Globalisation will evolve rather than reverse

Fears that several decades of globalisation will unravel have risen since the Ukraine war but such fears are premature

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is the fourth major event in the last 15 years to trigger widespread concerns that globalisation is unravelling. The global economy is unquestionably undergoing a period of structural transformation shaped by the war and an acceleration of pre-existing dynamics. These changes will create new winners and losers, but will do so without upending the geopolitical status quo or drastically rolling back international economic interdependence.

What next

The contemporary form of globalisation will persist beyond the war and pandemic, instead experiencing a comparatively minor rebalancing to bolster supply chain resilience and national self-sufficiency in critical components and agricultural products. The war will nevertheless reduce the capacity for collective action on a global scale. The most significant long-term threats to globalisation remain the climate crisis and concurrent rise in autocracy and illiberalism.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Growth in goods trade and foreign direct investment has been slowing since 2008-09 but flows of data, capital and services will rise ahead.

- Re-shoring will rise as nations aim for self sufficiency, but slowly; every industrial economy bar China grew more import-dependent in 2020.

- Global trade will continue to rely on three hubs: Europe, led by Germany; North America, led by the United States; and Asia, led by China.

Analysis

Larry Fink, BlackRock CEO, last month proclaimed the invasion of Ukraine marked "an end to the globalisation we have experienced over the last three decades" in his annual letter to shareholders. Yet such claims -- which echo responses to the pandemic, the US-China trade war and the 2008-09 financial crisis -- remain premature.

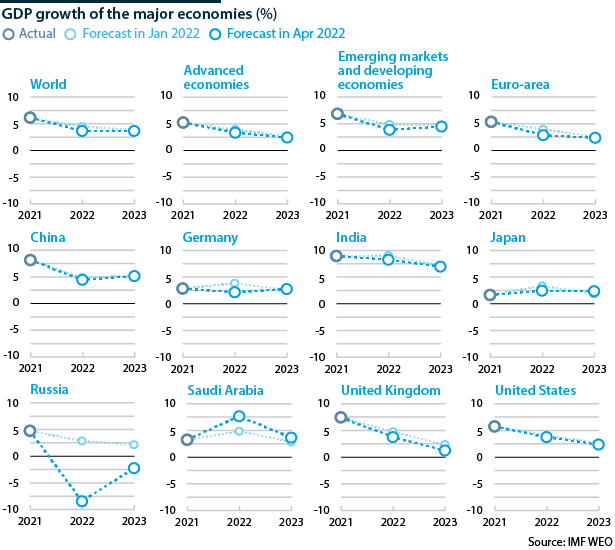

The incursion is destabilising the international economic landscape during a period of acute fragility. The direct consequences and spillover effects will reverberate for years, and threaten to trigger interlinked economic and humanitarian crises (see INTERNATIONAL: Geopolitical strife cuts potential GDP - April 21, 2022). The United States and its allies retaliated against Russia by imposing crushing sanctions and export controls, ejecting the world's eleventh-largest economy from the networks that bind globalisation and precipitating a wave of private sector divestment that are combining to force a projected 8.5% contraction on Russia in 2022 alongside a projected 20% contraction in Ukraine.

'De-globalisation' dynamics

The war is slowing global growth and aggravating inflationary pressures by increasing commodity prices and exacerbating supply chain disruptions at the same time as China imposes its largest-ever COVID-19 lockdowns. High oil prices could further increase if the war expands -- a diminishing but real possibility that could be prompted by further NATO expansion -- or if nuclear negotiations with Iran collapse. Sudden spikes would increase pressure on Western economies, in particular Germany and the United Kingdom, to renounce plans to ban Russian energy imports. Rising food prices are fomenting political instability in some developing economies, in particular those dependent on commodity imports, which would be compounded by aggressive Federal Reserve monetary tightening.

These shocks are reinforcing normative and political shifts toward greater national self-sufficiency and reduced corporate risk exposure that predated the conflict. In the United States, the Biden administration is advocating the 'friend-shoring' of supply chains, increasing domestic content requirements for federal infrastructure projects, and incentivising domestic production of critical components. European leaders are working toward digital and semiconductor sovereignty and investing in their capacity to mine lithium and other materials required for the green transition. Beijing is doubling down on its push for self-reliance in key technologies and agriculture, reducing exposure to US Treasuries by recycling its surpluses into other asset classes, and trying to build out viable alternatives to existing financial institutions such as the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System.

Globalisation evolving, not reversing

Russian isolation underscores the costs of exclusion from global trade and financial networks

These disintegrative dynamics nevertheless do not portend widespread deglobalisation. Russian isolation, if anything, underscores the costs of exclusion from the tightly integrated global trade and financial networks to other potential aggressors. The risk of the global economy fracturing into two blocs organised around the United States and China is similarly overstated.

Trade resilience

International trade proved surprisingly resilient during the pandemic despite the effects of lockdowns on supply chains (see INTERNATIONAL: Pandemic could change trade and FDI - February 26, 2021). Moreover, the majority of Western multinationals remain committed to the Chinese market, with little reshoring or diversification actually occurring despite rhetorical commitments. For example, 83% of US firms in China are not considering relocating their manufacturing or sourcing, according to the American Chamber of Commerce in China's 2022 Business Climate Survey published last month.

Furthermore, globalisation is already constructed on regional commercial platforms and, as evidenced by the fragmented Russia sanctions regime, many countries would continue to engage both blocs even after a more severe US-China rupture. Despite the headlines, some countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America have maintained a neutral stance or continue engaging with Russia. Building a unified alliance against China would prove far more difficult given its larger economic and political influence.

Global trade proved resilient to the pandemic and to US-China tensions

Capital, data and services flows will increase

Global flows of capital, data, and services will also offset slower growth of goods trade over the longer run. Western investment banks and asset managers continue to expand their footprint in China -- a long-term commitment that has deepened in recent years, and will outlast the recent surge in foreign outflows.

Cross-border data flows continue to grow strongly as the backbone of the 21st century global economy despite growth in localisation policies. Services trade is expected to rebound sharply following pandemic-driven sluggishness driven by the collapse of international travel.

Globalisation has firm foundations

The US-led response to Russia's incursion has illuminated both the hegemonic foundations of contemporary globalisation and the staying power of its foundations, including the global dollar system. Dollar dominance, despite tentative warnings from the IMF and wider media debate, is not under serious threat due to a fundamental lack of alternatives and self-reinforcing feedback cycles that sustain its supremacy. From a broader geopolitical perspective, the war has reinforced the coherence of the Western coalition while highlighting cracks in the China-Russia relationship and the comparative inability of Russia to project its power internationally.

Outlook

Globalisation is evolving in its post-financial crisis form rather than entering a new period. Growth in global trade and financial flows already levelled off after 2008 and can be expected to remain relatively stable with deepening interdependence driven predominantly by cross-border data flows. Manufacturers are likely to explore supply chain diversification and streamlining but will continue to resist pressures for more fundamental restructuring of these complex commercial networks.

The most substantial short-term changes will be political, which are also the leading risk for a major breakdown. Rising geopolitical tensions predating the war are complicating efforts to modernise the global trade and financial architecture, leading to a proliferation of calls for plurilateral solutions to global problems. This reduced capacity for cohesive international action presents the most significant threat to globalisation, particularly by diminishing the chances of meaningful collective action to combat the climate crisis.

US-China tensions will remain the most dangerous fault line in the global economy, and may be aggravated to critical levels by either the resurgence of economic nationalism in the West (for example the America First agenda Donald Trump would follow if re-elected in 2024), or deepening autocracy in China. A Chinese military assault on Taiwan -- a remote but realistic prospect -- would prompt a corporate and investor stampede. Only direct US-China conflict would be likely to trigger a complete disintegration of the global economy.