Iran nuclear talks approach a point of crisis

Despite a new tone of optimism, there has been little real progress so far in the Vienna negotiations

Foreign minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian today emphasised that Iran had offered “constructive” proposals in negotiations in Vienna over restoring the defunct 2015 Iran nuclear deal known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). He denied Iran was playing for time. Political negotiators have now returned to the talks after consulting with their capitals while technical sessions continued, and the tone on Iran’s side is optimistic. However, Washington is concerned about the lack of concrete progress, and is setting a short deadline for an agreement.

What next

The United States will look at alternative ways of staving off an Iranian nuclear weapon capability, starting with more sanctions. Beyond this, 'kinetic' ‘Plan B’ options (involving military or covert action) all entail significant uncertainties. The parties are thus likely to stay at the negotiating table beyond the purported deadline as long as any hope remains. Israel may again seek to sabotage Iranian nuclear facilities, but not during ongoing talks.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Washington will be reluctant to undercut its leverage by relaxing secondary sanctions to allow unfreezing of Iran's funds in South Korea.

- If the JCPOA is restored, Western states would seek an extra deal to extend the limits on enrichment and address Iran’s missile programme.

- Tehran would resist discussing missiles in a follow-on deal, but new concessions such as trade by US companies might be an inducement.

Analysis

After months of stalling and floating new demands, Iran's conservative government under President Ibrahim Raisi in December finally agreed to negotiate from the starting point of where the Vienna talks broke off in June 2021 under the previous centrist administration.

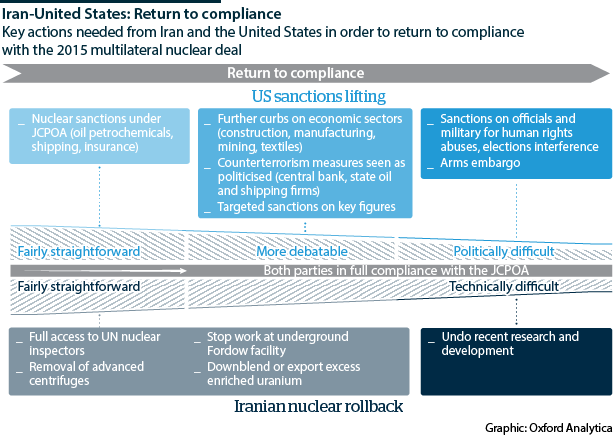

The participants have exchanged texts outlining areas of difference (see IRAN/US: Staged nuclear deal return faces challenges - February 4, 2021). However, except on minor issues, these gaps are not yet being bridged.

Sanctions disputes

Recent rounds of negotiation have focused on Iran's demands for sanctions relief (see IRAN: The new president has few economic options - October 19, 2021). Tehran continues to insist that in addition to the nuclear-related sanctions associated with the original deal, the United States should lift over 500 sanctions imposed under former US President Donald Trump.

President Joe Biden is reluctant to remove sanctions that had nothing to do with the JCPOA and that would not impede its implementation, such as those responding to Iranian human rights violations. However, Washington would be prepared to negotiate on the degree of sanctions lift if Iran moved away from its all-or-nothing approach.

Tehran also demands that the lifting of sanctions should first be verified, for instance through the return of actual oil sales. Meeting this demand would have to be done in a way that does not preclude simultaneous return to JCPOA compliance, since if he lifts sanctions, Biden has to be able to certify to Congress every 90 days that Iran is meeting its nuclear commitments. There are some suggestions on possible compromises -- for instance, if Washington first allowed contracts to be concluded.

The shadow of 2024 is already looming

Most intractable is Iran's demand for guarantees that the United States will not pull out of the deal again while Iran remains in compliance. Biden has given a political pledge to that effect, but he faces legal constraints and cannot bind his successor.

Realistically, Tehran likely realises it will have to settle for exhortative language or proxy commitments to protect longer-term transactions (see IRAN: US deal's investment impact may be limited - July 14, 2021). Examples might include political risk insurance, international arbitration or even a promise by JCPOA signatories to support Iran's accession to the WTO, which would allow it to access that dispute settlement mechanism to challenge US sanctions.

Nuclear rollback

A deal in Vienna will require Iran to reverse its nuclear progress (see IRAN/US: Nuclear deal miscalculation risks are rising - September 17, 2021).

Since breaking out of the JCPOA restraints in mid-2019, Tehran has increased its stockpile of enriched uranium to around ten times the limit, while its enrichment level is now 16 times above the 3.67% limit. It has also installed hundreds of advanced centrifuges able to enrich uranium several times faster than the machines it used under the deal.

Notably, it has produced about 25 kilograms of 60% highly enriched uranium (HEU), a short step away from the 90% level regarded as weapons-grade -- a US and Israeli red line. Although the head of Iran's Atomic Energy Organisation has said enrichment will not exceed 60% even if US sanctions are not lifted, there is no doubting Iran's ability to do so.

With these advances, Iran could theoretically now produce enough HEU for a nuclear weapon in as little as three weeks by some calculations (the 'break-out time'). Estimates of how long it would then take to produce a weapon, if Tehran chose to do so, vary from six to 24 months.

The JCPOA's goal was to keep the break-out time to twelve months or more. Even if Iran were to return to all limits and ship its excess uranium stockpile to Russia, the development of advanced centrifuges could make it impossible to extend the break-out time back to one year.

Destroying the advanced centrifuges would bring that goal closer, but Iran insists that any centrifuges removed from production should only be stored within the country, as per the JCPOA. A feasible compromise might be to keep the machines but to demolish the piping and other infrastructure.

Agreement prospects

Meanwhile, Washington repeatedly warns that time is running out, as Iran's nuclear advances over the past year make it increasingly impossible to return to the original conditions of the deal. Moreover, the JCPOA's own 'sunset clauses', which mean many constraints on Iran expire beginning in 2026, are drawing closer, diminishing the nonproliferation benefits.

A mooted US February deadline could spark a crisis

US officials have posited a loose early February deadline for deciding whether there is sufficient chance of reaching agreement by the end of March. Unlless real progress is made by then, Washington is discussing with London the possibility that the latter might use its right as a signatory to trigger 'snap-back' UN sanctions.

China and Russia would resist implementing such measures, limiting the additional economic impact (see IRAN/CHINA: Beijing will not pressure Tehran on deal - November 29, 2021). Nonetheless, Iran would suffer from a renewed unfavourable legal status and the political and psychological impact of once again being an official international pariah.

Plan B

Such coercive diplomacy following on from Trump's 'maximum pressure' would likely prompt Iran to end all talks -- but some US officials may view this as a necessary outcome if Tehran is going to continue moving toward a weapons capability. Failing a deal, the United States and Israel are considering military and covert options, which they assess might conceivably induce Iran at least to accept some sort of ceasefire agreement to stop the escalation.

However, media reports from Israel in December reflected pessimism that Israel on its own could effectively destroy Iran's nuclear infrastructure. Israeli officials also acknowledge that a frontal attack on Iranian facilities would likely unleash counter-attacks, including from Iran's ally Hezbollah and its some 150,000 increasingly accurate rockets (see IRAN/ISRAEL: Conflict path will depend on US talks - June 4, 2021).

Israeli air attacks on the Natanz enrichment plant and sabotage and commando attacks on the more deeply buried enrichment facility at Fordow could at most set back Iranian nuclear advances to buy time -- and would risk embarrassing deaths or even capture of Israeli personnel. Moreover, Iran has responded to past Israeli nuclear sabotage operations by increasing uranium enrichment.

On balance, diplomacy is thus likely to remain the preferred option.