Turkey's economic policy shift is not worth the risks

Letting the lira slide and prices soar may do little for growth and augments the risk of an eventual crisis

The lira is trading at about TRY14.70:USD1 ahead of tomorrow’s Central Bank (TCMB) rate-setting meeting. The lira’s collapse has only fortified President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s adherence to unorthodox low-interest-rate policies. Rather than changing course, Erdogan has publicly declared a “new economic policy”, stating more than once, “We know what we’re doing”.

What next

The lira will remain weak and inflation high, yet the boost to economic activity will be limited and the current-account deficit may narrow no further. Erdogan and his administration are unlikely to do an about-turn and may take additional measures that could further increase the possibility of eventual financial, fiscal and/or balance-of-payments crisis.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Not everyone will be compensated for inflation, and discontent will persist, along with the need for other ploys to win elections in 2023.

- High inflation and unpredictable government policy will add to the challenges of doing business.

- Ankara may continue to develop relations with countries able to provide funds and investment, such as Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.

Analysis

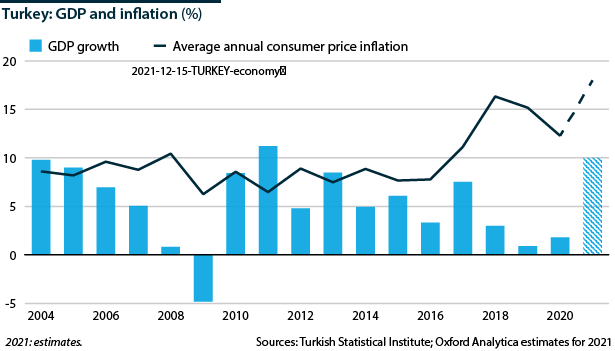

In September, October and November, Erdogan imposed interest-rate cuts on the TCMB in spite of rising inflation and a weakening lira. The key policy rate fell from 19% to 15%.

The lira has crashed. Consumer price inflation has accelerated, reaching 21.3% in November, and is set to rise higher. The population is alarmed.

Erdogan's interest-rate concerns have evolved into a broader economic-policy discourse

New policy

The president and his supporters present his policy thus:

- 'High-interest, low-exchange-rate' policies favouring international financial investors have hobbled and skewed economic growth. Attention should be paid to investment and production; that requires low interest rates.

- Output growth and a competitive lira will boost exports, narrowing the perennial current-account deficit. This will take pressure off the lira, halt imported inflation and increase Turkey's economic independence.

- The recent exchange-rate slide is a speculative attack. The inflation surge is a temporary consequence of this volatility, rising global prices, hoarding and (in Erdogan's opinion) high interest rates.

- Growth-oriented policies will boost employment so that everyone shares in the benefits. Raising public-sector pay and the minimum wage will protect the public against inflation.

Origins

Erdogan has long opposed high interest rates out of religious scruples and a preoccupation with cheap credit for business.

Attempts to implement low-interest-rate policies in 2018 and 2020 were interrupted by TCMB rate hikes. The governors responsible were sacked and the cycle resumed again.

Such figures as Berat Albayrak, Erdogan's son-in-law and a former treasury and finance minister, and current TCMB Governor Sahap Kavcioglu, have supported low rates and helped develop a broader discourse around them (see TURKEY: Early elections may forestall deterioration - March 24, 2021).

Recently appointed Treasury and Finance Minister Nureddin Nebati (an associate of Albayrak) has said this time they were determined to pursue the low-interest-rate policy they had tried and failed to implement since 2013.

Further U-turns are unlikely, now that orthodox ruling party cadres have been side-lined and Erdogan has declared an "economic war of independence".

Benefits

The president appears to be relying on the new policies ahead of presidential and parliamentary elections due in 2023 (see PROSPECTS 2022: Turkey - November 17, 2021).

New policy's benefits are probably few; drawbacks and risks are substantial

Interest rates

Given high inflationary expectations and widespread scepticism about the new policy, TCMB rate cuts may not push market interest rates much lower and credit growth may be slower than expected. So far, bank deposit and mortgage rates have fallen more than other credit rates (with state banks leading the way), while lira-denominated government bond yields have risen.

Growth

Even if credit expansion is slow, sub-inflation deposit rates will distort economic behaviour, deter savings and encourage demand in such sectors as real estate and durable goods. The government target of 5% GDP growth in 2022 is very ambitious given rising prices, potentially weaker external demand, supply-chain bottlenecks and the challenges of doing business (let alone investing) in such unpredictable conditions.

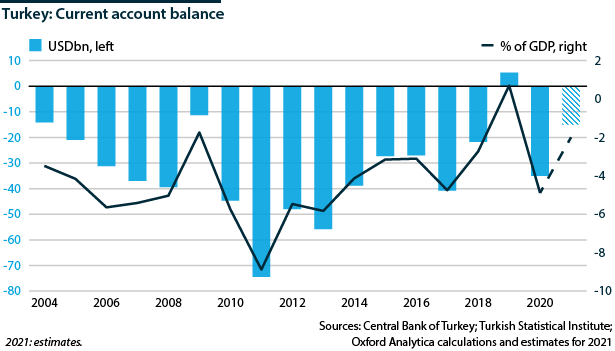

Current account

Lira weakness may boost exports (and tourism) to some extent and will certainly deter imports (see TURKEY: Teetering on the brink of crisis despite trade - December 9, 2021). However, energy and many other items must be imported, regardless of the exchange rate, to keep the wheels turning.

The current-account deficit narrowed in 2021 despite rapid economic growth, and 2022 may see tourism recover further. Even so, pro-growth policies may require a deficit of 2-3% of GDP.

Drawbacks

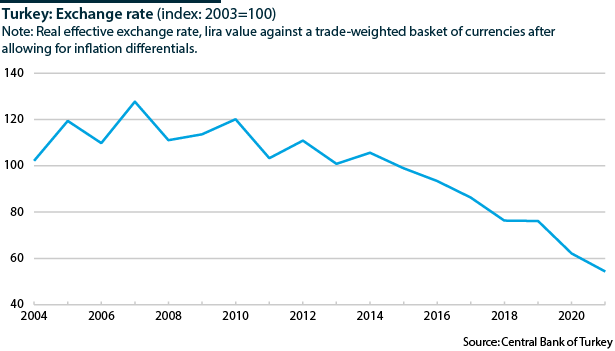

The ultra-weak lira is unlikely to recover much.

Exchange rate

Nominal depreciation could continue. After years of lira weakness and volatility, residents are unlikely to sell their substantial foreign exchange savings (more than 60% of bank accounts are foreign-currency-denominated), even at today's rates.

TCMB foreign-exchange sales have had little impact, and more sustained interventions would only aggravate risk perceptions. Gross foreign exchange reserves total USD85bn (excluding gold); net reserves are minimal.

Inflation

The lira's collapse will raise domestic prices of imported/internationally traded goods, and goods and services with imported components, in the short term. Inflationary expectations will remain high. Flatter global commodity prices would help, but adjusting wages and pensions for inflation could normalise rates of over 20%.

Debt

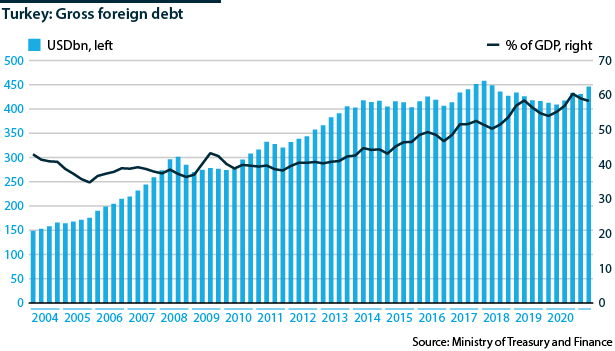

Lira weakness has increased substantial private-sector and government foreign/foreign-currency debts more than revenues. The higher corporate debt burden creates added risk for banks.

Higher government debt repayments, compounded by higher borrowing costs, will widen the budget deficit. Public debt has been low at about 40% of GDP, but 60% of central government debt is foreign-denominated.

Capital flows

Foreign-exchange reserve stability depends on attracting sufficient external financing to service a foreign debt (public and private) of around 60% of GDP in addition to financing the current-account deficit.

Much of the debt may be rolled over routinely, and low prices due to lira weakness may attract foreign investment in equity and real estate. However, Turkey's borrowing costs have risen, its credit ratings are likely to be downgraded, relations with the West are poor and global liquidity may tighten.

Many funds and banks will therefore wish to reduce their exposure to Turkey. Speculation about a possible foreign-currency shortage will persist.

Next steps

If Erdogan is not satisfied with, or wishes to reinforce, the new policy, he could take additional steps that would exacerbate the drawbacks and risks.

Additional measures could damage banks, the public finances and the business environment

More rate cuts

Markets are braced for a further cut to 14% tomorrow but hope it will be the last.

Obliging banks to increase low-cost lending

The banks are generally strong, but state banks may need a capital injection. Private banks may require government support if credit quality worsens, profitability falls and market risk increases.

Increased public expenditure/tax cuts

The government is already subsidising household gas prices and waiving taxes on motor fuels to limit price increases. Such policies may be extended. Pensions and public-sector pay are expected to rise sharply at New Year. Tax breaks may help offset a minimum-wage increase for employers. Social benefits may go up too.

The government could subsidise bank loans to encourage investment and production. Looser policies and high debt-servicing costs could take the public-sector deficit past the envisaged 3.7% of GDP in 2022, adding to borrowing needs.

Authoritarian controls

Market inspectors are watching for 'exorbitant' pricing. The Competition Board has fined supermarkets publicly criticised by Erdogan. Legislation against hoarding is to be strengthened.

Import restrictions or disincentives for holding foreign exchange may be considered, although the latter would risk capital flight.