.

- Corporate pledges to achieve gender parity in their workforce exceed their policy initiatives.

Analysis

Women's global LFP rate stood at 48.5% in 2018 -- 26.5 percentage points (pp) below that of men, according to International Labour Organization (ILO). The ILO expects the rate of improvement, which has been slowing since 2009, to halt or even reverse over 2018-21.

The gender gap in LFP rates is narrowing in developing and developed countries; it stands at 11.8 and 15.6 pp in 2018, respectively. However, it continues to widen in emerging economies: it stood at 30.5 pp in 2018, up 0.5 pp since 2009, according to ILO data. The share of women in informal employment in developing countries is 4.6 pp higher than that of men.

The ILO forecasts that if gender LFP gaps moved halfway towards the median gap across countries in the EU and North America, global GDP could grow by 1.6 trillion dollars in purchasing power parity terms.

Interventions that work

Interventions that increase women's time and opportunity to undertake paid employment have proved effective.

Parental leave

A 2011 study shows parental leave, which allows both men and women to undertake childcare, reduces the gender gap in LFP by making women no more of a liability to firms than men.

The trend can reverse at the 140-day mark: very lengthy maternity leave can hinder women's LFP by discouraging employers from hiring women in the first place. It also adversely affects women's labour market skills from delayed absence -- in turn lowering their earnings.

Providing maternity leave without paternity leave (or non-transferable paternity leave) is likely to increase the childcare responsibilities for mothers while also reducing their long-term earnings relative to fathers.

Men's take-up rates are much higher where paternity leave is non-transferable, for example in Iceland where fathers averaged 39 days of leave in 2001 and after non-transferable leave was instituted the number of days rose to 103 in 2008, data show.

Men's take-up of paternity leave is higher in Sweden (90%) where it is non-transferable, compared to Denmark (24%) where it is transferable.

Care infrastructure

Female workforce participation rises as the cost of unpaid care work falls

Women globally do more unpaid care work: across 66 countries, representing two-thirds of the global population, on average women spend 3.3 times as much time as men do on unpaid care, according to a 2016 ODI study. This work is not recorded as economic activity in labour statistics.

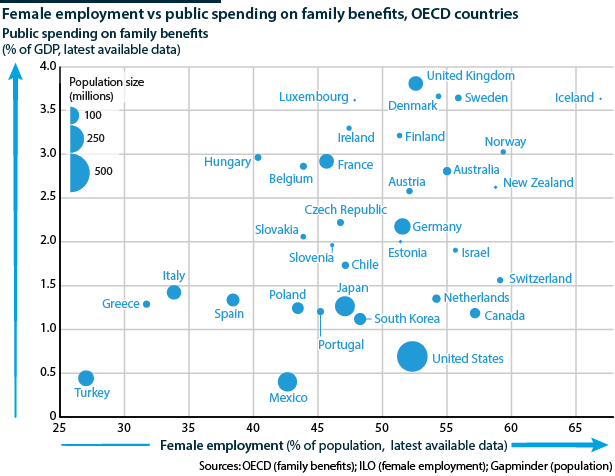

Female employment is higher in countries with higher public spending on family benefits.

In line with this trend, a 2016 analysis by the International Trade Union Confederation, based on a study of seven high-income OECD economies (Australia, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States), argued that 2% of GDP invested in the care industry (ie, for children, the elderly or the disabled) would lift overall GDP between 2.4% and 6.1% depending on the country.

Women's employment rate would increase 3.3-8.2 pp (and by 1.4-4.0 pp for men), and the gender gap in employment would be reduced by between 50% in the United States and 10% in Japan and Italy.

Flexible working

Policies that make flexible work available to men and women boost female participation.

Fixed office starting times set by an employer indicate inflexible working practices, the rigidity of which may conflict with the varying and changing needs of women, men and households, according to a paper by the Institute of Public Policy Research.

Options that fail to extend beyond the availability of part-time work -- if that is the main flexible working option -- may contribute to low average working hours among mothers during the early stages of parenthood as well as during subsequent life-phases.

While working part-time can reflect preferences, the high share of part-time employment may be a consequence of:

- shortage or affordability of care services (notably childcare);

- unequal division of unpaid work; and/or

- low financial incentives of full-time work.

For example, European Commission studies have shown that the employment rate of women with children younger than six is around 20 pp lower than that of women without children.

Making matters worse, working part-time is generally associated with lower hourly pay and longer-term earning potential.

Friendly taxation

Disadvantageous taxes on second earners adversely affect women

Second earners in married couples in most OECD countries are taxed more heavily than single individuals, depressing female LFP.

For example, a 2016 study showed that in countries where second earners are taxed more heavily, female LFP is low (eg, in Belgium, Slovenia and Luxembourg) while in countries where second earners are taxed comparatively little in the international context, female LFP is high, such as in Switzerland, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

Tax systems affect work-sharing decisions among couples in a setting where gender norms dictate women bear the burden of childcare.

Basic facilities

Affordable labour-saving consumer durables and basic amenities contributed to raising female LFP during early industrialisation by easing the burden of domestic work, which is still disproportionately carried out by women.

These facilities have yet to reach all women. For example, in Sub-Saharan Africa -- where over two-thirds of the population lacks access to domestic tap water -- the time-consuming chore of collecting water outside the house falls primarily to women.

Training programmes

Training to fill the skills gaps that women face in gaining formal employment increases the probability of their employment. However, it rarely leads to increased earnings over the longer term without follow-up support. Women's LFP is limited by constraints on their time rather than solely skills.

Vocational training in low and middle-income countries has been shown to have small positive effects: overall employment and formal employment increase by 11% and 8%, respectively, and income by 6%.

Structural barriers -- eg, time constraints for participation, and economic and labour market barriers -- limit training programmes' effectiveness (see INT: Women gig workers raise pressure for reform - September 17, 2018).

Outlook

A 2016 ILO study documented a package of measures that worked together rather than in isolation to favour gender-equal labour markets. It included:

- parental leave, paid at a high level with sharing rights for both men and women;

- provision of affordable childcare;

- flexible work options to allow for two-earner households; and

- care credits for social protection to decrease the penalties for discharging unpaid care work.

Most countries have yet to undertake such a comprehensive approach.

Beyond workforce participation

Increasing women's LFP guarantees neither economic empowerment nor gender equality in the labour market. Sub-Saharan Africa has some of the world's highest female LFP rates alongside the highest rates of gender inequality and poverty.

Ensuring women's participation in the labour market and engagement in 'decent work' that is (among other things) sustainably safe and paid fairly has proved challenging.

National pledges on the UN sustainable development goal of gender equality far exceed policy action (see INTERNATIONAL: UN's development goals need new allies - November 15, 2018).