Lula’s ‘return’ will upend Brazilian politics

The former president's possible 2022 candidacy has radically changed the election calculus for other potential hopefuls

Brazilian politics -- especially the jockeying for position ahead of October 2022 presidential elections -- was upended this week when Supreme Court (STF) Justice Edson Fachin annulled the corruption convictions of former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva. This paves the way for the 75-year-old centre-left leader to run against his nemesis, far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, who will seek a second term.

What next

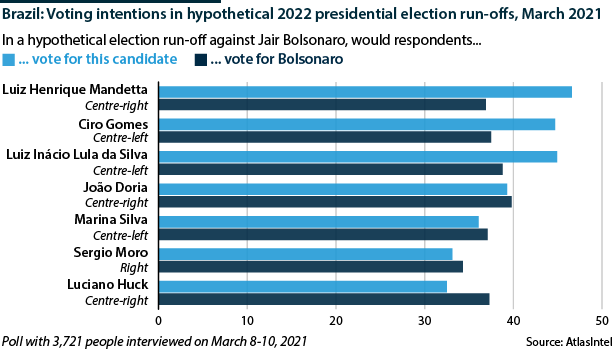

New rulings could still prevent Lula from running, but this seems unlikely. If Lula runs, he could gain the support of much of the spectrum of fragmented left-of-centre groups. Lula has the potential to be a formidable adversary for Bolsonaro, who faces increasingly fierce criticism for his mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic. A Lula candidacy would also intensify pressure on the potentially viable candidates on the centre-right.

Subsidiary Impacts

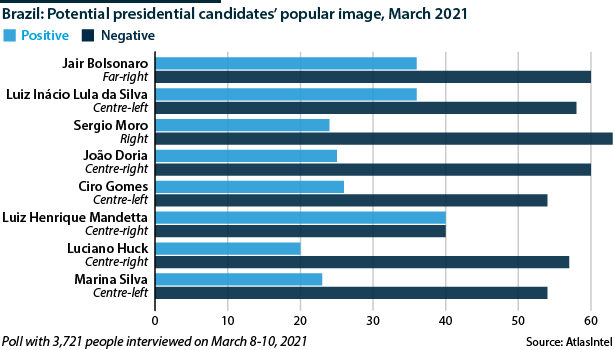

- A Lula candidacy would see a sharply polarised contest between two controversial candidates with high disapproval ratings.

- Bolsonaro’s greatest electoral hope would be an economic rebound ahead of the vote.

- The outlook for future measures to combat corruption looks increasingly dubious.

Analysis

Two cases in which Lula had been convicted, both by lower courts in Parana state and on appeal, are affected by Fachin's ruling:

- In one, Lula is accused of illegally supporting construction company OAS to gain contracts with state-controlled oil company Petrobras in exchange for improvements to a seafront flat in the Guaruja resort town; the property never belonged to Lula but prosecutors claim this is because the deal was made public before it was completed.

- In the other, Lula is also accused of helping OAS and other construction companies obtain contracts with Petrobras, this time in exchange for improvements to a rural property in Atibaia -- again, the property is not in the former president's name, though prosecutors claim he was its actual owner.

Lula's first conviction on first appeal -- in the Guaruja flat case -- removed him from the 2018 presidential race months before the election, when he led in opinion polls. This is due to the "Clean Slate" Act, which bars politicians whose convictions have been upheld on appeal from running. Fachin's decision means Lula is again eligible to run.

Fachin's ruling

Fachin did not issue a judgement on whether Lula is innocent or guilty. Rather, he determined that the Curitiba lower court lacked jurisdiction over these and other cases involving Lula in the Operation Car Wash corruption investigation, and that these must be heard by courts in Brasilia.

This argument is separate from another presented by Lula's defence, which questions the impartiality of former Curitiba Judge Sergio Moro, who led the Car Wash task force in Curitiba for years and sentenced Lula in the Guaruja case before leaving the judiciary to become Bolsonaro's justice minister. This risks raising wider questions over the Car Wash probe, which was recently halted by the government.

Controversial Moro

Moro's decision to join Bolsonaro's cabinet -- which he left acrimoniously last year (see BRAZIL: Bolsonaro fighting for political survival - April 27, 2020) -- was highly controversial, since Bolsonaro's candidacy was boosted by the former judge's Car Wash decisions.

Moreover, in June 2019 leaked Telegram conversations indicated that, as judge, Moro collaborated with the prosecution to convict Lula -- and that the prosecution believed it lacked solid evidence against the former president (see PROSPECTS H2 2019: Brazil - June 26, 2019).

When these chats came to light, Lula was serving his sentence in the Guaruja case. He remained in jail between April 2018 and December 2019, when STF Justice Marco Aurelio Mello ruled that people convicted should remain free until all possible appeals are exhausted.

Lula is likely, but not certain, to run in 2022

Can Lula run?

There is no guarantee that Lula will be able to face Bolsonaro head-to-head next year.

The former president, also previously acquitted of different accusations, still faces court cases outside Parana state that are not affected by Fachin's ruling. However, these are all in their initial stages and are unlikely to have concluded before the 2022 vote.

A separate threat to Lula's potential candidacy is that the Federal Prosecutor's Office has pledged to appeal against Fachin's ruling, requiring a new vote by the STF, though jurists believe this is unlikely to change the decision.

Additionally, there are two situations in which the Curitiba cases would return to square one:

- if the new Brasilia judge -- to be determined in a draw -- decides against using evidence gathered in Curitiba; or

- if the STF accepts the defence's argument that Moro was not neutral in cases involving Lula -- a pending decision which, judging by initial votes, seems likely to favour the former president.

In either case, all evidence would have to be collected from scratch, making an initial ruling -- let alone the conclusion of all possible appeals -- highly unlikely before the elections. Moreover, the statute of limitations in some, though not all, accusations against Lula will lapse by end-2022.

Moving to the centre?

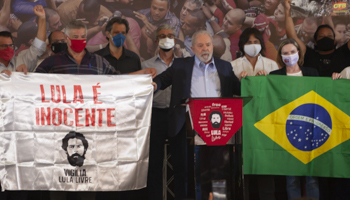

Lula did not waste time in taking back the centre stage following Fachin's ruling. In a speech on March 10, he sought to project a moderate, presidential figure in opposition to Bolsonaro's anti-democratic messaging (see BRAZIL: Democratic debility risks are mounting - June 10, 2019)

Lula will present himself as a moderate social democrat

He also sought to build bridges to financial markets and the business community. Though he criticised privatisations and highlighted his view that the state should play an important role in steering the economy, Lula also indicated he sees a fundamental role for the private sector and reminded businesses of their prosperity during his 2003-10 presidency.

Different, though not all, potential centre-left candidates would likely coalesce around a Lula candidacy already in a first round (see BRAZIL: Centre-left fails to exploit government woes - May 28, 2019).

Right options

The right and centre-right -- except Bolsonaro -- has different potential candidates, including Moro, former Health Minister Luiz Henrique Mandetta, Sao Paulo Governor Joao Doria and popular TV host Luciano Huck.

All would probably have had some chance; and recent trends have been favourable to their ideological camp (see BRAZIL: Local polls boost centre-right hopes for 2022 - December 3, 2020). However, Lula's 'return' creates for the first time a strong centre-left alternative to Bolsonaro which could divert a share of their votes.

These candidates will be more likely to reach a run-off if they are able to form a united front ahead of the first round, avoiding a fragmentation of the conservative vote that does not want Lula's Workers' Party (PT) back in power but also rejects Bolsonaro's extremism (see BRAZIL: Polarisation may give way to fragmentation - January 27, 2020).

Bolsonaro prospects

Lula's 'comeback' gives Bolsonaro the opportunity to polarise the debate with the centre-left, a situation he exploited masterfully in 2018.

Next year, however, he may be unable to repeat the trick. In the last elections, the PT had recently left government after 14 years in power marked initially by prosperity and income distribution, but then by the Car Wash scandals and a profound recession. Now it is Bolsonaro who has to defend a legacy that will be characterised by a gross mismanagement of the pandemic -- in recent days, Brazil has recorded over 2,200 daily deaths -- and its economic fallout (see BRAZIL: Policy inconsistency will damage economy - February 25, 2021).

However, the Lower House yesterday passed an emergency relief bill allowing for the continuation of welfare payments to vulnerable people, which had ended in December. These had bolstered Bolsonaro's popularity last year and helped ensure a milder-than-expected contraction of 4.1% in 2020. This is likely to guarantee monthly payments of BRL250 (USD45) for another four months to low-income sectors battered by recession and COVID-19, which could soften the decline in Bolsonaro's approval seen in recent months.