US federalism complicates cooperation on COVID-19

The US response to COVID-19 is hampered by disagreements over where power and authority rest

The US federal system purposely disperses government powers widely. The response to COVID-19 has therefore seen a patchwork of national and local actions, which in some cases conflict. However, the same system allows local leaders to take critical action unilaterally, and many are.

What next

State and local action will be key to controlling COVID-19. State governments will in some cases introduce complementary policies, but their freedom of action, alongside differing local cultures and capacities, mean cooperation and harmonisation are not guaranteed. The federal government cannot increase its power to control the situation without bipartisan and state agreement, an unlikely outcome unless the president unilaterally invoked national emergency authority, such as the Defense Production Act.

Subsidiary Impacts

- States will seek further COVID-19 fiscal support; Congress could pass a fourth aid bill this week.

- Differing state fiscal and medical capacities will affect the success of their COVID-19 responses.

- Pressure will mount on Trump to make full use of presidential powers against COVID-19.

- Currently there is no pressure to reform federal or state emergency management systems, but this could come.

- Court cases will be initiated, seeking greater clarity on what public health-related powers state and federal officials hold.

Analysis

President Donald Trump, who seeks re-election in November, has been criticised by some governors for what they see as lack of leadership in mitigating COVID-19. Trump's critics have argued that the federal government has failed to make the required amount of test kits and personal protective equipment available. In response, Trump said yesterday that not all governors are aware of the various efforts underway, and that others' criticisms were politically motivated.

The president has rejected calls for a nationally coordinated response, arguing that such decisions as whether to issue stay-at-home edicts should reside with the governors. Trump has, however, used the Defense Production Act to order US industries to make more ventilators and testing kits.

On March 13, he also declared a national emergency, which allowed 50 billion dollars to be released to help fight COVID-19 in various ways. Vice President Mike Pence has been placed in charge of the task force overseeing the US response to COVID-19.

On April 16, the White House released suggested guidelines that state and municipal authorities could follow in relaxing social distancing and economic closures. However, the administration was clear that governors and local leaders would decide whether to follow the suggested three-phase approach, and to what timescale (see UNITED STATES: Trump plan focuses on exit strategy - April 17, 2020).

Trump has suggested May 1 to 'reopen' to the economy, but this month he has appeared to support protesters calling for speedier relaxation of social distancing and economic closures (see UNITED STATES: Virus demonstrations may grow soon - April 20, 2020).

Constitutional prerogatives

Without an overarching nationally directed strategy, it is falling upon state and local officials to lead. This month, for example, governors of states on the East and West coasts, and in the Midwest, have formed three regional task forces to coordinate their COVID-19 policies and economic reopening plans (see UNITED STATES: States prepare for economy restart - April 14, 2020).

However, states have disparate capacities, such as in healthcare and policing, while others are not coordinating. Therefore, there are limits to the likely success of the cooperation pacts and policy harmonisation.

The federal system is the root of this diverse response. The Founding Fathers rejected a strong, centralised government for a largely decentralised distribution of authority. The US Constitution limits federal power primarily to foreign policy, national security and regulating interstate and foreign commerce. All remaining government powers are reserved to the states.

The constitution reserves significant governing powers to the states

Over time, the power to regulate interstate commerce has been interpreted broadly in various court decisions, so the national government's power has grown substantially. Nonetheless, considerable independent power remains in state and local officials' hands. States control civil law, most criminal law, public education, public health, business and professional licencing, among other duties.

Trump's reaction

A federal system allows policy to reflect common social and communal values of people where they happen to live. It also recognises that states may best be able to solve problems in different ways. However, it is during crises and emergencies, as now, that federalism's shortcomings are clear.

Federal systems can make for responsive government, but not always in crises

Trump effectively is resorting to traditional federalism practices when he declares that it is not the national government's responsibility directly to acquire and distribute critical medical supplies nationally, for example, and that states should themselves bid for the products.

The result is that states are now in a bidding war for critical supplies including ventilators, as additional supplies become available. This is driving up prices and items are being distributed in part based on ability to pay, not critical need, forcing difficult medical decisions later on.

Critics are calling on Trump fully to employ the federal government's powers, particularly through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), to nationalise the country's response to COVID-19. They advocate that Trump issue a national stay-at-home edict (a power he may lack over the states), impose controls on prices of protective equipment and ventilators, to prevent price gouging, and distribute supplies based on need.

Governors' reactions

Currently the states most affected by COVID-19 cases and deaths are Massachusetts, New Jersey and New York, followed by Michigan, Pennsylvania, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Texas and California.

The national average of tests with results per 1,000 people of population is 11.9%, healthcare non-profit the Kaiser Family Foundation records, led by Rhode Island at 32.8%, with Kansas at the other end on 6.2%.

COVID-19 testing is taking time to come online

All states except six have issued stay-at-home edicts, and three have partial orders. All states have also ordered non-essential businesses shut, except nine that have partial closures. However, seven states have ordered no business closures.

Most states have put limits on bars and restaurants' operations; one state has not and three have partial limitations. All states except two, which have effective total closures, have ordered schools closed. Additionally, all states except three have limited public gatherings, either entirely or of over 50 or of over ten people.

Coordination -- and friction

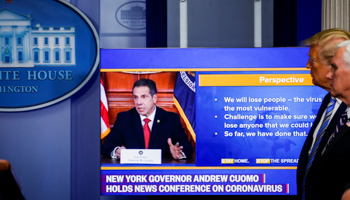

Governors Andrew Cuomo (Democrat, New York), Mike DeWine (Republican, Ohio) and Larry Hogan (Maryland, Republican) are among those local leaders being publicly heralded for their crisis leadership by imposing strict social distancing and other restrictions.

However, there have been frictions between government levels. In Mississippi, for instance, when local governments issued public gatherings bans, Governor Tate Reeves (Republican) effectively over-rode their actions by declaring most businesses essential.

There are examples of effective regional coordination, notwithstanding the three pacts. For instance, at a time when Trump had initially questioned the wisdom of social distancing, the governors of Maryland and Virginia with Washington DC's mayor committed to work together to ensure social distancing in their jurisdictions.

They also united to issue stay-at-home edicts. It was the three jurisdictional leaders, not the federal government, who jointly enacted measures to protect upwards of 360,000 federal employees, many of which are at work in areas critical to resolving the COVID-19 crisis.

Despite some effective coordination, jurisdictional differences will hamper fighting COVID-19

Even so, there are still policy differences. Maryland's stay-at-home order comes with criminal penalties for non-compliance and persons holding large gatherings at home have been prosecuted. Yet Virginia's order has no penal action threat and could be ignored.