US nuclear 'fail-safe' thinking may interest Russia

Kremlin rhetoric has dimmed prospects for arms control but a US review of 'fail-safe' mechanisms offers scope for talks

Aggressive Kremlin rhetoric about possible use of nuclear weapons has heightened immediate risks and dimmed the prospects for negotiations. Russia has cancelled talks on reviving mutual inspections under the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START). As treaty negotiations stall, President Joe Biden's administration has begun a congressionally mandated review of 'fail-safe' steps to prevent accidental nuclear use.

What next

In an adverse climate for arms control discussions, the US review offers a path to discussing risk reduction measures with other nuclear powers. Under current geopolitical circumstances, this seems unlikely, but such discussions may be more straightforward than progress towards an all-new treaty to replace New START, where Moscow is being deliberately obstructive.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Whenever Moscow hints at nuclear arms use, Washington will warn it of catastrophic consequences.

- Biden may take executive action to place guardrails around US presidents' sole authority to order a nuclear strike.

- Progress on the review will require top-down leadership from the president and National Security Council.

Analysis

When Biden entered office two years ago, he and Putin swiftly extended New START for the maximum five years permitted.

After protracted argument under Donald Trump's presidency, both Washington and Moscow agreed to a simple extension without additional demands to complicate renewal (see RUSSIA/US: Arms treaty deal will help broader dialogue - January 19, 2021).

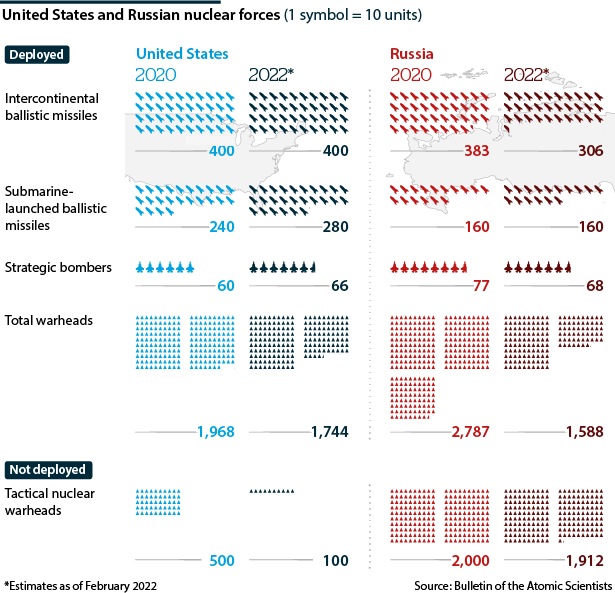

New START's ceiling on the number of deployed nuclear warheads, long-range missiles and bombers and its extensive verification provisions remain in place.

Over the next year, there were further positive developments.

Biden and Putin met in Geneva in June 2021 and agreed to launch a bilateral Strategic Stability Dialogue to lay the groundwork for the next agreement (see RUSSIA: Dialogue seems modest but has grand ambitions - August 10, 2021 and see RUSSIA/US: Summit will not be a watershed moment - May 19, 2021).

In January 2022, the leaders of all five nuclear weapon states -- Russia, the United States, China, France and the United Kingdom -- released a joint statement affirming that "a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought".

Hopes dashed

The positive momentum did not last long.

Russia's February 2022 invasion of Ukraine derailed the Strategic Stability Process. Putin's subsequent semi-veiled threats to use nuclear weapons raised the spectre of broader conflict.

Discussions at the New START Bilateral Consultative Commission planned for end-November on resuming mutual inspections offered hope but never took place (see RUSSIA/US: Arms talks date signals greater confidence - November 11, 2022).

Inspections were suspended by mutual agreement at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic but Moscow refused to resume them last August.

Russia's foreign ministry made it clear that the November meeting was postponed due to deteriorating wider relations, blamed on Washington rather than the Ukraine invasion. A January 6 article in Russia's Kommersant newspaper argued that if Moscow made changes in US foreign policy (including on Ukraine) a precondition for arms talks, "no consultations on the treaty or on inspections will happen".

Moscow has tied arms control talks to wider relations with Washington

The war and Putin's nuclear hints have destroyed what looked like a promising foundation for risk-reduction initiatives and the trust needed to negotiate, sign and ratify an arms control treaty to replace New START.

Uncertainty about Russia's posture

Putin's repeated threats to use nuclear weapons, most recently in a September 30 speech, have raised concerns that he might suddenly order a nuclear strike if battlefield reverses continue.

The 'Foundations of State Policy on Nuclear Deterrence' from June 2020 says nuclear weapons can be used if Russia suffers "aggression" involving conventional weapons and its existence is in jeopardy. This implies that Russia views its nuclear arsenal as an integrated component of military escalation (see RUSSIA/UKRAINE: Nuclear strike more than empty threat - October 7, 2022).

Putin's characterisation of NATO rather than Ukraine as Russia's real adversary underlines the importance for members' security of US guarantees, including the nuclear umbrella.

Concerns about Russia's intentions sit against a backdrop of deeper mistrust. Moscow has long seen US anti-ballistic missile systems, especially in its vicinity, as a threat to its nuclear deterrent capability. Its asymmetric responses include hypersonic weapons designed to cut through US defences.

Risk reduction in lieu of treaties

New START expires in 2026, and other frameworks such as the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty and the Open Skies Treaty are dead. Unless circumstances change for the better, the prospects are dim for treaty-based nuclear threat reduction.

Progress may happen elsewhere: unilateral measures by nuclear powers or coordinated steps that do not require treaties. These might centre on stronger fail-safe measures to prevent unauthorised, inadvertent or mistaken use of a nuclear weapon. Such measures could be adopted unilaterally, as with the US review, and in concert with other nuclear states.

What fail-safe means

Fail-safe mechanisms could be built into nuclear policy and force posture in such areas as:

- unequivocal adoption of a 'no first use' policy;

- nuclear procedures, for example changing the process for authorising or executing a nuclear weapon launch; and

- the design of nuclear weapons and delivery systems, ensuring systems are built to prevent terrorists from using a stolen bomb and that a ballistic missile can be destroyed in flight if it is launched by mistake.

New review

In November 2021, former Senator Sam Nunn and former Secretary of Energy Ernest Moniz published an op-ed in the Washington Post calling on Biden to order a review aimed at strengthening fail-safe systems.

Congress mandated a review one month later. The Biden administration followed by including a commitment to a review in its Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) in October 2022 and tasked the RAND and MITRE non-profit organisations with leading the effort.

Nunn and Moniz flagged specific items such as:

- post-launch destruction for nuclear weapons or delivery systems;

- red lines prohibiting cyberattacks on certain nuclear-related assets and systems; and

- a joint data exchange sharing information from early warning systems.

The review's credibility will depend on its independence and on whether it covers all options, has a long time horizon, challenges existing assumptions and policies and includes technical, procedural and policy elements -- no one solution will suffice.

The lack of a national security process in the Trump administration and concerns about the president's sole authority to authorise a nuclear attack demonstrated the dangers of leaving this question unaddressed over decades. The review could shape new guidance on a decision-making process requiring consultation with relevant officials and congressional leaders where time permits.

Kirkpatrick Commission

The last such review was conducted in 1990-92, led by Jeane Kirkpatrick, a former US ambassador to the UN. Her independent commission recommended more than 50 specific steps to prevent accidental, mistaken or unauthorised use of a nuclear weapon.

The world has changed since the last US review

That review happened 30 years ago. Multiple developments have taken place since then, including:

- rapid modernisation of China's nuclear arsenal, until now overshadowed by US and Russian weapon numbers and capabilities (see CHINA: Nuclear weapons upgrades increase risks - January 12, 2022);

- the emergence of cyber threats and artificial intelligence along with new technologies such as hypersonic delivery systems, not least in Russia, where some are clearly covered by New START and others may not be (see INT: Hypersonic missiles lack arms control curbs - December 13, 2021);

- the proliferation of nuclear-capable short- and intermediate-range missiles, some of them covered by the now defunct INF treaty and all now at the centre of attention in light of Putin's threats (see RUSSIA: Tactical nuclear arsenal makes for high risk - October 27, 2022).

Beyond unilateralism

Congressional support gives the White House a rare bipartisan foundation for advancing the initiative both at home and potentially with other nuclear states.

The fail-safe review is expected to look beyond unilateral US action and consider both bilateral (with Russia and with China) and multilateral risk reduction measures. Even though current geopolitical conditions are not conducive, all nuclear-armed states have a vital interest in the fail-safe mechanisms of peers and especially adversaries.