Brazil deforestation pressures will mount at COP26

Government policy will face renewed scrutiny amid reports that parts of Amazonia now emit more carbon than they capture

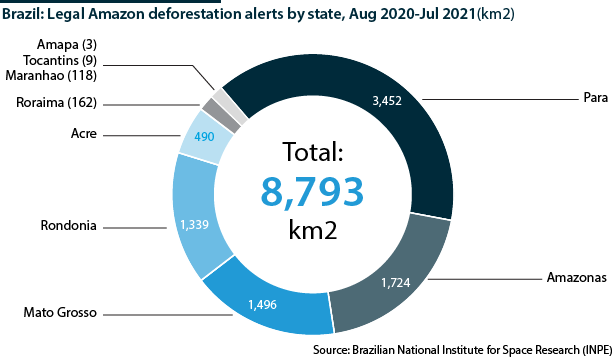

A new World Meterological Organization report indicates that part of the Amazon rainforest now emits carbon rather than absorbing it, due to deforestation and fires. During last month’s UN General Assembly, President Jair Bolsonaro unsuccessfully argued that his government was controlling deforestation in the Amazon region. Reports indicate that between August 2020 and July 2021, nearly 8,800 square kilometres (km2) of forest were cut down.

What next

Data showing that Amazon rainforest carbon release is now higher than absorption raise further concerns about the achievement of climate goals and environmental sustainability. At the COP26 climate conference, the Brazilian delegation led by Environment Minister Joaquim Leite will push for international support. In the face of significant potential losses, major Brazilian businesses have come out in favour of a change in environmental policy.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Despite stronger international pressure, the outlook for forest preservation is alarming absent a well-structured policy for Amazonia.

- Major Brazilian business sectors will face significant risks from international climate pushback without policy improvements.

- Brazil will argue for greater international assistance to offset the costs of climate mitigation policies.

Analysis

Several studies have been released highlighting global concerns regarding the impact of ongoing Amazon deforestation on global warming and climate change goals, including warnings that the Amazon rainforest may already be releasing more carbon than it is capturing, as a result of deforestation and unsustainable practices.

Bolsonaro's government has encouraged mineral, timber extraction, livestock and agricultural activities in forest areas. Protection and oversight bodies, including the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio) and the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama), have also suffered from federal budget cuts in recent years.

High deforestation rates and, therefore, sharp criticism regarding environmental policy during former Environment Minister Ricardo Salles's tenure led to his replacement in late June. However, little has changed under Leite, despite his making fewer controversial declarations than his predecessor.

Leite previously worked in the ministry, leading the Amazonia and Environmental Services Secretariat, and for more than 20 years was a member of the Brazilian Rural Society's council, an entity supporting agribusiness and the congressional Parliamentary Agricultural Front.

Despite Bolsonaro's General Assembly speech, his government's actions show no clear commitment to targets such as emissions and deforestation reduction, but instead short-term responses to mounting national and international pressure (see BRAZIL: New environmental promises clash with policy - May 6, 2021). Not by chance, the Austrian NGO AllRise recently presented a complaint against Bolsonaro before the International Criminal Court (ICC) alleging "crimes against humanity" related to deforestation (see BRAZIL: Bolsonaro faces new environmental pushback - October 12, 2021).

Amazon deforestation

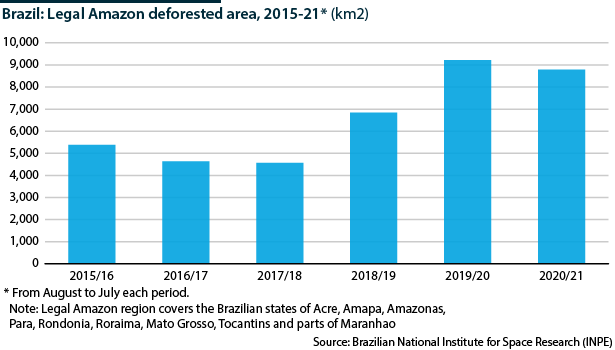

Deforestation rates in the 'Legal Amazon' (which covers the states of Acre, Amapa, Amazonas, Para, Rondonia, Roraima, Mato Grosso, Tocantins and parts of Maranhao) have increased significantly since Bolsonaro took office in 2019 (see BRAZIL: Global and domestic Amazon pressures will rise - September 14, 2020).

18,000 km2

> Area deforested in past two years

The previous downward trend has been reversed since the 2018/19 period, reaching its highest level from August 2019 to July 2020. Amid strong national and international pressure, official figures showed a small reduction in 2020/21 but remained extremely high. The area deforested during the last two annual periods totalled over 18,000 km2, according to data from the DETER system (System for Detection of Deforestation in Real Time) released by the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE).

According to Brazilian research institute Imazon, deforestation in Legal Amazon from August 2020 to July 2021 was even higher, equivalent to 10,476 km2, the worst in a decade.

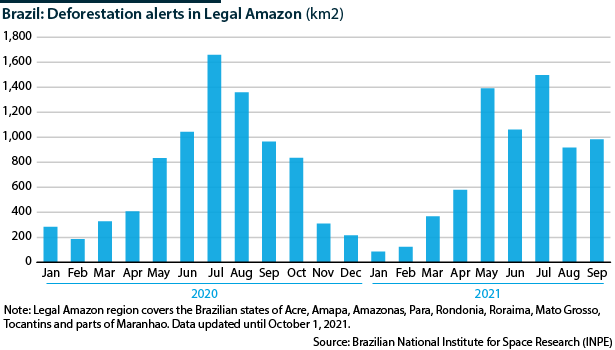

Monthly data show a seasonal pattern, with more alerts during the mid-year dry period, particularly between May and September. Despite that, alerts have increased sharply since March this year, even faster than in 2020. In May alone, the deforested area was estimated at around 1,390 km2.

Although figures declined after peaking in July 2020, they remain high. Last month, an area of almost 985 km2 was deforested in Amazonia, a 2% increase year-on-year.

Figures by state

Deforestation data show that nearly 40% of the more than 8,790 km2 area damaged from August 2020 to July 2021 was in the state of Para, followed by Amazonas (19.6%), Mato Grosso (17.0%), and Rondonia (15.2%), accounting for over 90% of deforestation in Legal Amazon during this period. Amazonas, Para and Mato Grosso are the three largest Brazilian states by area (see BRAZIL: Agribusiness focus risks rise in deforestation - July 23, 2019).

There have been increasing fires and deforestation in the so-called "Amacro" region, the tri-border area between the states of Amazonas, Acre and Rondonia. At least two federal police actions were recently launched against land grabbers in that region. The territory is seen to be a new agricultural and mineral frontier, beyond traditional areas in Para and Mato Grosso states.

Promises at COP26

Various promises are expected at COP26, starting in Glasgow on October 31.

Although Vice-President Hamilton Mourao planned to head the Brazilian delegation in his capacity as leader of the Legal Amazon National Council, Bolsonaro has chosen Leite instead. Leite has already pronounced that Brazil is committed to eliminating illegal deforestation by 2030 and reaching carbon neutrality by 2050, trying to demonstrate that Brazil can fight climate change while remaining a key agricultural powerhouse:

- A draft law presented by Tocantins Senator Katia Abreu and currently before Congress proposes that Brazil should establish 2025 instead of 2030 as a target date for reducing emissions and eliminating illegal deforestation.

- In a recent IMF meeting, Finance Minister Paulo Guedes said that Brazil is about to launch a USD2.5bn green infrastructure programme, whose details may be presented at COP26.

According to Leite, Brazil will seek consensus on the volume of financing for mitigation and reforestation, demanding around USD100bn dollars per year from developed countries to initiatives in the developing world -- a significant share of which would likely be earmarked for Brazil.

Calling for international financial aid may be Brazil's COP26 bargaining chip

However, reversing international scepticism about Brazilian goals may require greater efforts.

Business risks

Large food suppliers are concerned about the traceability and decarbonisation of their supply chains. Brazilian local producers are now facing both national and international pressure to certify that raw materials follow environmental standards and, in particular, do not come from deforested areas. Meat-packing firms are among such supply chains:

- The National Confederation of Industry has announced that it will present successful business initiatives for environmental sustainability at COP26.

- The Brazilian Business Council for Sustainable Development has delivered to Foreign Minister Carlos Franca a document, signed by more than 100 companies, urging Brazil to support the regulation of carbon markets at COP26.

However, the lack of policy commitment to curbing deforestation may lead to heavy losses in commodity markets, in which Brazil is one of the world's largest players.

Indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples have been severely affected by the dismantling of environmental rules and increasing invasions of protected territories. Not only has COVID-19 disproportionally damaged local communities in remote regions (see BRAZIL: Policy shortfalls will see new COVID outbreaks - February 22, 2021), it has also boosted illegal activities carried out by land grabbers and mining prospectors.

In addition, a Supreme Court decision on a land demarcation bill (the so-called 'time limit' bill, PL490) could prove vastly significant. If, as agribusiness has urged, the Court rules that indigenous peoples have no rights to lands if they cannot prove they already occupied those lands when the 1988 constitution came into force, this would allow for new claims and occupations of those lands. After several delays, the Court last month shelved the case indefinitely.