Digital currencies enhance 21st century monetary tools

Digital currencies could give central banks a potent weapon in the fight against deflation

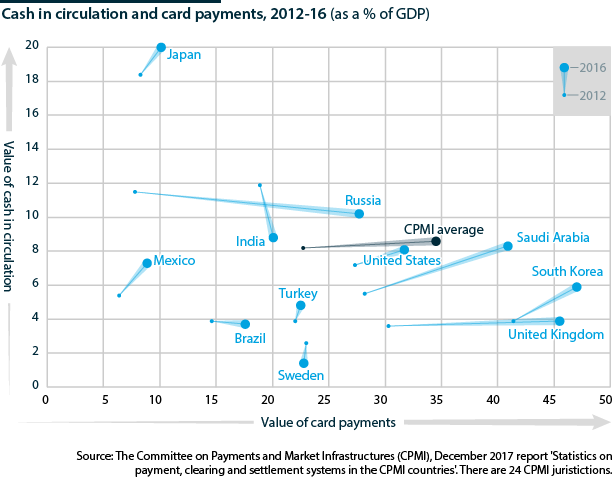

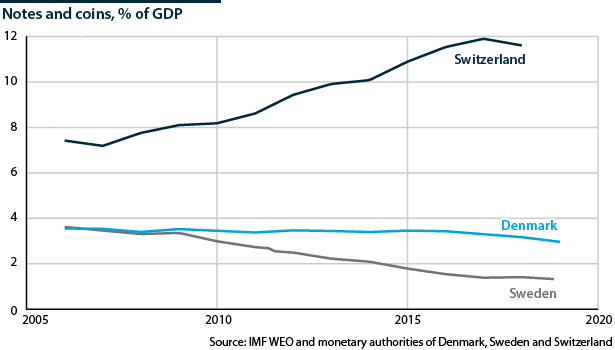

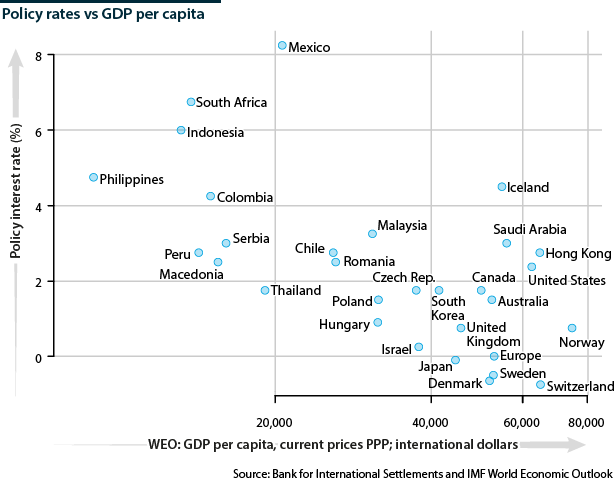

With the use of cash dwindling in the advanced economies, central banks are losing their only direct monetary connection to the public. At the same time, monetary policy could face meaningful limits in stimulating growth if a severe recession strikes the advanced economies as policy interest rates are already close to zero.

What next

Once the structures are in place, the step towards using state-backed digital currencies to fight deflation is small despite it currently being ignored or dismissed as fanciful. The key caveat is legal authority. Central bank mandates could in theory be modified to preclude such usage.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Tech advances, combined with downgraded long-term growth, price and interest rate forecasts, draw attention to new monetary policy tools.

- Central bank digital currencies would have a central custodian to coordinate them, overcoming a key ‘stateless’ cryptocurrency weakness.

- A digital currency gives central banks a way to reflate the economy and support certain households, but there may be political obstacles.

Analysis

Calls for central banks to consider issuing 'digital money' seem esoteric at best. 'Money' works so well we have long since stopped worrying how it comes about. There seems little to fix.

Moreover, one might argue that digital state currency already exists in the form of the public's deposits in commercial banking. On the internet, these are interchanged regularly without even a bank draft (cheque) or transformation into physical cash.

Additionally, these deposits are incredibly stable. They almost always carry some form of deposit insurance scheme backed by the state. They also trade equivalently to cash, in the sense that bank deposits can usually be converted into cash without a fee. Current-account services are usually free, rarely generate interest, and sometimes even cost the depositor a monthly fee. None of this indicates anything inferior to state money.

Bank money

However, distinctions emerge. Banking deposits are not state money, let alone digital state money. Officially 'bank money', they are liabilities of the banking system -- not the state, except for the amounts within the deposit-insurance scheme.

Institutional money managers keep large sums of liquid assets in government bonds -- liabilities of the state -- rather than bank deposits, no matter the interest rate being proffered.

Yesterday's war

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the state sets limits on how much bank money can be created by requiring banks to hold a minimum of state money ('reserves') against public deposits (the 'reserve requirement'). This is designed to fight yesterday's war -- inflation. It has nothing on today's worry: deflation.

Monetary base

Actual state money (the 'monetary base') is a state liability consisting of two parts: the banking system's deposits at the central bank (reserves) and cash in circulation.

If policymakers want to put money into the hands of those most likely to spend it (and stimulate the economy and ward off deflation), taxation is their only means. The government could credit people's bank accounts with a transfer from the tax authority.

One drawback is the political capital needed to pass it through legislative and governmental frameworks. An equivalent power on the part of the monetary authority would be quicker (albeit less democratic -- although the same can be said of monetary policy generally).

Pushing on a string

The reserve requirement is useful for reining in credit creation (and therefore the amount of bank money in use), but useless at cajoling the banking system to create more credit. John Maynard Keynes likened monetary policy in a deflationary environment to 'pushing on a string'. It is designed for the 1970s (or 1920s) rather than the 20th century.

Using monetary policy to stimulate activity in a deflationary environment is like 'pushing on a string'

Digital money

If it becomes desirable to give the central bank the means to put money into people's hands, state-sponsored 'digital money' might fit the bill. It would give monetary policy a more effective means of warding off deflation or fighting a recession, if policy interest rates are already at zero and demand for credit is scarce.

Unlike cryptocurrencies, state-backed digital currencies could be issued flexibly at the discretion of the monetary authority, giving it another policy tool. In most cases, these currencies would be treated as equivalent to cash; they would not compete with cash per se.

State backed digital currencies could be flexible and would largely be treated by the public as equivalent to cash

Crypto lessons

Perhaps one of the greatest learnings from 'cryptocurrencies' is the utility of a central player in coordinating any currency system (see INTERNATIONAL: Multilateral crypto oversight will rise - February 19, 2018). Cryptocurrencies lack any such central coordinator or custodian (they are designed to be stateless).

The difficulty of designing a system which balances public availability with a stable value is a key weakness.

Bitcoin's key attribute was its mechanism for monetary expansion without a central authority (Bitcoins can be 'mined' up to an ultimate maximum) (see INT: Bitcoin 2017 prospects - January 16, 2017). Yet Bitcoin's swings are notorious, as are some of the security breaches and the amount of electricity the mining consumes.

Central banks

More than one-third of the 63 central banks responding to a 2018 Bank for International Settlements survey said it was "possible" they would issue a digital currency within six years. Of these, about one-third said very likely or somewhat likely.

>1/3

Central Banks that see themselves issuing a digital currency

Central banks are getting more confident of their legal authority to do so. In 2017, over 60% were uncertain of such authority. That proportion dropped to 40% in 2018, with the certainty falling evenly between understanding that they do not have the authority and understanding that they either do have the authority or are aware of laws being changed to allow it.

Vanguard?

The public's use of central bank money is limited to physical cash. With cash usage shrinking, Sweden's central bank, the Sveriges Riksbank, is investigating issuing an 'e-krona', creating a state digital currency via public deposits with the central bank or via a card pre-loaded with e-krona.

Both routes have strengths and weaknesses, and the bank's research recommends further exploration before realising either.

Policy paradox

Nowhere does the Riksbank cite fighting deflation as a motivation for the project.

This points up a paradox in the implementation of such currencies.

Developing countries by some measures provide the most fertile grounds for uptake as their usage of cryptocurrencies and innovative monetary platforms generally exceeds that of the developed economies (see INTERNATIONAL: Digitalisation to divide and drive GDP - July 17, 2018).

Advocates also cite less trust in traditional banking in some developing countries, but trust can be bolstered in several ways from deposit insurance to avoiding banks entirely. Digital currency will face the same security concerns as traditional banking.

The paradox comes from developing countries having arguably the least need to fight deflation. Developed countries have more to worry about in terms of a limited policy toolbox but might be less eager to take up these currencies (see INTERNATIONAL: Participation and productivity are key - October 19, 2018).

The Riskbank is an unlikely institution for this, having erred on the side of excessive caution since 2008-09.

It cites other motivations for exploring the e-currency (apart from the dwindling use of physical cash and thus loss of monetary connection to the public).

These include the ability to preserve payments in time of crisis (assuming the central bank's platform is more stable than the banking system's) and the ability to offer a level playing field for innovators to offer the public services.