East Africa locust control will require coordination

A major desert locust plague offers a stark reminder of the importance of prevention and international cooperation

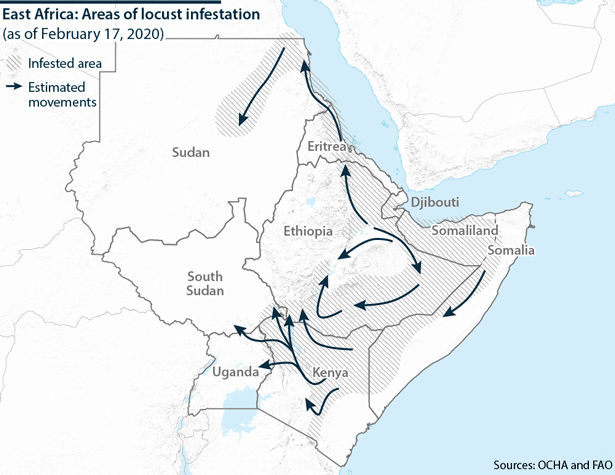

The worst desert locust infestation in decades currently threatens crops across several countries of East Africa, severely stretching regional response capacities. Prevention systems have failed and an international emergency response has been slow to mobilise. Without urgent international cooperative action at all levels, the situation could yet deteriorate further. Moreover, without serious efforts to strengthen preventive management systems, similar crises may recur.

What next

Ethiopia, Somalia and Kenya currently face a high threat of crop damage and new food security stresses over the next three months. If cooperative control measures are not implemented, other African and Middle Eastern countries may also become severely impacted. As actions are still not planned (or in some cases possible) in conflict-affected areas where swarms are currently breeding, the plague may persist over a long period, and could spread into West and North Africa. Over the longer term, climate change may heighten the risk of new infestations. Managing these risks will require sustained efforts to reconstruct preventive management systems in all locust-affected countries.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Unresponsive governments will face criticism for their lack of anticipation and action, though some simply lack the capacity.

- The long-term impacts will be particularly severe for smallholder farmers, accelerating the rural exodus and deepening urban poverty.

- Export-oriented agricultural production may suffer, including through losses of agreements due to large-scale pesticide use.

Analysis

Desert locusts are a species of grasshopper that are capable of changing behaviour from a 'solitarious' mode to a 'gregarious' swarming mode.

When they are few in number, desert locusts move around little, generally avoid each other and use camouflage to protect themselves. As their numbers multiply, this behaviour shifts dramatically and they transform into large, colourful, mobile swarms that consume all vegetation they can find.

Desert locusts naturally occur as solitarious from the west coast of Africa to India. They mostly inhabit semi-desert areas and take advantage of good rains that bring green vegetation and good soil moisture for breeding.

If rains fall where natural predators are absent because of aridity, desert locusts may multiply by a factor of more than 20 in one generation. This multiplication leads to an increase in insect density and eventually to the shift in behavioural modes. Swarms then start to migrate to find new places to feed.

Preventive lapses

Control responses revolve around pesticide-based strategies. However, these have been shown to be most effective -- and most cost-effective -- as part of a preventive strategy.

Prevention is critical to effective locust management

The principle of prevention is simple: find the locusts when they start to form into small groups or change behaviour and kill the problem before it becomes unmanageable.

Preventive strategies became increasingly effective from the 1960s onwards, with the advent of large-scale air-sprayers and more efficient pesticides. This led to a massive reduction in the recurrence rate of locust crises, the length of plagues and the extent of impacted areas.

Preventive management is based on anticipation, international cooperation and coordination. Locusts move and reproduce fast, and quick and precise reactions are therefore necessary, with forecasting and information transfer a critical component of a successful strategy. The Western Commission for Desert Locust Control (CLCPRO) (covering West and North Africa) is perhaps the best example of such an approach.

Unfortunately, governments have short memories and preventive management can eventually become so successful that memories of previous plagues begin to fade. Often, countries that have not experienced swarms for many years decrease their attention to preventive management strategies. Then, when outbreaks recur, those countries are not ready. Indeed, all modern-era plagues have started in countries where prevention was not efficiently pursued.

The last desert locust plague was in 2003-05 and started in West Africa. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) initially called for 9 million dollars to contain the situation. However, funding was slow to materialise and a response slow to mobilise. Ultimately, management of the crisis cost over 400 million dollars, while crop damage was estimated at some 2.5 billion dollars.

A new plague

The current plague originated in the 'Empty Quarter' of the Arabian Peninsula around a year ago. Good climatic conditions and lack of early control allowed locust populations to multiply and expand, cycling through around eight generations of multiplications with successive good rains in different parts of the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa.

As the swarms multiplied, they also spread to Iran, Pakistan and India. However, the control responses in these countries were efficient. In contrast, in conflict-affected countries such as Yemen and Somalia, or in countries where swarms had not been seen for a long time, such as Ethiopia or Djibouti, preventive management was minimal, and the swarms quickly began to spread.

The plague has now spread to countries that have not been hit since the generalised plague of 1948-63 (Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania). This is because of three intertwined factors:

- abnormally heavy rains in the Arabian Peninsula since 2018 and the Horn of Africa since mid-2019;

- non-existent or inefficient preventive management systems in these areas; and

- a slow international response to the developing situation.

Outlook

In late January, FAO launched an appeal for 76 million dollars in funding for rapid response and anticipatory action across the wider Horn of Africa. However, to date only 21.6 million dollars has been mobilised, leaving a gap of more than 50 million dollars. Quick funding will be key to managing the crisis as it currently stands.

A rapid response is key to managing the current crisis

Most of the swarms infesting East Africa are currently breeding and laying eggs. This represents an important window for intervention, to prevent new generations of locusts maturing. Under present conditions, however, it is likely that most of the current swarms will manage to reproduce (see EAST AFRICA: Locust infestation may worsen - February 19, 2020).

Huge amounts of pesticides will be needed to tackle a plague of this size, and FAO is already buying or triangulating the necessary materials. However, complex logistics mean at least another month will be needed before efficient treatments can start, and more funding will be required if treatments are to be sustained.

Similarly, rebuilding the necessary capacities in the affected countries will take time. Plant-protection specialists will be required, with training on the technical specificities of deploying ultra-low volume sprayers, barrier treatments and biopesticides.

Even with an efficient response, the anticipated new swarms are likely to match the levels that caused such alarm in January. If control measures are inefficient, the levels could double -- or worse (see AFRICA: Locusts threaten East Africa food security - February 6, 2020).

Similar outcomes have been seen in past plagues. For example, North Africa, despite having strong capacities to deploy aerial treatments, could not kill all the swarms that arrived from the Sahel in the winter of 2003-04. This led to further multiplication and, when the swarms returned to the Sahel in the summer of 2004, the impact was catastrophic and cost 40 times more to control than the initial appeal for funds.

This is a clear lesson from past plagues: the slower the response, the higher the costs.

For now, the affected countries should expect a long fight before the situation can be brought back under control -- at least a year, more likely two. Meanwhile, countries in West and North Africa that are currently not under threat may soon face a risk, as previous patterns of migration suggest swarms could begin to move west from around May or June.