Global anti-corruption efforts face new obstacles

The growing emphasis on national sovereignty risks progress on global anti-corruption efforts

'Fighting corruption' has become a staple of political debate across most low- and high-income countries. However, the prospects for the success of national and international efforts are modest.

What next

Anti-corruption will top political agendas in most countries, but reforms will be partial and progress incremental. Although the international capacity to tackle corruption is improving, the will for global action is weak, marked notably by limited appetite at the OECD level, the current US administration's aversion to multilateral cooperation and China's lack of interest in attaching transparency conditionalities to its foreign investment.

Subsidiary Impacts

- A second term for US President Donald Trump term would advance Washington's retreat from promoting anti-corruption overseas.

- China's Belt and Road Initiative is plagued by opaque deals.

- Western corporates are likely to strengthen anti-corruption efforts for legal, financial and reputational reasons.

Analysis

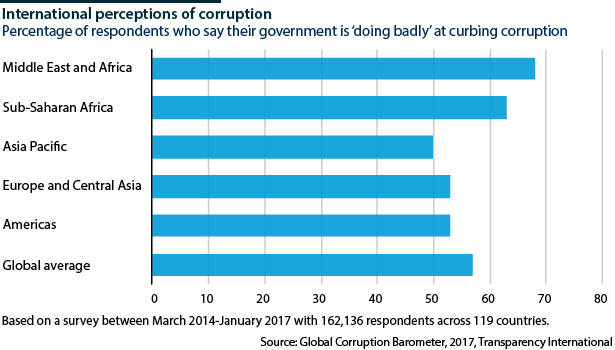

Every two years Transparency International (TI) publishes a 'Global Corruption Barometer' (GCB) which is based on a poll of over 150,000 people worldwide. In the 2017 survey, 57% of the respondents said their government was 'doing badly' on fighting corruption.

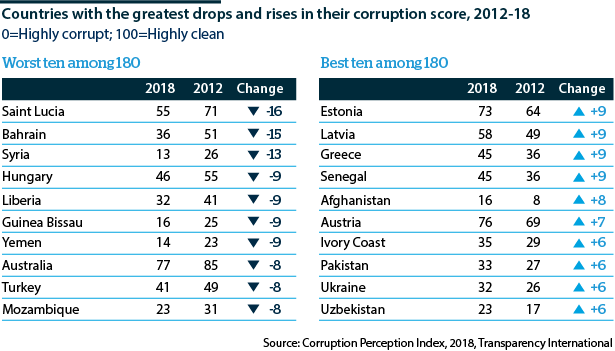

The TI's 2018 'Corruption Perception Index' (CPI) was released in January. It measures perceptions of bribery and other forms of corruption at the interface of the public and private sector.

It points to relatively small improvements since 2012:

- The score of the worst performer, Saint Lucia, fell 16 points to 55 out of 100 between 2012 and 2018. The best performer, Estonia's, score only rose by nine to 73.

- Denmark received the highest score (88) despite the Danske Bank scandal, and Somalia the lowest (10).

Similarly, World Bank surveys on the 'Control of Corruption' during 1996-2015 showed that only eight of 214 countries had achieved an improvement of 20 points or more on the survey's basic criteria.

Even though quantification and definition of 'corruption' at the national level is difficult and controversial, these surveys underline that corruption is perceived to be pervasive.

Corruption: different and same

Political campaigns focused on anti-corruption feature both common ground and differences. Differences are focused on specific circumstances:

- In resource-rich countries such as Nigeria and Indonesia, anti-corruption rhetoric focuses on the plunder of these resources for personal gain.

- In Brazil recent corruption scandals focus on the political misuse of resources of state-controlled Petrobras, and bribes paid by construction company Odebrecht across Latin America.

- In South Africa the focus has been on 'state capture' by influential business families.

Yet such campaigns have much in common: the role of political elites in self-enrichment, the policy influence of financial backers of political parties, and the role of public servants in extracting low-level bribes.

National efforts

National anti-graft efforts must navigate complex local dynamics

Political campaigns that do not focus on anti-corruption are limited to a few OECD countries (eg, the United Kingdom) and a few outliers with an exceptional history (eg, Singapore). Several leaders have risen to power on an 'anti-corruption ticket', most recently in Mexico, Brazil, Malaysia and Pakistan. Yet none of the leaders has effective strategies.

Mexico

President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) has vowed to reduce corruption that plagued the governments of his predecessors Enrique Pena Nieto and Felipe Calderon.

While AMLO has cancelled construction work on a new airport and cut public sector salaries (citing corruption in both cases), his administration lacks a convincing approach to controlling Mexico's drug cartels, which co-opt politicians at the provincial level (see MEXICO: Crime strategy risks repeating past mistakes - January 28, 2019).

Moreover, his administration will not pursue corruption investigations against its predecessors.

Brazil

President Jair Bolsonaro's anti-corruption proposals includes stiffer sentencing, requiring those convicted of corruption to begin serving their sentence after it is upheld on first appeal (rather than three appeals as previously) and criminalising the use of undeclared campaign funds.

However, such measures cannot hope to dismantle the complex system of political fixing that is linked to Brazil's corporate world, and reforms may be resisted in a Congress where many face corruption cases. Indeed the president's son, Senator Flavio Bolsonaro, is facing corruption probes (see BRAZIL: Bolsonaro has momentum, but faces pitfalls - February 11, 2019).

Malaysia

Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad's government is pursuing corruption cases against his predecessor Najib Razak Najib and the notorious 1MDB case in courts. Elsewhere its efforts are narrow: they focus on cleaning procurement and bribery of mid-ranking civil servants (see MALAYSIA: Autocratic governance will increase - August 16, 2018).

Pakistan

Prime Minister Imran Khan, whose political rise is based on his anti-corruption campaign, has prioritised repatriation of illegal financial assets held abroad, and promised a whistleblower system for the public and private sectors.

Yet foreign countries that act as havens for such assets have limited incentives to cooperate, whereas whistleblowing is ineffective even in robust law-abiding countries, which Pakistan is not.

International cooperation

The frameworks for fighting corruption through international cooperation have improved over 25 years (see INTERNATIONAL: Anti-corruption capacity is improving - July 10, 2018).

Notably, the bribery of officials in a foreign country whether by individuals or companies has been criminalised by all 34 OECD members by national laws such as the 1977 US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) and the 2012 UK Bribery Act.

The UN Convention Against Corruption signed in 2000 by most UN member states supports a range of measures including the repatriation of corruptly gained assets.

Money laundering is also under unprecedented scrutiny, especially the role of tax havens and offshore centres:

- Measures against shell companies that disguise their 'beneficial ownership' have been embodied in legislation in the United Kingdom.

- EU's Fifth Money Laundering Directive is due to be fully effective by 2020.

- Similar measures may be adopted by the US Congress (where draft legislation has bipartisan support) in relation to US states that allow the obscuring of corporate beneficial ownership.

Such institutional efforts have traction among corporates as reflected in the:

- UN Global Compact, which has brought together over 9,000 firms voluntarily to advance Sustainable Development Goals, one of which is reducing corruption; and

- codes of business conduct by the International Chamber of Commerce and the World Economic Forum.

Yet the effectiveness of these institutions and initiatives is in jeopardy amid growing emphasis on national sovereignty at the expense of international obligations.

Weak transnational action

In its 2018 report on the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, TI found the seven countries that were 'active enforcers' had themselves brought only eight major cases of foreign bribery to court in 2017. The picture among 'moderate' and 'low' enforcers is even poorer, with no cases being brought in 2017 by either Japan or India.

International cooperation on investigations through Interpol has been eroded by the arrest by China in October 2018 of Interpol Director-General Meng Hongwei.

US ambivalence

Congress may succeed in ending 'beneficial ownership' regimes, and the Department of Justice is continuing its probes under the FCPA regardless of President Trump's views; before taking office, Trump described the FCPA as "a horrible act".

However, due to the lack of interest shown by the current White House and the president's own controversial personal business dealings, the US administration has lost credibility as an advocate of global anti-corruption efforts.

China's narrower focus

China's anti-corruption efforts are enitrely domestic

China is not at the forefront of such efforts.

Its Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank has explicitly rejected adopting Western multilaterals' concerns for transparency and social values (though it is more accommodating on environment).

President Xi Jinping's anti-corruption drive is exclusively domestic; it does not extend to projects financed by China overseas, notably as part of the Belt and Road Initiative.

China has not signed the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention although it is open to non-members.