Change to the EU's asylum regime will be slow

The EU states are deeply split about the distribution of asylum responsibilities

Updated: Aug 31, 2015

EU asylum-seeker distribution will remain contentious · All Updates

European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker on April 29 called the results of the EU's April 23 summit to address the Mediterranean boat people crisis "inadequate". Rising migrant flows across the Mediterranean are straining the EU's current 'Dublin' asylum system. Nearly all member states and EU institutions recognise the failures of the system, but no credible alternative has so far been proposed. The latest crisis appears to have prompted Germany to abandon hopes of securing improved implementation of the Dublin system, and to switch to calling for its replacement.

What next

Change to the EU's asylum system, in the direction of greater burden-sharing, will be slow and contentious. Unless the EU states tackle their disagreements about asylum responsibilities, it will be difficult to achieve progress in other areas aimed at addressing the Mediterranean crisis.

Subsidiary Impacts

- The EU's Frontex missions in the Mediterranean are unlikely to take on a search-and-rescue mandate.

- This will leave commercial shipping to continue to take much of the burden of dealing with migrants in distress.

- Deaths of migrants in the Mediterranean and elsewhere are unlikely to decline as smugglers adapt their practices to EU enforcement measures.

Analysis

The EU has been working on a Common European Asylum System (CEAS) since 2009. The bloc's current asylum regime consists of a complex mix of EU-level and national-level law, policies, standards and practices.

Several EU directives set common standards for the evaluation and processing of protection claims, and for the treatment of applicants while this is taking place. However, member states are responsible for transposing these standards into national laws and practices. Asylum claims are lodged with a member state, not the EU; and member states are responsible for integrating accepted refugees or returning failed applicants.

Member states retain most relevant responsibilities in the asylum field

Border control also remains a national responsibility. The EU agency Frontex is an instrument only for coordinating between member states, and bringing additional capabilities to assist others if necessary, including though joint border control missions.

While asylum and border control remains largely a national responsibility, 22 EU states (and four others) have created the common Schengen area of unrestricted travel. As long as this dichotomy exists, the EU faces issues arising from the secondary intra-EU movement of non-EU migrants.

'Dublin system' controversies

Of the policies comprising the CEAS, the 'Dublin' and 'Eurodac' Regulations are the most controversial. The 'Dublin system' is intended to ensure that any asylum-seeker lodges only one application within the bloc, which is handled by only one member state.

The Dublin and Eurodac Regulations set out procedures and criteria for determining which member state is responsible for handling any one asylum claim. The Dublin Regulation stipulates that asylum applicants who arrive in EU territory irregularly -- and do not have connections in another member state -- should claim asylum in the first member state they enter.

To enforce this, the Eurodac Regulation requires member states to record the fingerprints of irregular migrants and asylum applicants in a central database. An intra-bloc system of 'Dublin transfers' is intended to allow member states to return an asylum applicant to the state deemed responsible for handling his or her claim.

Asylum claim disparities

EU states are arguing about 'fair' distribution of responsibilities within the asylum system

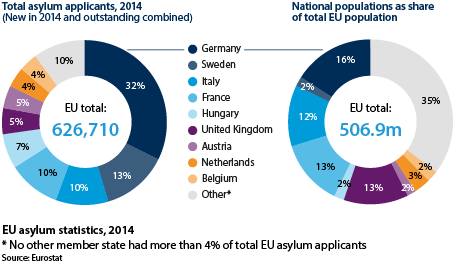

Although EU border states receive most irregular arrivals, asylum-seekers generally file their claims in other member states. For example, Italy saw over 170,000 boat arrivals in 2014, but registered only 65,000 new asylum applications. Available evidence suggests that the strongest factors determining where asylum-seekers claim protection are related to integration prospects. However, member state policies also play a role. For example, Sweden has received a large share of asylum applications from Syrians after announcing it would grant all Syrian applicants permanent residency.

The disparities between member states in the numbers of irregular arrivals and asylum applications give rise to significant tensions (see NORTH AFRICA: Migration adds to EU's north-south split - December 11, 2013). Authorities in Germany have accused Italy of intentionally neglecting to fingerprint irregular arrivals. For its part, Italy has complained that the Dublin rules leave it with an unfair share of responsibility.

Mediterranean mission disputes

These disputes spill over into arguments about border control in the Mediterranean. Italy has pressed for an EU maritime mission with a search and rescue mandate, to replace its Mare Nostrum operation which ended in late 2014. Frontex's Triton mission, which launched as Mare Nostrum, has only a border control mandate (and thus operates only in EU waters) (see LIBYA: Halting migrant flows to Europe will take years - April 20, 2015). Some member states have refused to support an expansion of the mandate without guarantees from Italy of compliance with Dublin and Eurodac, including fingerprinting.

European Council plans

At the April 23 European Council meeting, EU leaders identified four priorities for addressing the Mediterranean migrant crisis, namely:

- fighting people trafficking, primarily by targeting smugglers;

- preventing illegal migration, through increased cooperation with African source and transit countries;

- reinforcing the CEAS, partly by deploying more assistance to frontline states for asylum-processing, including registration and finger-printing; and

- increasing the funding and assets of Frontex's Triton operation, and the parallel operation 'Poseidon' off Greece.

While the Council's conclusions referred to an "increase [of] the search and rescue possibilities" of Triton and Poseidon, they reaffirmed Frontex's mandate, which remains limited to EU waters. There is thus no like-for-like replacement of Mare Nostrum.

The provision of more asylum processing assistance to Italy is likely to bring some immediate improvement, but the measure does not address reception capacity -- a major issue for Rome.

The EU's plans suffer from two underlying weaknesses:

- They do not address adequately the ultimate drivers in Africa of the trans-Mediterranean traffic (see AFRICA: Migration will exacerbate skill shortages - April 30, 2015).

- EU leaders failed to make progress on the disagreements between member states on asylum responsibilities.

They agreed to "consider options for emergency relocation [of asylum-seekers] between all member states", as well as to establish a pilot project on pan-EU refugee resettlement. However, both schemes would be voluntary. The Council conclusions made no mention of reassessing the Dublin system.

EU policy outlook

The EU states are now split between those supporting and those opposing non-voluntary relocation plans.

Germany had previously focused on securing the full implementation of the Dublin system. However, at the April 23 summit, it became clear that Chancellor Angela Merkel now advocates the replacement of Dublin. This shift aligns Germany with some EU border states, such as Italy, but places it at odds with the United Kingdom, which opposes any non-voluntary relocation plans (at least under its current government, ahead of the May 7 election).

In his remarks on April 29, Juncker said that the European Commission would on May 13 propose a relocation system. However, it is unclear whether this would be a compulsory scheme, or a worked-up version of the voluntary proposal indicated in the European Council conclusions.

Juncker also suggested that the EU needed to "leave the door partly ajar" to legal migration, or risk fuelling illegal migration flows. Several member state policymakers, including Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi and German Interior Minister Thomas de Maiziere, have proposed establishing centres outside Europe for refugees to submit asylum claims. However, both EU external processing and refugee resettlement would face the same disagreements over burden-sharing as have plagued the regular asylum system.

_350.jpg)