Prospects for Syria in 2020

Syria is dominated by foreign powers allied with local factions, of which the government is by far the strongest

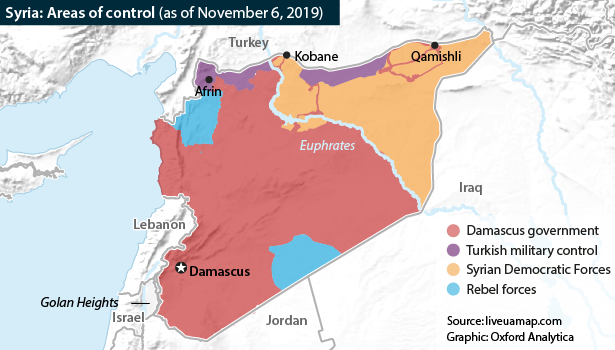

US policy shifts have benefited Damascus, Moscow and Ankara at the expense of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), and undermined Washington’s influence. The government of President Bashar al-Assad now faces no serious military threat. Although it is recovering territory, it cannot govern it effectively, and discontent among its Alawi base is rising. Idlib remains contested. Some 11 million Syrians are refugees or internally displaced.

What next

The government and Turkey will split northern Syria at the expense of Kurdish-led forces. Population transfers, displacement and criminality are likely. Governance and the economy will remain weak in the absence of an improbable, internationally-backed political settlement, fuelling discontent, including in loyalist circles. Although some US troops appear likely to remain in Syria, US influence will be limited and a complete withdrawal remains plausible. Israeli strikes on Iranian assets, government operations in Idlib province and a low-grade Islamic State (IS) insurgency will persist.

Strategic summary

- Assad will reject meaningful political compromise with all opposition, ensuring Syria's isolation, economic stagnation and popular discontent.

- Most refugees and internally displaced Syrians are unlikely to return, except for some moving into Turkish-controlled regions.

- The US military presence will not affect the strategic outlook, and moreover remains tenuous.

- Israeli attacks on Iranian operations pose a moderate risk of escalation between Hezbollah and Israel in Lebanon.

- Government forces will make slow advances in Idlib.

Analysis

A clearer, more durable balance of power between foreign powers is emerging, with Damascus, backed by Moscow and Tehran, holding the bulk of the country; a Turkish-influenced zone in the north; and a possible residual US presence in the east. However, this carve-up will not address the core drivers of conflict, including poor governance, repression, ethno-sectarian tension, economic decline and the refugee crisis.

Government areas

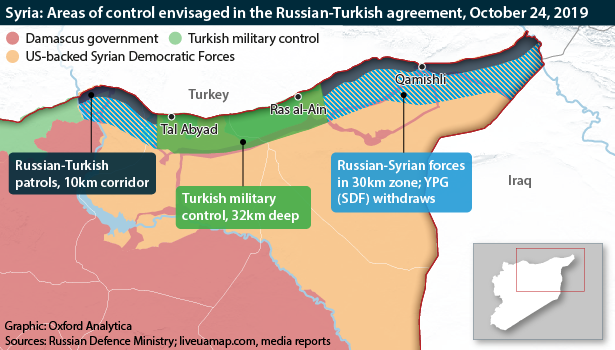

The Assad government no longer faces any serious insurgent threat. It will benefit from the US withdrawal from northern Syria and a Russian-Turkish agreement that grants it substantial territory and de facto legitimisation by Ankara, after the years it has spent fighting Turkish-backed rebels (see RUSSIA/SYRIA: Opportunism advances Russian aims - October 24, 2019).

Allies Russia and Iran will provide enough support to maintain the security apparatus and contain military opposition, given their own interests:

- Moscow will largely take over the Syrian file from Washington, growing closer to Ankara and acting as a mediator and guarantor between Turkish, Kurdish and government interests.

- Tehran will focus on combating Israel and protecting supply lines to Hezbollah in Lebanon, keeping control of a land bridge that runs through Iraq, the lower Euphrates River valley and the Syrian-Lebanon border area between Damascus and Homs.

However, these partners cannot and will not rebuild Syria's economy. That would require resources from the United States, Europe or the Gulf Arab states -- which would be conditioned on political reforms that the government will reject (see EU/SYRIA: Internal EU divisions will emerge over Syria - April 2, 2019).

Syria will therefore remain poor and badly governed. Inflation, unemployment and corruption will drive public resentment among the government's traditional Alawi support base. This is increasingly likely to give rise to civil unrest.

11mn

Estimated Syrians unable to return home

Some five million internally displaced Syrians across the country and around six million refugees abroad are unlikely to return in large numbers to government-held territory. They are concerned about the lack of rebuilding and economic opportunities, property disputes, conscription and government reprisals.

Both Kurds and Arabs in areas that have recently returned to government control after the US withdrawal may face suspicion and repression, with little protection. Although the SDF was an excellent light infantry force against IS, it lacks artillery or air power, limiting its capacity to oppose Damascus and its allies unaided -- especially given the simultaneous threat from Ankara.

Turkish zone

In 'Operation Peace Spring', by invading northern Syria following a US decision to withdraw, Turkey has achieved its primary strategic goal in the country: preventing the emergence of a US-allied Kurdish-led proto-state.

Ankara and its auxiliaries will control Afrin and a 32-kilometre-deep, 120-kilometre-long buffer zone agreed with Moscow. These areas will see increased trade and infrastructure integration with Turkey -- but also criminality and repression.

As it has pioneered on a small scale in Jarablus, Turkey intends to resettle some of its millions of Syrian refugees in these zones, even though most originate from elsewhere. Despite international resistance on human rights grounds, this is likely to go ahead, although possibly not for the numbers promised by Ankara. It will cause social disruption and possible forced displacement within the territories amid friction between Arab and Kurdish populations.

For Syria's former armed opposition groups, the only remaining safe haven will be in Turkish spheres of influence. Here they will be expected to follow Turkish orders and focus on fighting Kurdish forces rather than Damascus.

The fight for Idlib could bring back chemical weapons

The situation is slightly different in the northwestern province of Idlib, which remains under the control of militant groups including jihadists (see SYRIA: Turkey may narrow its aims in protecting Idlib - September 10, 2019). A limited Turkish presence will not deter government attempts to retake the area, but this will be a slow and costly battle. Lacking manpower and facing an experienced, well-armed adversary in difficult terrain, Damascus may again resort to chemical weapons.

US presence?

The United States' abrupt withdrawal from northern Syria and acquiescence to a Turkish ground invasion undermined its influence over both its Kurdish-led allies and its adversaries.

Washington has indicated it will maintain a garrison at Tanf airbase in the south-east, near the Jordanian border, and keep several hundred troops and armour in largely Arab areas east of the Euphrates River, ostensibly to secure the oil fields. The main aim is in fact to counter Iranian influence and its land bridge to Hezbollah in Lebanon.

However, supply lines will be vulnerable to Iranian disruption. The United States has no capable, cohesive partner in these areas equivalent to the SDF, which has distanced itself from Washington and is in any case far less committed to governing this territory than the areas it lost to Turkey.

US control in these areas will therefore not translate to influence over Syria's broader trajectory. Moreover, US President Donald Trump remains inclined to disengage from Syria completely, making the US presence tenuous.

The battle against Iran in Syria will instead be led by Israel, which is likely to launch further air strikes as it seeks to prevent Tehran's consolidation of a military presence or transfer of strategic weapons. That could potentially trigger an escalation between Hezbollah and Israel in Lebanon (see LEBANON: Hezbollah will avoid Israel escalation - October 16, 2019).

Meanwhile, IS, the original justification for the US intervention, is no longer a territorial entity that controls strategic resources or infrastructure. The death of its 'caliph', Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, together with the follow-up targeting of other senior figures, constitutes a significant blow to morale.

The group has little chance of rebuilding in the east while Washington maintains its forces. It will try to exploit violence, dislocation and the fragmentation of authority in the northern areas regained by the government to rebuild capabilities, free prisoners and recruit among aggrieved Sunni populations. However, it no longer poses a strategic threat.