East Africa may face prolonged pandemic

As vaccination campaigns begin, optimism is tempered by uncertainties over implementation

Kenya on March 2 announced it had received 1 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines from the COVAX facility, making it the first East African country to secure vaccine supplies. Other regional countries are now also receiving COVAX shipments, but all will face enormous challenges in bringing the pandemic under control.

What next

Alongside the COVAX facility, the African Union (AU)’s proactive efforts to finance and secure vaccine supplies means regional vaccination campaigns can commence imminently. However, uncertainties over supply flows, logistical challenges and political constraints suggest it may be years before the pandemic is brought under control.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Regional countries may receive some assistance from donors engaging in ‘vaccine diplomacy’.

- East African nations weathered the economic downturn better than most in 2020, but 2021 may prove difficult as fiscal pressures mount.

- Delays in bringing the pandemic under control would have a serious negative impact on regional economies.

Analysis

When COVID-19 first arrived in East Africa, many feared a major health crisis across the region (see AFRICA: UN warns COVID-19 deaths could be in millions - April 17, 2020).

In particular, limitations in national health capacities, societal challenges in implementing preventive measures and the high prevalence of potential co-morbidities raised fears that the virus could spread rapidly and result in an elevated death rate.

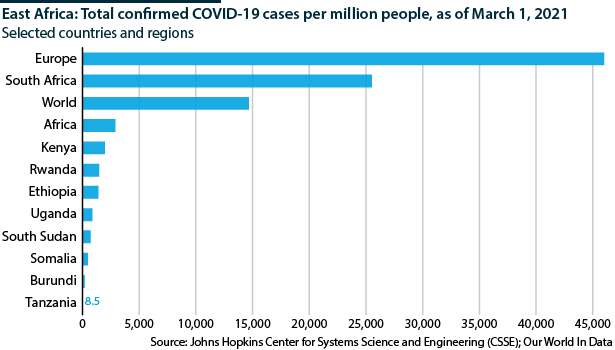

However, so far at least, this has not been the case; official figures of confirmed cases across the region -- whether in absolute or per capita terms -- have been far below the main hotspots even within Africa, let alone the rest of the world.

Hidden pandemic?

Explanations for the region's low exposure remain debated, but include factors such as proactive preventive measures, younger and more dispersed populations, climatic differences, genetic differences and stronger immune responses (see AFRICA: COVID-19 situation remains precarious - May 22, 2020).

However, it is also clear that part of the explanation is that official numbers are gross underestimates.

The regional pandemic is likely worse than official figures suggest

Even in countries such as Kenya and Uganda where testing regimes have been fairly robust, mass screening operations have returned average rates of per capita infection that are vastly above those suggested by official case numbers.

A sense that the pandemic may be more widespread than acknowledged has also been reinforced by several prominent cases of severe sickness or death among various high-ranking officials.

In the most notable recent example, the vice-president of Tanzania's Zanzibar region, Seif Sharif Hamad, died on February 17 after acknowledging he had COVID-19. Hamad's case was particularly pertinent given that Tanzania has officially claimed to be COVID-19-free since May 2020; as such, it has offered no updates to official case numbers since then.

Hamad's death has forced a very limited shift in official discourse, with government officials now acknowledging the dangers of unspecified respiratory illnesses, but there is still no sign of an official government policy to contain the pandemic or even gauge its scale (see TANZANIA: COVID-19 disinformation imperils credibility - May 19, 2020).

Similarly, in Burundi, authorities dismissed the risks posed by COVID-19 until President Evariste Ndayishimiye took power in June -- after outgoing President Pierre Nkurunziza died unexpectedly of what many believe was complications related to COVID-19 (see BURUNDI: New president faces old challenges - June 19, 2020).

Shortly thereafter, Ndayishimiye declared COVID-19 Burundi's "worst enemy" and promised mass testing and preventive measures, but these were undertaken with little enthusiasm and, in September, Health Minister Thaddee Ndikumana abruptly declared the epidemic contained.

Politicised pandemic

Tanzania and Burundi represent extreme examples, but elsewhere in the region attempts to contain the pandemic are also hampered by political factors.

For example, the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) has warned that the conflict in Ethiopia's Tigray region and broader domestic instability is likely to extend significantly the time required to bring the pandemic under control.

Meanwhile, in Uganda, the COVID-19 response has been politicised in other ways. After a thoroughgoing lockdown, authorities promised to keep campaigns for the 2021 elections off the streets. However, the ruling party proceeded to hold mass rallies with little social distancing, while opposition leaders and supporters faced a violent campaign of suppression for allegedly violating COVID-19 restrictions (see UGANDA: Campaign clashes presage post-election unrest - December 4, 2020).

More recently, in Somalia, amid an increasingly tense electoral crisis, the government announced new restrictions on public gatherings just days ahead of planned opposition protests, which it then cracked down upon. It is now considering a wider lockdown, even as the opposition considers further protests (see SOMALIA: Election clashes may presage further violence - February 19, 2021).

All these episodes have served to weaken already fragile public trust in government -- and in COVID-19 containment measures.

Vaccine preparedness

Vaccine roll-outs offer an opportunity to reset the paradigm and start to build a positive path out of the pandemic. On this front, there have been several positive developments.

Notably, the AU has been proactive in vaccine procurement: its new African Vaccine Acquisition Task Team has already secured 670 million doses, mainly of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine. Talks to acquire 300 million Sputnik V doses are reportedly well advanced. Alongside a promised 600 million COVAX doses, this in theory brings the continent close to its target of 1.5 billion doses to vaccinate 60% of the population.

The African Export-Import Bank is supporting the AU initiative through USD2bn in advance procurement commitment guarantees for manufacturers, while offering flexible financing for African nations seeking loans to cover procurement costs.

The Africa Medical Supplies Platform has been established as a clearing house for vaccine orders and related medical supplies. Ethiopian Airlines has announced a partnership with the logistics arm of China's Alibaba Group to set up cold-chain storage and air-freight infrastructure to deliver vaccines across the continent.

Roll-out challenges

Nevertheless, enormous challenges remain. The AU and COVAX supply chains the region is so dependent upon face deep uncertainties over how quickly supplies will materialise.

It is unclear when vaccine supplies will become available

For example, Ethiopia says it has ordered 42 million vaccine doses, Kenya 24 million and Uganda 18 million. However, under COVAX's initial allocation until June, Ethiopia will receive just 7.6 million, Kenya 3.6 million and Uganda 3 million. Similarly, the AU says only 50 million doses will be available for the entire continent before June. There is no clarity over when further supplies will become available.

Few regional countries have released detailed vaccination plans, while Tanzania and Burundi say they do not intend to seek vaccines at all.

Of those with clear targets, Rwanda is the most ambitious, aiming to vaccinate 60% of the population (8 million people) by end-2022 and 30% by end-2021.

Kenya's more detailed plan envisages vaccinating 30% of the population (16 million people) by June 2023; authorities hope to accelerate this timeline, but this depends on vaccines arriving smoothly and further doses being secured through bilateral deals (see KENYA: Vaccine delivery starts nation on long path - March 3, 2021).

Securing more vaccines may prove challenging given extensive geopolitical competition over limited supplies. Moreover, given shortages of cold-storage capacities outside major cities, most regional nations must concentrate on acquiring vaccines that do not require ultra-cold storage.

Cost is a major issue too: even with financial support mechanisms, procurement costs will place heavy strains on national budgets already under pressure from the economic downturn.

All this suggests it will be some time before vaccines make a noticeable impact on the regional epidemiological situation, and years before the pandemic is brought fully under control.

This timeline could even be extended if new variants prove resistant to current vaccines or if booster shots are required. Indeed, the Africa CDC warns that, unless vaccination plans accelerate, COVID-19 may simply become an endemic problem across Africa.