Lifting COVID-19 measures may hit resilient eastern EU

As income support fades out, health uncertainties, weak global demand and disrupted trade may hamper an economic rebound

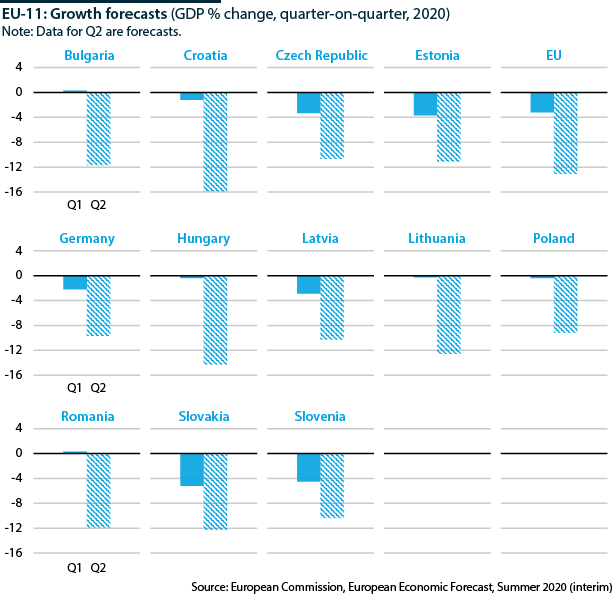

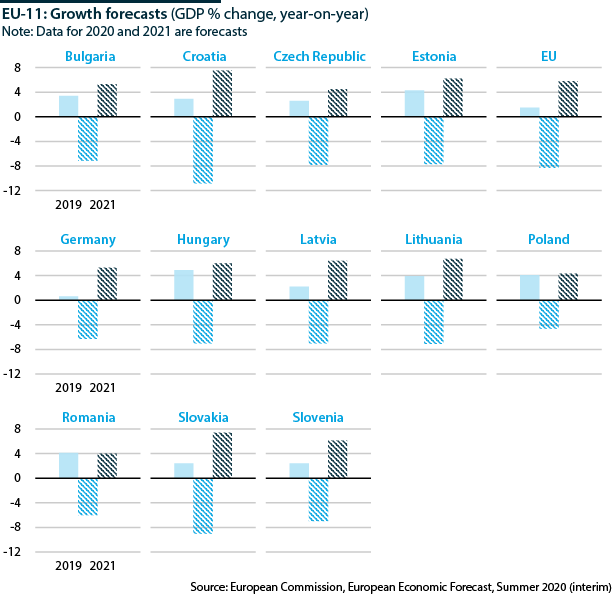

The European Commission published its summer forecast on July 7. Available second-quarter data indicate a shallower recession in most of the eleven eastern EU member states (EU-11) than the rest of the EU in January-June. This may be due to a strong start in January-February, followed by strict but shorter lockdowns and macroeconomic measures introduced to smooth the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact. However, the number of cases is still a concern.

What next

The task of balancing public health and economic concerns will be complex. Capacity to manage the pandemic has improved and the current shallow wave of contagion is mostly under control. However, relative stability may yet be overturned as removing movement restrictions and reopening economic and social activities lead to an accelerating rate of transmission. Important economic partners globally will be heavily affected by the pandemic.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Projections for economic recovery in the second part of the year will be subject to downside risks.

- European solidarity will likely continue to be tested by political controversy over the rule of law.

- A European-wide vision for green, digital transformation and resilience may emerge.

Analysis

The Commission's Summer 2020 Economic Forecast, issued on July 7, indicates steep declines in economic activity for March and April. With the subsequent easing of lockdown measures came a gradual turnaround, to be seen in some retail data, patterns of electricity consumption, Google community mobility reports and indicators of pollution.

Q2 contractions in most of EU-11 were below EU average

There is some divergence between countries as regards the economic impact of COVID-19. On July 31, Eurostat preliminary flash estimates including ten EU economies put the worst affected in April-June as Spain (18.5% contraction quarter-on-quarter). France (13.8%) and Italy (12.4%) also contracted. The deceleration in Germany (10.1%) was below the EU average (11.9%), along with the Czech Republic (8.4%), Latvia (7.5%) and Lithuania (5.1%). Recovery seems likely to prove prolonged.

Greater EU-11 resilience

While full analysis of the factors accounting for this variance awaits more real economy data, it appears likely that the pandemic was more severe and and longer in some sectors than others, with knock-on effects on national economies according to their structure. This is clearly the case with Croatia and Slovakia, whose large tourism and vehicle-manufacturing sectors respectively were badly hit by lockdown, but are expected to rebound quickly once activity resumes.

In general, the EU-11 still have larger rural populations, which are more self-reliant thanks to easy access to food and less susceptible to pandemic transmission because of their dispersal.

They also made a significant start on developing their IT sectors before the pandemic hit, which in some cases helped accelerate the development of online shopping and the digital delivery of other services during lockdown.

Equally, the relatively early relaxation of lockdown and the powerful stimulus spending in Germany, their main trading partner in Europe, may have helped slow down economic decline.

Risks remain significant

All EU-11 introduced strict lockdowns and allocated significant funds to support incomes and to bolster the capacity of the public health system (see EU: Anti-virus policies may hurt democracy in East - March 30, 2020). According to the stringency index in the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, which takes account of all of these measures, by end-March, the level of stringency stood at values as high as 96 out of 100 in Croatia (where the level of income support was less than 50%). Romania, Poland and Czechia had values in the 80s and Slovakia, Hungary and Germany in the 70s.

By end-June and into late July, the stringency index eased significantly and quite steeply in Croatia (24), with most countries hovering around 40. More conservatively, Hungary maintained a stringency level of 52.

While the easing of restrictions is likely to help the resumption of more economic and social activity, the number of COVID-19 cases is also rising. It is beginning to cause alarm in Romania (see ROMANIA: Policy aims to surmount virus’s second wave - May 7, 2020), where there have been more than 1,000 new cases daily since mid-July. Poland is also witnessing a surge, which is being attributed to official messaging suggesting the worst is over.

Countries across the region are constantly reviewing social mobility and quarantine policies: as local conditions vary the rules of social distancing, they become difficult to enforce, while slowing down economic participation. There is also more opportunity for confusion or deliberate non-compliance from exhausted or anxious members of the public.

Governments are balancing between restriction and relaxation

European solidarity and recovery

The success of the EU's leaders in agreeing not only the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) for 2021-27, but also the New Generation EU (NGEU) programme designed in response to the pandemic, came as a great relief (see EU: Recovery deal offers hope for stability - July 23, 2020).

The EU-11 have received important allocations from the NGEU, including the Recovery and Resilience Facility and the Just Transition Fund. Proposals for disbursement procedures at the EU level are to be formulated by October, but actual implementation is likely to be deferred to the beginning of 2021.

Political complications could also arise as the European Parliament seeks to play a greater role and EU institutions attempt to link spending to rule-of-law conditions, which Poland and Hungary are resisting in particular.

Moreover, EU-11 ability to absorb EU funds has been uneven historically. For the current MFF, a high performer in terms of absorption, such as Hungary, has planned the use of its allocation fully, but has spent only 69% so far. At the opposite end, Bulgaria has planned 79% and spent only 40%, with only slightly better figures for the Czech Republic and Poland.

European industrial renaissance?

The NGEU has been adopted with the clearly expressed intent of supporting the European Green Deal, the digital revolution and resilience. The challenges of managing the pandemic have focused minds on the wisdom of globalisation with its long but potentially vulnerable supply chains (see EU: Virus strengthens drive for economic sovereignty - June 10, 2020). According to a Polish Economic Institute report , import substitution for components made in China with local production could lead to significant increases in annual value-added generation in the EU-11, especially in Poland.

EU-11 could benefit if shorter supply chains cut Chinese imports

The EU-11 could become even more attractive for business as a consequence. It already has a good industrial base, with a highly qualified and competitive labour force. It has proven ability to integrate in global value chains that support West European firms and multinationals.

The focus on infrastructure investment through the NGEU will help the region upgrade transport and internet links, supporting its ambition to become a logistics hub.

Strong IT sectors could provide a much-needed edge and opportunity to move up global value chains. A recent Eurostat study estimates that the ICT sector, including services and manufacturing, represented 3.6% of EU GDP in 2017.

While Ireland is a clear leader, with the sector contributing 9.3% of value-added, Hungary and Bulgaria where the ICT sector represents around 5% of value-added have also performed well. Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Croatia were at or above EU levels in terms of ICT sector share in value-added generated by the non-financial business economy.