Mexico’s domestic policies jeopardise economic growth

The president’s policy decisions have sparked fears among investors

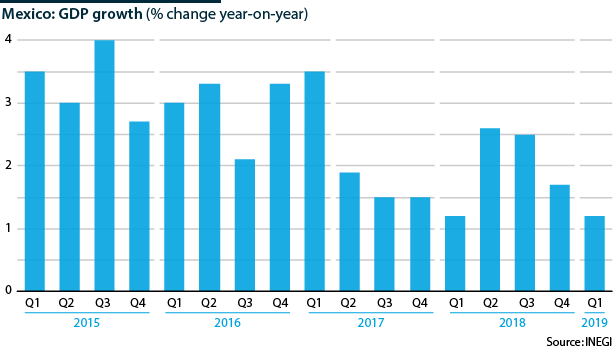

Mexico’s economy took an unexpected plunge during the first quarter of 2019, contracting by 0.2% quarter-on-quarter. The slowdown is becoming more widespread amid declines in industrial production and services. All major international financial institutions, the Bank of Mexico and even the Ministry of Finance have slashed their growth forecasts for this year to around 1.6%. President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO)’s promise to achieve an average annual growth rate of 4% over his six-year mandate -- more than double Mexico’s sluggish average rate for the last decade -- is looking increasingly unobtainable.

What next

Mexico’s economic prospects are gloomy. Uncertainty surrounding the future direction of public policies, the evolution of the oil sector, delays in ratifying the US-Mexico-Canada trade deal and US tariff threats are tilting the balance of risks to growth to the downside. Despite the approval of a reasonable budget, fiscal accounts will likely weaken on the back of poor economic growth and fiscal relief measures to state oil firm Pemex, in turn threatening Mexico's sovereign creditworthiness.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Risk of a US-Mexico trade war has seen peso depreciation and, if sustained, will hit investment and inflation, ultimately harming growth.

- Public spending cuts will hit investment projects, with private investment, hampered by falling confidence, unlikely to fill the gap.

- AMLO’s energy policy may weaken the finances of Pemex; downgrades for both Pemex and the sovereign cannot be ruled out.

- Inflation risks remain to the upside, mainly due to peso weakness and wage pressures, reducing the chances of an early rate cut.

Analysis

AMLO's promise to double the pace of economic growth is off to a rough start. The 0.2% contraction in the first quarter was worse than any estimates, while in annual terms, output grew at 1.2%, its slowest rate of growth in a year.

0.2%

Contraction in the first quarter of 2019

On the supply side, industrial production fell for the third time in five quarters (down 0.6% on the previous quarter), and services, which have been the main engine of growth in recent years, declined by 0.2%. In contrast, the primary sector registered 2.6% growth.

As regards demand, while exports showed an upward trend, private consumption is losing steam, and investment has declined.

In this context, several factors are worth considering:

- Sluggish growth in the first year of a new administration is not uncommon, as officials struggle to make public spending flow. New projects must be approved, with most set to be rolled out during the six-year mandate.

- Economic activity in early 2019 has been affected by short-term disruptions: petrol shortages in some cities, blockades to railways that connect different regions and seaports, and labour strikes along the northern border.

- On the international front, delays in ratifying the trade agreement with the United States, which accounts for around 80% of Mexico's total exports, have not favoured business confidence.

US President Donald Trump's recent threats to impose a blanket 5% on all Mexican imports from this month, rising monthly to 25% in October if Mexico does not prevent undocumented migration to the United States, smacks of populist rhetoric but is also damaging. While the 25% level will almost certainly never be reached, a tariff of even 5% could cause serious economic disruption.

Investor confidence waning

AMLO's decision to scrap a half-built 18-billion-dollar airport last December, based on a widely criticised referendum, raised concerns from the beginning of his mandate that he was inclined to tear up existing contracts, disregard the rule of law and weaken investors' confidence in Latin America's second-largest economy (see MEXICO: Airport stunt brings long-term risks for AMLO - November 12, 2018 and see MEXICO: Mixed signals will undermine business trust - March 6, 2019).

His intention to reverse some of the pro-business policies adopted by former President Enrique Pena Nieto is further undermining the business environment. Promising to revive Pemex, he has put the brakes on foreign investment in a professed effort to give Mexicans a bigger share of the country's oil wealth (see MEXICO: Government will strive to revive Pemex - December 19, 2018).

Oil auctions have been suspended for the next three years. The cancellation of the tender for the Dos Bocas oil refinery project last month (which had only been approved in January) is the latest example of the government's erratic policymaking process.

This is particularly worrying in Mexico where many planned projects rely heavily on private equity, given the government's limited ability to fund large-scale infrastructure projects. The value of private investment in Mexico is more than six times that of its public counterpart. Uncertainty surrounding policymaking will dissuade private investment, threatening infrastructure development over the coming years.

In fact, the IMF cited the backtracking on energy reforms as one of the reasons for its decision in April to cut Mexico's growth forecast to 1.6% in 2019 and 1.9% in 2020, down from January projections of 2.1% and 2.2%, respectively.

1.6%

IMF growth forecast for Mexico in 2019

Pemex puts pressure on public finances

Gradual tax cuts, to be spread over five years, and an 8-billion-dollar syndicated loan (of which 2.5 billion will pay off existing debt and 5.5 billion will replace several credit lines) have been announced to revive Pemex without tapping the Oil Revenue Stabilisation Fund.

These measures could help Pemex, whose 106.5-billion-dollar debt is the highest of any oil company in the world, stave off another credit downgrade (Fitch cut its rating to one notch above junk in January) and provide a much-needed liquidity boost.

$106.5bn

Pemex's debt

Ultimately, the government aims for Pemex to meet its investment plans without creating a burdensome situation for public finances.

However, this may prove unrealistic; infrastructure plans that have been announced are highly ambitious and risk cost and time overruns. AMLO intends to build a new 8-billion-dollar refinery and refurbish six existing refineries to run at about 90% of capacity (up from 35%) in just two years.

Mexico has been struggling to reverse a steady decline in its crude oil production caused by years of underinvestment. AMLO has promised that by the end of his mandate, Pemex will produce almost 2.5 million barrels per day (b/d) of crude, up from an average of 1.8 million b/d in 2018.

Moody's has already questioned the refinery decision, arguing it would probably take longer and could cost 50% more than planned. Pemex runs the risk of losing its investment grade, which could cripple the president's ambitious energy agenda, along with his plans to use new oil revenue to help finance social welfare programmes without tax increases.

Ratings agencies have also highlighted overall concerns about the Mexican government's spending plans and debt load, thus menacing Mexico's sovereign creditworthiness.

Strong economic fundamentals

Mexico's credit risk is mitigated by its positive macroeconomic fundamentals:

- Both government debt and external debt are sustainable, with the latter having stabilised to a relatively low 40% of GDP.

- Current account imbalances remain modest (1.8% current account deficit in 2018) and have so far been comfortably covered by foreign direct investment.

- Foreign exchange reserves cover around four months of imports.

- Access to a precautionary IMF credit line of 74 billion dollars (until November 2019) provides a cushion for potential adverse global credit conditions.

While such buffers reduce Mexican vulnerability to any upswing in risk aversion, however, AMLO's handling of major national projects is far from helpful in encouraging investment, a key element in stimulating economic growth.