Prospects for Syria and Iraq in 2016

Intensified international efforts to fight Islamic State group and end the Syrian civil war will yield limited results

Russia's direct military intervention in Syria and terrorist attacks by the Islamic State group (ISG) against Russian and French targets have sparked unprecedented diplomatic activity around the Syrian conflict, suggesting that a political solution could see the light in 2016. In Iraq, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi's leadership faces a 'make-or-break' year as he seeks to handle the campaign against ISG, an economic crisis, and a political backlash against his reform programme.

What next

Persistent strategic divergences between the main external parties involved in the Syria conflict are likely to result in a diplomatic stalemate. The conflict is also likely to remain deadlocked on the ground, although some localised breakthroughs are possible. In Iraq the campaign against ISG will make slow but steady progress. The prime minister should succeed in pushing through a watered-down version of his reform programme, but he will face further challenges over the status of the popular militias.

Strategic summary

- The dynamics of the Syrian conflict will not see dramatic structural changes throughout 2016.

- Intensified international air strikes are likely to increase refugee flows from Syria.

- Strong southern oil exports and IMF assistance will help the Iraqi government contain the economic crisis.

Analysis

The diplomatic consensus over the need for a broad alliance against ISG will be undermined by conflicting strategic priorities of the main external powers.

Syria

Although the destruction of a Russian airliner over the Sinai has made ISG a more pressing concern for Moscow, the latter's priority in Syria remains the defence of President Bashar al-Assad's regime.

Transition talks

Russia does not believe that any alternative leadership could preserve its strategic interests in Syria, and will therefore push for a political solution that only involves a superficial overhaul of the current regime.

The United States will reject Russian and Iranian efforts to push through a cosmetic transition since this would grant Russia and Iran total victory in Syria, and would damage Washington's relations with its allies in the Gulf and Turkey.

France's possible embrace of a more accommodating stance towards Assad in the run-up to the 2017 presidential election will be hampered by Washington's more cautious position.

Military stalemate

Russian air support is unlikely to tip the balance drastically in the regime's favour, given the latter's lack of manpower.

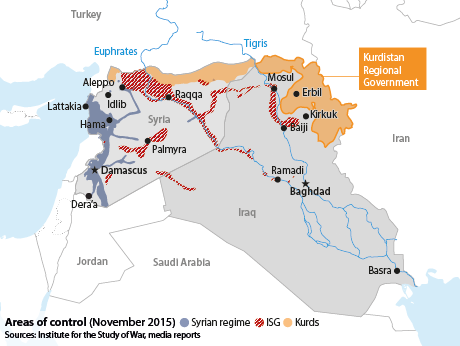

Ground offensives supported by growing numbers of Iranian Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC) members and Iraqi Shia militiamen will focus on expanding the buffer areas around the regime's key communication lines and urban centres (Damascus, Homs, Aleppo and Lattakia) rather than on retaking sizeable swathes of territory from the rebels.

Regime ground offensives will focus on securing core areas rather than retaking territory

While this could degrade rebel logistics and deal them symbolic blows, it will not defeat them. They will remain in control of territorial strongholds from which they will attack the regime's weak points. The Russian intervention will encourage al-Qaida affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra to close ranks with mainstream rebel groups and maintain a relatively pragmatic line.

Front lines could shift more significantly, though indecisively, in the sparsely populated central steppe, where loyalist forces will try to seize back Palmyra from ISG and reopen the road to their besieged garrison in Deir ez-Zor.

Anti-ISG campaign

The most striking change in the conflict over the next year might occur along the Turkish border. Turkey seems keen to help its rebel allies to seize the last segment of the border under ISG's control (Jerabulus). By protecting the rebels' eastern flank in Aleppo, this move will help the rebels withstand regime offensives in the region (see SYRIA: Turkish zone will push back 'Islamic State' - August 11, 2015).

The closure of the Turkish border will also facilitate the southward offensives waged by the Kurdish-Arab Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) against ISG possessions in the Euphrates and Khabur valleys. However, Kurdish domination over the SDF and the weakness of their Arab component will hamper progress towards ISG's core Syrian stronghold, the Raqqa-Deir ez-Zor axis.

Russian intervention

Russia will expand its substantial military presence, deploying further aircraft and advanced anti-aircraft systems such as the S-400. However, Moscow will hold back from a major ground intervention unless it is part of a broader international force.

Russia's targeting of logistical and medical facilities in rebel areas, and US targeting of oil production in ISG-areas will cause living conditions to deteriorate significantly, triggering greater refugee flows (see SYRIA: Aid boost will not reduce refugee flows to EU - September 22, 2015).

Russian military pressure and the Western countries' lack of resolve towards Assad will also strengthen the cohesion of the alliance between Saudi Arabia, Qatar and mainstream rebel groups.

Iraq

Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi faces a tough political battle to save his ambitious flagship reform programme amid mounting opposition to the scale of planned cutbacks to government (see IRAQ: Abadi likely to survive reform challenge - November 12, 2015).

If the reforms fail, Abadi's authority will be weakened for the rest of his premiership, and his hardline opponents, including Nuri al-Maliki and politicians aligned to the Shia militias, will be empowered. Abadi's weakening would also reduce the prospects of an inclusive national government that can operate effectively across the sectarian divide.

Abadi may seek a compromise on the most contentious issue, public sector salaries, but will also need to address the thorny question of the integration of the popular militias into the armed forces.

Whatever the outcome of his reforms, Abadi is likely to remain in office until the end of his premiership in 2018, given US and Iranian support for keeping him in place.

Economy and oil

The reform programme is also a key part of the government's response to the economic crisis brought about by the twin fiscal shocks of a drop in oil prices and increased military costs of the war against ISG.

Low oil prices are putting pressure on government revenue, with the budget deficit set to reach 12% of GDP next year and foreign exchange reserves dipping to 59 billion dollars, or nine months of goods and services imports, according to the IMF.

12% of GDP

Projected budget deficit in 2016

The government has good economic policies in place to deal with the crisis, if it can overcome the political obstacles, while IMF support should help tide the government over the coming year.

Baghdad will hope that renegotiated contracts with international oil companies operating the southern oilfields will mean a reduction in the volumes of oil it hands over to them as payment, in line with low global oil prices. The companies have also been asked to trim their budgets for 2016 because of Iraq's fiscal constraints, slowing down production expansion programmes.

Southern oil exports are likely to continue at around 3 million barrels per day.

Kurdish tensions

Relations between Irbil and Baghdad are unlikely to improve in 2016. Baghdad's northern exports will remain suspended given limited prospects in 2016 for a deal with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) over sharing receipts from oil pumped through Turkey (see IRAQ: Kurds are on course for economic independence - August 4, 2015).

Exports from the Kurdish region will continue at around 600,000 barrels per day, but the low energy prices will mean that international oil companies there will face further delays in receiving their share of production.

However, Kurdish factions are likely to contain their own dispute. The coalition government comprising the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Gorran should hold until the 2017 elections despite tensions over the extension of President Masoud Barzani's presidency and the KDP's dominance of Kurdish institutions.

Security

The military campaign against ISG will make slow but steady progress over the next year.

The recent defeats of ISG in Sinjar and Baiji, and advances around Ramadi signal that the momentum against the group is gathering pace. Kurdish forces in Iraq and Syria are launching a two-pronged offensive to cut off the main supply route between the group's main cities of Raqqa (Syria) and Mosul (Iraq).

Federal forces could launch a Mosul offensive towards the end of 2016

Iraqi forces could be in a position to launch an assault on Mosul in the latter half of 2016. However, much will depend on internal Iraqi dynamics, with political rivalries between federal forces and the Shia militias, and sectarian sensitivities between Kurds and Arabs likely to slow the pace of operations.

A key challenge will be resettlement and reconstruction in areas retaken from ISG. Given the level of destruction and heightened sectarian tensions, progress on this front may also be slow and localised sectarian conflicts could erupt.

Increased ISG-linked terrorist activity abroad will bolster Western support for the Abadi government and its fight against the group. Iraqi politicians will show support for bringing Russia on board to the military campaign, but this should be viewed more as a rhetorical device to pressure the West to step up its own support to Baghdad, rather than any serious attempt to challenge the United States's role as Iraq's key external backer alongside Iran.

_350.jpg)