Temer will face vast political challenges in Brazil

Unpopularity, recession and the difficulties of building a stable coalition mar the acting president's prospects

Michel Temer became acting president on May 12, after the Senate voted 55-22 to accept impeachment proceedings against Dilma Rousseff. The easy win of the pro-impeachment camp suggests Rousseff will be removed permanently after her judgment, which now senators must finish in no more than 180 days. However, this will not translate into solid parliamentary support for the Temer government. While the acting president is a seasoned political operator, he has started his government with low popularity and a democratic deficit in the eyes of large sectors of society, and his 'honeymoon' period with Congress will be short in the best-case scenario.

What next

Temer was catapulted to power by a broad coalition of social, economic and political actors held together by their opposition to Rousseff, but with often conflicting interests and agendas. Now the savage recession and the anti-corruption anger that were at the basis of widespread dissatisfaction with the suspended president can quickly turn against the new government. Together with an array of political challenges, this will limit its ability to deliver the economically orthodox changes Temer has pledged to seek.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Financial markets may be over-optimistic regarding Temer's ability to reform the economy.

- Uncertainty over who will be speaker of the Lower House could delay key votes.

- Lack of diversity in his all-male cabinet will create unnecessary controversy for Temer.

Analysis

Temer's track record and political profile suggest he will be much more adept in his dealings with Congress than Rousseff. The suspended president had never held elected office before winning the 2010 vote and was widely criticised for not holding dialogue with congressional leaders. The interim president, by contrast, was elected federal deputy in every election between 1986 and 2006 and served three times as speaker of the Lower House.

Fragile coalition

In recent weeks, as it became clear that he would inherit the top job, Temer initially signalled that he would slash the number of ministries and have a cabinet of 'notables', selected by their expertise rather by political calculations.

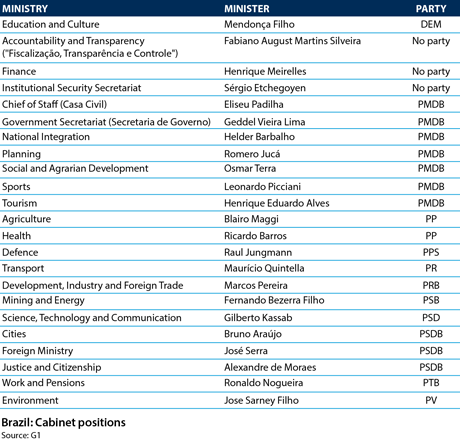

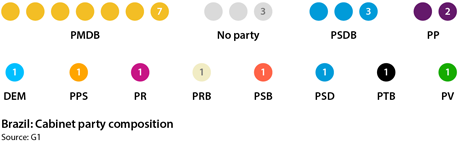

It was a nod to popular anger against one of the most infamous features of Brazilian politics, the trading of cabinet and other government positions for support in Congress -- a strategy that leads to large but heterogeneous and unreliable coalitions (see BRAZIL: Governance will become more challenging - September 17, 2015). In the end, he:

- announced a cabinet with 23 ministries, down from 32 under Rousseff; but

- bowed to the 'iron law' of coalition-building horse-trading.

While the latter is essential for any Brazilian government in the absence of a comprehensive political reform, Rousseff's demise has shown how fragile the support of interest-driven coalitions can be. Keeping allies happy with fewer ministries and the announced elimination of 4,000 federal government jobs by the end of 2016 will be an arduous task.

Temer slashed the number of ministries, but bowed to horse-trading politics

The typical move for parties eyeing the presidency would be to leave the government's coalition if they sense this is becoming weaker around one year ahead of the polls, due in October 2018 -- as the centrist Socialist Party (PSB) did when it left Rousseff's government in 2013 (see BRAZIL: Silva changes presidential race's dynamics - October 11, 2013).

The hesitation of the centre-right Social Democratic Party (PSDB), which came second in all presidential elections between 2002 and 2014, to join Temer's government officially suggests the new executive's underpinnings are already far from solid.

Intra-party disunity

If maintaining the loyalty of the eleven parties with cabinet positions will be a challenge, disunity within the two main parties in the cabinet -- Temer's own Democratic Movement Party (PMDB) and the PSDB -- could prove no less problematic (see BRAZIL: Parties battle to respond to political crisis - January 4, 2016). Historically, effective presidents have tight control over their own parties and maintain their allies' interests aligned with their own. This is unlikely to be the case now.

PMDB

The PMDB is a catch-all party with no unifying ideology. While Temer served as its president between 2001 and April 2016, the influence of any leader is limited by the fact that the party is a coalition of regional interests. For example, some of its ministers were reluctant to leave Rousseff's cabinet after the party ordered them to do so in the run-up to the Congress votes on the impeachment proceedings against her.

Being traditionally the largest party in Congress thanks to the support its local leaders enjoy, the PMDB has long placed itself at the core of Brazil's horse-trading politics. Now Temer will be on the receiving end.

PSDB

The PSDB supports Temer's economically orthodox agenda (see BRAZIL: Temer would seek orthodox policy turn - April 18, 2016), whose implementation will in part depend on the party's votes in Congress. However, the PSDB is a deeply divided party:

- It has three viable and ambitious potential presidential candidates, including new Foreign Minister Jose Serra, and has seen significant infighting recently.

- Party fragmentation, a distant prospect until recently, now seems a possible scenario.

In this context, support for the government is likely to be dictated more by the calculation of each of the party's leading groups than by a coherent strategy.

Beyond party politics

Roadblocks and other protest initiatives by social movements that oppose Rousseff's impeachment and abhor Temer's agenda -- such as the Homeless Workers' Movement, the Landless Rural Workers' Movement and the National Students' Union -- are set to be a feature of the new political scenario.

Meanwhile, the support of social actors that united against Rousseff will be wobbly. For example:

- Union Force, a pro-impeachment labour group, was quick to criticise proposals to reform the pensions system backed by the new finance minister, Henrique Meirelles.

- The Federation of Industries of the State of Sao Paulo, Brazil's leading business lobby, rejected the possibility, also mooted by Meirelles, that the financial transactions tax (CPMF) could be temporarily recreated.

Several new ministers face pending legal cases

The new government could also face renewed major anti-corruption street protests. Temer himself was recently condemned by the Sao Paulo Regional Electoral Court in a case related to illegal campaign funding practices. Furthermore, several of his new ministers face pending legal cases or corruption-related investigations.

Unpopularity

Perceptions that old practices persist although some names may have changed could fuel discontent; pot-banging protests in several cities accompanied a Temer television interview yesterday. This discontent may rise further given that Temer has already started his government as an unpopular president:

- A Datafolha survey in April showed that 58% supported his impeachment (against 61% who backed Rousseff's).

- This is against a background of deep recession and possible growing dissatisfaction given that many of the new government's measures will be unpopular -- some could even further depress the economy before supporting long-term growth.

This context means Temer will have a narrow window of opportunity to pass the reforms he has pledged to seek. The acting president will hope that his initial efforts to address the fiscal deficit and improve the business climate will swiftly create confidence and lead to an increase in private investment, contributing to an unlikely recovery in the short term (see BRAZIL: Post-impeachment prospects would remain muted - April 25, 2016).

_350.jpg)