Securitised Middle East COVID-19 responses raise risks

Lebanese, Iraqi and Emirati security forces face different challenges in supporting public health measures

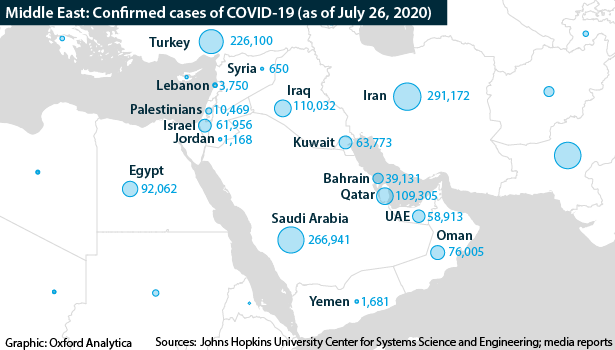

Across the region, security forces have been mobilised to implement and enforce their COVID-19 responses -- but in varying contexts. The pandemic has compounded existing economic and political crises in Beirut and Baghdad, with the securitisation of the response straining military and state legitimacy. Conversely, despite some privacy concerns, stringent measures in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) were broadly welcomed in a context of strong state control and ample healthcare provision.

What next

Middle Eastern national defence priorities will likely turn inward in the medium term. New COVID-19 surges in Iraq and Lebanon increase the likelihood of protesters clashing with the security forces enforcing renewed lockdown rules, with many people -- already suffering economically from the pandemic -- ignoring social-distancing measures. In the UAE, weapons purchases and regional military engagements could come under pressure.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Years of under-investment in public health in some countries mean medical shortages may drive new anti-government demonstrations.

- Where security forces are mistrusted, their involvement in the pandemic response could undermine health outcomes.

- COVID-19 might draw global attention away from the Middle East, changing local security and defence configurations.

Analysis

Many Middle Eastern countries have securitised their responses to the pandemic, depicting it as a conflict and employing the military or police to implement and enforce their policies. The approach has consequences for public trust and political priorities, and lays bare the linkages between security, healthcare and the economy.

However, there are also significant contrasts, partly related to existing levels of political stability. For instance, in divided Lebanon and Iraq, COVID-19 arrived amid economic and political crises, following six months of public protests against government shortcomings.

This is wholly different to the context in Gulf countries, with much higher national income, lower poverty rates, a strong state and security apparatus and communal cohesion. The UAE is a lead performer in these respects, and on the security side is also notable for its external military engagements.

Lebanon

Beirut's introduction of a strict lockdown in mid-March included a "general mobilisation" directive to the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF), which swiftly reassigned some 40,000 troops (half of its strength) to deal with the pandemic. The military created a COVID-19 crisis response committee spanning its branches, enforced the curfew, maintained public order and aimed to source medical supplies for its own use.

In the longer term, this level of diversion of resources would make it difficult for the LAF to maintain its traditional national defence priorities, such as maintaining stability on the border with Syria and developing specialised units to counter chemical and other threats.

Legitimacy risks

There are also wider legitimacy risks.

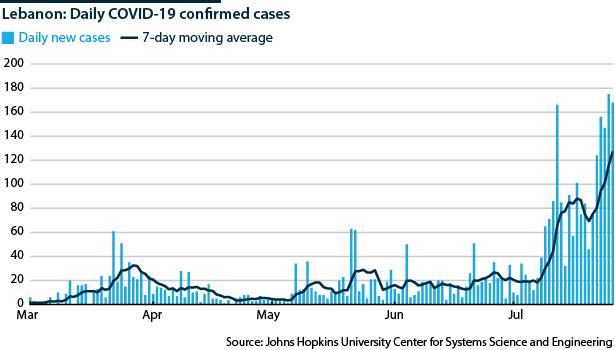

Short of funds, Beirut has failed to strengthen the health system, which has been heavily hit by the worsening economic crisis (see LEBANON: Beirut faces a huge aid and reform challenge - May 15, 2020). Cases are once again rising after the lockdown lifting on June 8, with daily cases reaching new highs in July.

The Lebanese health minister today recommended a fresh two-week lockdown. Even though absolute numbers remain low, hospitals lack funds and supplies to meet the challenge.

Demonstrations will be a mounting challenge

Instead, the government's approach has focused on public order, with the lockdown providing a reason to clear street protest camps established in October 2019 (see LEBANON: COVID-19 may give premier a short-term boost - April 17, 2020). However, protests have since resumed, driven by rising poverty and hunger, in an economy where much employment is informal, and many depend on the suffering tourism and hospitality sectors.

The military and riot police responded to fresh protests in Tripoli and Beirut with tear gas, flash bombs and live rounds, warning against further demonstrations (see LEBANON: Protest leaders will struggle for control - June 29, 2020). The internal security forces are also cracking down on increasing breaches of social-distancing measures and quarantines imposed after the resumption of flights on July 1, posting pictures of police patrolling beaches on Twitter on July 25.

Enforcing a nationwide public-order mission in this crisis period could make the military and security forces a target of public dissent, undermining troops' morale as well as the LAF's traditional role as a rare focus of national legitimacy (see LEBANON: Army faces rising pressure over Hezbollah - August 13, 2018).

Decentralisation

This is also imperilled by a wider context of fragmentation.

The government's national welfare system is inadequate to meet rising demand. External assistance would depend on negotiations with the IMF, which are now faltering as political leaders resist proposed reforms that would imperil their power, instead reverting to a logic of sectarian clientelism.

With the government's economic resources declining, its national authority may erode in favour of municipal political actors. These provide support for the rising numbers of poor households, including food assistance, medical treatment and jobs, as well as short-term benefits during elections such as cash or food handouts.

This political fragmentation would also be reflected in security terms, with local-level, informal and sectarian security forces -- including private security companies, citizen groups and political party militia wings -- increasingly in competition with the LAF.

Most prominent are the armed forces of Shia political-military movement Hezbollah, which has mobilised some 25,000 medical workers and activists to fight the pandemic. This has been presented as a non-military action, demonstrating the party's welfare provision, resilience and resources, while distancing it from the government's economic and political woes.

Iraq

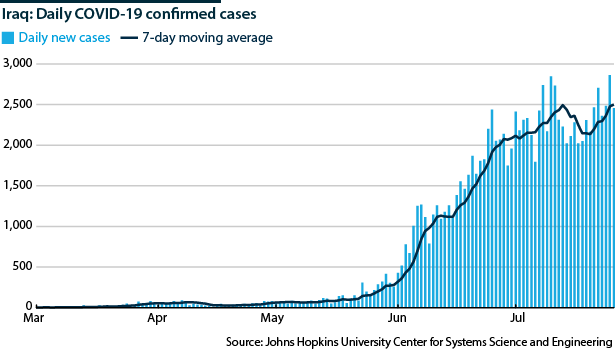

Iraq's fairly strict lockdown was initially successful in containing COVID-19, but recorded cases have mounted sharply since it was lifted on June 14, exceeding 100,000 on July 23. Despite this, Baghdad has confirmed plans to lift the 7pm-6am curfew in August.

The response has relied on the federal police collaborating with the Ministry of Health to impose curfews. The army has also been involved, for instance in staffing checkpoints to enforce restrictions on movement.

However, the response has been mixed, reflecting low public trust in public institutions because of corruption and militarisation, which has in numerous cases meant families refused to turn over sick relatives to medical teams.

Political economy pressures

The issue is that the same security establishment now enforcing the COVID-19 response was since late 2019 implicated in violent repression of mass protests against the political system. Exact attribution is deeply contested, with a murky role played by sectarian militias and local security forces, as well as 'unidentified' gunmen.

Consequently, when COVID-19 hit, Baghdad was also in a deep political crisis, with parties having failed to agree on a new prime minister or government since November. This has been eased since the May appointment of Mustafa al-Kadhimi, a former intelligence chief, as premier. He immediately released jailed protesters, promising justice and compensation to relatives of people killed in the demonstrations.

However, new protests are now breaking out over electricity shortages during a summer heat wave. Yesterday Baghdad police using tear gas to disperse crowds killed two people, undermining Kadhimi's reform credentials and raising risks of more widespread protest. On the economic side, protests, the pandemic and lower oil prices have hit state revenues hard, putting state finances under deep strain at a time of rising need (see IRAQ: New premier will take drastic economic steps - May 11, 2020).

In particular, the chronically underfunded healthcare sector is warning of an imminent crisis as cases rise. International aid is likely to come through, given Western countries' support for the appointment of Kadhimi and his finance minister, Ali Allawi, an experienced and respected technocrat, but will not fix Iraq's fundamental structural economic problems.

2.5%

Proportion of the budget going to the health ministry

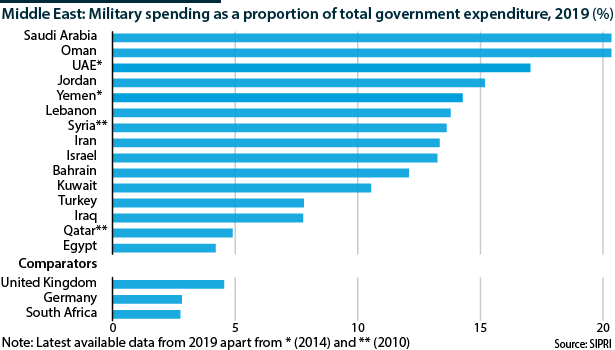

Baghdad has long sought short-term stability through investment in security forces and political allies at the expense of institutions supporting health, education and prosperity. The health ministry receives just 2.5% of the budget (see IRAQ: Divided Baghdad faces a massive economic hit - April 23, 2020).

Though COVID-19 could increase pressure for a changed approach, this will be difficult to implement, given the swelling youth population, lack of resources, weak infrastructure and sectarian elites' grip on power.

Security priorities

More directly, a hybridised sector risks complicating the COVID-19 response.

There are four major defence forces of differing sizes and capabilities: the Counter Terrorism Service, the national army, the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF -- mostly Shia militias, many linked to Iran) and the Kurdish 'peshmerga' militias. Separately, Iraq has a federal police and other local forces tasked with maintaining law and order.

The new government aims to restrain militia activity (see IRAQ: Premier and militias in slow-burn confrontation - July 15, 2020). It has also promised accountability for earlier attacks on protesters -- although this may be limited to fact-finding, as Kadhimi cannot afford to alienate significant chunks of the security establishment. He is therefore striking a delicate balance in his efforts to rein in the PMF.

This is complicated by the fact that COVID-19 has encouraged the United States, with other members of its coalition fighting Islamic State (IS), to draw down troop numbers and hand over some bases. Iran is keen to encourage this trend.

However, the pandemic has also opened opportunities for non-state actors, including IS, to present alternatives to the state and assert their control. IS increased its attacks in northern Iraq during the early stages, and the military has stepped up containment efforts.

United Arab Emirates

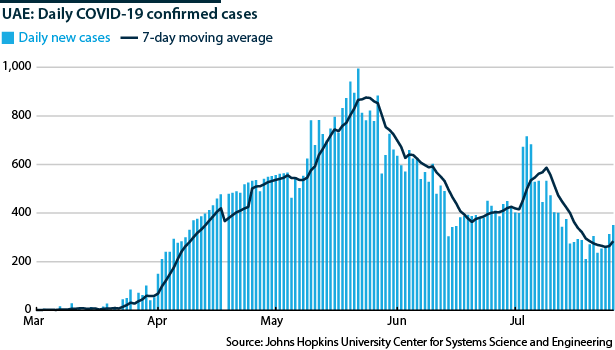

The situation is far different in Gulf countries such as the UAE, where highly functional security apparatuses under strong central control have been enlisted to help implement a pandemic response making use of rigorous testing and contact tracing (see GULF STATES: COVID-19 could deepen social cleavages - April 8, 2020). Cases numbers have largely been brought under control, despite a small second peak in early July, after restrictions eased.

In the UAE this applies at the level of the individual emirates, which have seen some differences of approach. The country has a federal army and the Ministry of Interior oversees police and security forces, but local law enforcement is devolved.

Security and surveillance

Dubai's original strict lockdown in April required people to obtain police permission to leave the house through an online application system, even in cases of emergency. They had to state their reason for going outside and input details including nationality, job, phone number, ID number and vehicle licence plate number (if driving). Going outside for exercise or dog walking was forbidden, with permits only allowing 'essential' trips for food or healthcare.

Other emirates did not require police permits, but the security forces have still been closely involved in controlling movement -- for example, until mid-June, Abu Dhabi restricted passage between districts and banned travel from the other emirates.

The pandemic response has made use of the UAE's advanced digital infrastructure that accelerates the policing of information. A sophisticated surveillance programme implemented by Dubai Police for criminal investigations, Oyoon, has also been adapted in an effort to use facial recognition software and thermal imaging technology to detect COVID-19.

USD5,500

Maximum fine for COVID-19 'fake news'

Like other countries, it is encouraging residents to download contact-tracing apps, raising potential privacy concerns. The pandemic has also given rise to an increase in the spread of false information and associated crackdown by law enforcement. The UAE has introduced fines of up to 20,000 dirhams (USD5,500) for people "publishing or re-publishing false and misleading health information" (see MIDDLE EAST: Rumours may dent virus resilience - July 14, 2020).

This security-led approach, enforcing close formal and informal social control, has nevertheless generated no appreciable domestic pushback. In part, this is because of a political environment that allows little room for criticism of the security services. However, it also reflects the adequacy of the COVID-19 response on the civilian side.

Economic trade-offs

The UAE has the second-largest economy in the Middle East, with GDP of USD414bn, almost double that of Iraq and eight times the size of Lebanon's. It was therefore able to step up its healthcare outlay, engaging private healthcare providers to make staff and hospital beds available for COVID-19 patients.

Still, in the longer term there may be trade-offs with the country's relatively high level of defence spending. Some resources have already been diverted: for instance, defence company Strata was asked to start manufacturing N95 masks.

The pandemic could potentially widen definitions of 'national security' to include issues such as public health, overseas aid and food security, increasing their priority. The UAE imports as much as 90% of its food, but the recent disruption to supply chains has revived demands to increase local production (see GULF STATES: Food security strategy will be bilateral - June 15, 2020).

Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, as deputy supreme commander of the UAE armed forces, has made investment in defence equipment and training a central priority. However, the COVID-19-related slump in the oil market will likely require cuts (see BAHRAIN/OMAN: Muscat and Manama face most Gulf risk - May 6, 2020). The UAE will seek to ringfence current military spending, which includes salaries and benefits for personnel that are part of the fundamental social contract.

Arms purchases might come under pressure, even though they are inseparable from the country's foreign relations and outreach. The UAE's emphasis on developing an indigenous arms industry as a form of economic diversification may also slow.

This could combine with the changing geopolitical environment to reorder some of the UAE's foreign military priorities. Its role in Libya has received increased negative international attention, as UN calls for a general ceasefire in the country to help manage COVID-19 fell on deaf ears.

With the US regional role on a trend of gradual diminution, there are also signs that the UAE might seek to de-escalate risky confrontation with Iran and its allies such as Syria. Abu Dhabi has sent Tehran COVID-19 medical supplies, marking a significant shift in bilateral relations.