Pandemic takes tough toll on informal women workers

Informal women workers have been the hardest-hit economic group worldwide

The COVID-19 pandemic has had disproportionately negative effects on women in the informal economy compared to other worker groups. Policy measures taken in response to the economic crisis created by the pandemic have largely been gender-blind, exacerbating the long-standing economic precarity and gender inequality experienced by this group, among whom are many of the world’s poorest women.

What next

Without long-term and explicit commitment to gender-responsive policy, the crisis will limit the expansion of quality employment and social protection to improve female informal workers’ economic security. Female informal workers will be disproportionately concentrated in sectors increasingly deemed ‘essential’ but characterised by hazardous, unprotected and low pay.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Post-pandemic permanent changes in sectors such as retail and hospitality will further narrow employment opportunities for women.

- The push for fiscal consolidation, by governments and multilateral funders, will hit public spending, on which the poorest are most reliant.

- Lack of gender-sensitive policymaking during post-pandemic recovery will widen economic and social gaps for informal women workers.

Analysis

The informal economy has long been associated with economic precarity and gender inequality, which the pandemic has exacerbated.

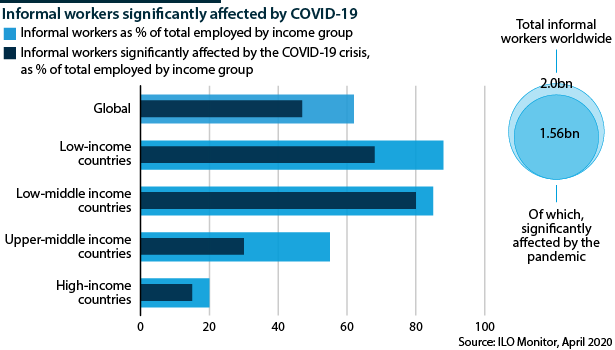

Of the 2 billion informal workers in the world, according to the ILO’s 2018 data (the latest available), over 740 million are women. However, the concentration of women in the informal labour force varies by region: a higher share of women than men were in informal employment in more than 90% of countries in sub-Saharan Africa, 89% of southern Asian countries and almost 75% of Latin American countries.

Moreover, women have been concentrated in informal economy areas with the worst working conditions, for example in domestic work, home-based work and as unpaid workers in family businesses or in agriculture. Research shows that these types of employment are most likely to be associated with poverty, precarious working conditions, and lack of labour and social protection.

Pandemic problems

The pandemic has exacerbated gender gaps in the informal economy

Emerging data signal significant negative effects for female informal workers as the crisis has unfolded.

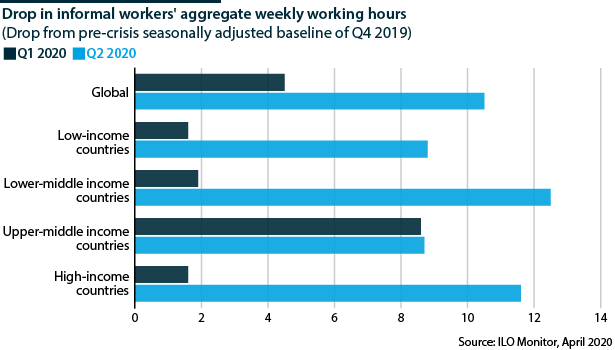

According to ILO data, of the 2 billion informal workers, 1.56 billion have been seriously affected by the pandemic. Informal workers worked 10.5 fewer hours in the second quarter of 2020 and 4.5 hours fewer in the first quarter, compared to the last quarter of 2019.

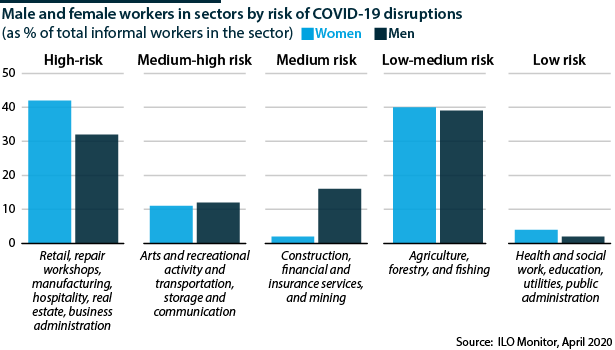

Informal women workers have been harder hit than men owing to their sectoral concentration. Early on in the pandemic, the ILO estimated that 42% of women workers compared to 32% of men were in sectors of the informal economy that were significantly affected by such COVID-19 containment measures as lockdowns, and were at high risk of a severe decline in economic output.

In 2020, women experienced 5.0% employment loss globally, against 3.9% for men. Women across all regions have been more likely than men to drop out of the labour force. This is accompanied by a high associated risk of long-term labour market detachment for women, young people, the low-paid and low-skilled, many of whom are found in the informal economy. Indeed, by end-2020, according to research by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), globally and across all country income groups the crisis had reversed improvements in female force participation made over preceding decades.

Moreover, most jobs in the informal economy lack basic protections, including social protection: informal workers often have no income replacement support in the case of loss of employment or sickness.

Immediate damage

For many female informal workers, containment measures had immediate consequences.

Sudden and protracted lockdowns left many of those earning a daily living in informal jobs with no possibility for working from home in poverty or destitution. Yet as the initial widespread lockdowns lifted, many female informal workers have continued their work in sectors increasingly deemed 'essential' but characterised by precarious, hazardous, unprotected and low pay. Economic necessity and the persistent effects of inequality leave many no other choice.

Research has found many domestic workers -- many of whom are informal women workers experiencing poor working conditions -- burdened with extra workloads by employers ever-more conscious of hygiene measures, without extra compensation. Others have been dismissed without compensation, sometimes because they are stigmatised as potential disease transmitters.

Female informal workers are essential to urban food supply chains in many low- and middle-income countries, including street vendors and market traders. Yet their workplace puts them at risk of catching the virus, with inadequate access to water or sanitary facilities, and little possibility to practice social distancing. Notably, in Zimbabwe, street vendors defying lockdown to work owing to economic destitution had their stalls destroyed by the authorities and many were arrested.

Social impact

The impact on the labour market has been more severe for women, in both developing (see LATIN AMERICA: Pandemic will worsen gender inequality - March 22, 2021) and developed economies (see UNITED STATES: Uneven recovery risks wider gender gaps - March 26, 2021).

Unpaid care

The pandemic has exacerbated the pre-existing unequal distribution of unpaid care disproportionately carried out by women. UN data show that this has increased because of the presence of children in the household due to school closures, illness among family members, home-schooling, cooking and cleaning. For example, in South Africa, among informal employees, 70% of women (50% of men) reported increased childcare responsibilities in April 2020, following school closures.

For informal female workers, this intensification of household responsibility has coincided with the significant labour market shock disproportionately affecting them, resulting in fewer economic resources available to meet family needs. This has been further compounded by the fact that these women typically have fewer coping strategies, for example access to savings and other assets.

Well-being decline

Consequently, women's well-being has suffered acutely during the crisis.

- Heightened risks of food insecurity and malnutrition are faced by pregnant and nursing women and children, and women and girls are more likely to reduce their food consumption within the household.

- Lockdowns have limited access to healthcare, family planning and schools, with funding diverted away from maternity and sexual and reproductive health needs, including contraceptives.

- There have been widespread reports of increased violence against women and girls, exacerbated by lockdowns, school closures and economic crisis (see MEXICO: Domestic violence moves to prove insufficient - January 11, 2021).

Social protection is often inaccessible to women in the informal economy

Policy measures

Policy measures taken in response to the crisis have been unprecedented in number and scope. As the UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights has pointed out, the extent of the rapid response by governments to cushion the shock of the pandemic shows that positive change can happen fast with political will.

In September 2020, the World Bank reported that there had already been almost 1,200 new or adapted social protection and labour market-related interventions in response to the crisis.

Yet women in the informal economy have been left out as a result of gender-blind policy design.

Problems of being gender-blind

As of March 2021, the UNDP-UN Women COVID-19 Global Gender Response Tracker analysis measured only 41% of global social protection and jobs responses as 'gender-sensitive' -- that is, targeting women's economic security or addressing the rise in unpaid care work.

Critically, this refers to policies targeted at all women globally. Yet women are not a homogeneous category. It has long been established that female informal workers are among the groups least covered by social insurance or poverty-targeted social assistance schemes, leaving them and their families vulnerable to economic shocks. Despite immense need, this policy blind-spot did not change significantly during the current crisis.

Left out by design

According to a forthcoming ODI study, some policy measures have even left some female informal workers out by design. Notably, South Africa's social protection response has been called "among the boldest in the world". In March 2020, the government announced an extension of unemployment insurance though the COVID-19 Temporary Employee/Employer Relief Scheme (TERS). However, this employee-focused measure leaves informal workers out, with women doubly penalised by their under-representation in the formal economy.

To bridge the gap, a new COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress (COVID-19 SRD) grant was introduced, predominantly aimed at those aged 18-59 who are unemployed and ineligible to apply for other grants, claim unemployment insurance or receive any other state benefit.

However, for women there was a major problem. Many are named as the recipient of the government's Child Support Grant owing to their role as family caregivers -- particularly pertinent in South Africa, given the relatively high rate of female-headed households (37.9%). These women were therefore de facto excluded from applying for the COVID-19 SRD. Surveys suggested that by June 2020, only 34% of those who had been paid the SRD in June 2020 were women.

Therefore, women's individual entitlement to access income support was in practice limited by the design of the government's policies.

Few childcare options

Moreover, despite needing to work to ensure basic economic survival and with schools closed, many female informal workers were left without childcare owing to a lack of services and lockdowns limiting informal care options.

According to the UNDP-UN Women Tracker, only 40 social protection measures have focused on providing childcare services, including for essential workers, most of them in Europe. Supporting female informal workers' unpaid care loads remains far from a policy priority.

Multilateral effort

The informal economy has long been the focus of the global institutions -- and long-standing debates are more salient than ever in the wake of the pandemic.

Multilaterals have played an important but contested role during the pandemic

These institutions have paid particular emphasis on collecting and analysing data about the impact of the crisis on informal workers. The timely ILO statistical bulletins and World Bank and UNDP-UN Women Tracker initiatives have been particularly noteworthy in aiding the development of evidence-based policy.

Moreover, multilateral institutions have called on governments to collaborate on policy efforts and funding in order to prevent further backsliding of UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which include targets to increase labour market formality and empower women (see PROSPECTS 2021: SDGs outlook - November 13, 2020).

However, even before the pandemic, different starting points, policy priorities and accountability between countries meant that implementation of SDG commitments varied significantly. Consequently, their value in creating a benchmark for improving conditions in the informal economy will continue to vary by context and country (see INTERNATIONAL: Developing nations risk a weak recovery - March 26, 2021).

Fundamental divergence

Moreover, a more fundamental issue is at stake. Multilateral institutions vary significantly in their view of the underlying causes of formality and why, whether and how to tackle it:

- The ILO advocates 'incremental formalisation' focused on improving workers' rights, conditions and access to social protection, and broadly supports increased labour regulation as a means to achieve this, for example by ensuring businesses and government support access to social safety nets.

- By contrast, other major international financial institutions have long argued that too much regulation hinders the formalisation of enterprise and have advocated decoupling labour and social protection. The World Bank's 2019 'The Changing Nature of Work' report, for example, posits that informality can be reduced through the wide-scale deregulation of business to reduce informality. It recommends reducing obligations to contribute to employer-financed social protection.

This divergence leads to a tension both on the global stage and at country level, where multilateral organisations can have a significant role in informing and influencing policy processes.

This divergence matters in the pandemic context. The unprecedented efforts of many governments to recognise the realities of informal workers' highly precarious economic situation and extend income and other in-kind support via the social protection system could appear to herald a new focus on rights, equality and understanding of those long 'left behind' by public policy. This approach would favour the ILO's recommendations and experts ready to support governments to improve protections for informal workers.

However, at the same time, the scale of the pandemic-induced economic crisis reduces the fiscal space for government spending, including for social programmes, and increases the need to create an enabling environment for private sector development. Indeed, multilateral institutions such as the IMF which are providing emergency funding to struggling countries are recommending fiscal belt-tightening. For example, the recently announced IMF loan to Kenya promises short-term additional spending on health and social protection but recommends fiscal consolidation in the medium term.

Outlook

The pandemic crisis has widened decades-long gender gaps experienced by women in the informal economy, in areas ranging from the quality of work and working conditions to access to social protections and the burden of unpaid care work. These gaps will be difficult to narrow as long as gender-blind economic policymaking continues during the current crisis, and during the post-crisis recovery period.