Syrian government forces may retake Damascus suburbs

Aleppo is set for a prolonged siege, but President Bashar al-Assad has the advantage near the capital

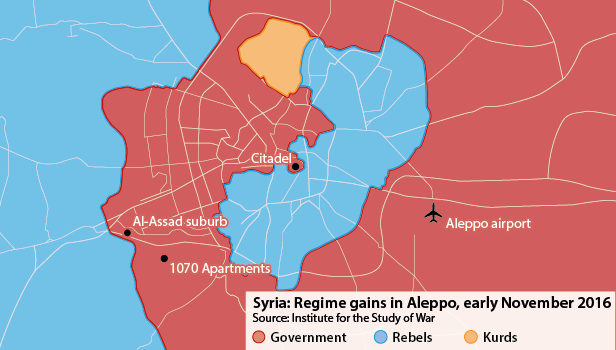

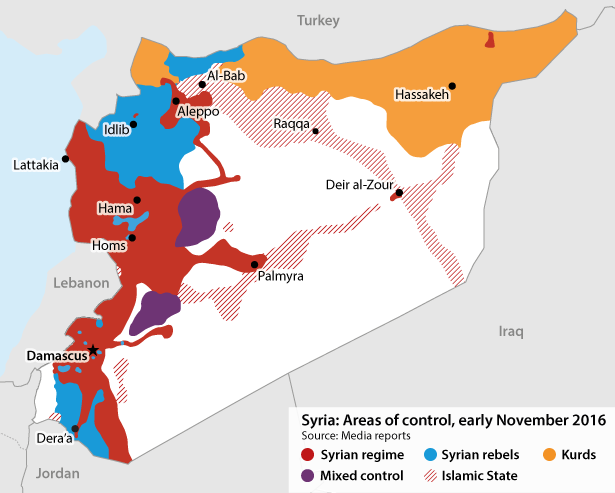

Government forces resumed bombing rebel-held eastern Aleppo on November 15 as Russian planes launched new strikes across the Syrian countryside. Forces loyal to President Bashar al-Assad on November 9 recaptured the 1070 Apartments district on the western outskirts of Aleppo, marking the failure of the rebels’ second push to break the siege imposed last July. Government forces are also advancing elsewhere, notably in Damascus.

What next

The rebellion is likely to become a rural insurgency, retaining sufficient strategic depth to pursue its war of attrition against loyalist forces but unable to threaten the government's existence in the medium term. The siege of Aleppo is set to continue as a brutal war of attrition. More dramatic change might come in the eastern suburbs of Damascus, where Assad’s best units are poised to take advantage of more favourable terrain consisting of cultivated land and small towns.

Subsidiary Impacts

- Assad's forces will try to attack a weakened Islamic State (IS), but will be unable to divert significant military resources.

- Hard-line Islamists are likely to benefit from a diminution of US support to moderate rebels under the Trump administration.

- A Turkish-led rebel offensive on al-Bab would bring forces dangerously close both to loyalist units and to rival Kurdish rebels.

Analysis

Russian air support and a several-thousand-strong Iranian-led Shia contingent allowed the Syrian army in July 2016 to complete a three-year campaign aimed at encircling rebel-held areas of Aleppo from the south-east (see SYRIA: Rebel defeat in Aleppo will boost al-Qaida - July 22, 2016).

In August, rebels in Jaysh al-Fateh, an alliance dominated by the salafi-jihadist Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (JFS) and salafi Ahrar al-Sham groups, attacked from their stronghold in Idlib. They established a narrow land connection with Fateh Halab, a moderate Islamist coalition that forms the bulk of the opposition's fighting force in eastern Aleppo. However, pro-Assad forces counter-attacked the following month and restored the siege.

Despite initial success, including the capture of the Al-Assad suburb to the west of the city, a second Jaysh al-Fateh offensive launched in late October rapidly stalled and then suffered significant setbacks during its second week.

Around Aleppo

Further attempts to break the siege of Aleppo from the countryside will remain a significant threat to the government. Insurgents control rural Aleppo and Idlib, and continue to receive arms from Turkey. However, they are unlikely to succeed, given Russian and Iranian military support for Assad.

The siege of Aleppo is set to continue

The considerable casualties suffered by the insurgents might instead convince them to opt for small-scale attacks aimed at pinning down loyalist forces in the western suburbs. Jaysh al-Fateh will also retain the option of pressuring Assad's forces through sporadic attacks against the western suburbs' sole supply line, the Hama-Athriya-Khanasir desert bypass.

For their part, pro-Assad forces may be averse to suffering major casualties to capture a large urban area defended by thousands of battle-hardened insurgents. Aleppo is therefore likely to experience a continuing siege, with destructive air and artillery attacks against rebel-held neighbourhoods and a war of attrition on the western and southern front lines. Assad will hope that lack of supplies and internal divisions would push the rebels towards surrender.

Northern provinces

Northern rebel forces lost access to Aleppo in February 2016, when the Syrian government and Kurdish Syrian rebels simultaneously attacked their positions, with Russian air support. However, their participation in the Turkish-led Euphrates Shield offensive against IS, launched in August, has enabled them to reconstitute some strategic depth along the border (see SYRIA: Turkey involvement will deepen conflict - September 9, 2016).

The Euphrates Shield offensive is now close to al-Bab, a sizeable population centre located near government positions in the eastern Aleppo countryside. Turkey is certainly keen to avoid any direct confrontation between its Syrian clients and Assad's forces, but if al-Bab is taken, the former will effectively be in a position to threaten the latter's eastern flank, raising the risk of miscalculation and escalation.

Further south, the rebels temporarily succeeded in diverting loyalist energies from Aleppo by launching an initially successful offensive on the northern countryside of Hama in late August. In October, however, pro-Assad forces exploited infighting between mainstream rebels and the salafi-jihadist Jund al-Aqsa faction to regain lost ground. They also reversed tentative rebel progress in the neighbouring province of Lattakia.

Although the net result of the interconnected military developments in the northern provinces of Aleppo, Hama and Lattakia has been negative for the insurgency, its survival in these areas is not currently in doubt.

Damascus suburbs

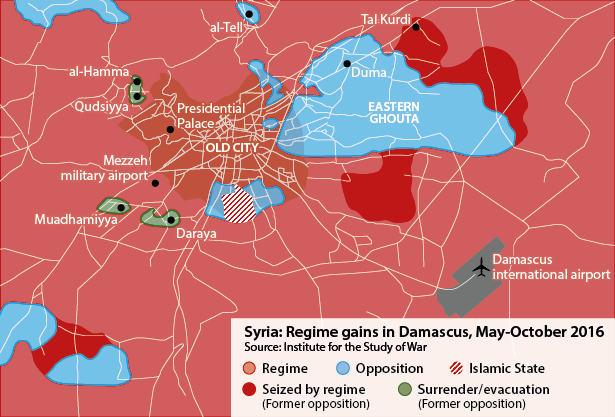

In Damascus, on the contrary, the rebels are facing a looming threat of extinction. They have lost significant ground in the eastern suburbs, their main stronghold, and evacuated most of the western and northern peripheries.

Evacuations could push rebels out of Damascus suburbs

Moscow's September 2015 intervention in Syria convinced Jordan to curtail arms supplies to the Southern Front, the leading non-Islamist rebel coalition in the southern provinces of Dera'a and Qunaytra. Meanwhile, civilian leaders in the southern provinces began to negotiate local truces with the government. This enabled the Assad government to relocate military resources from the south to Damascus.

After it became clear in 2014 that loyalist forces were unable to reconquer rebel-held suburbs of Damascus, a system of local truces emerged, as part of a process of reconciliation ('musalaha'). Insurgents could remain in their positions and keep their weapons, but stopped fighting pro-government forces in exchange for vital supplies.

Assad's new position of strength, however, has allowed new patterns to emerge. Instead of 'musalaha', government officials now offer only 'musamaha' (pardon).

In August 2016, in the south-western suburb of Daraya, rebels on the verge of defeat were offered not a truce but the evacuation of the area for all fighters to the rebel-held province of Idlib, where the government believes it can contain the insurgent threat through bombing attacks. Thousands of civilians were also removed from their homes to other parts of Damascus.

Subsequently, long-standing truces were simply abrogated in Muadhamiyya, Qudsiyya and al-Hamma, where the rebels were similarly forced to leave for Idlib along with their families. This has freed up manpower for government units to make further inroads into Eastern Ghouta, the last major insurgent stronghold near Damascus.

In late October, loyalist forces took control of the strategic town of Tal Kurdi, to the north-east of Damascus. From there, Assad's troops aim to capture Duma, the capital of Eastern Ghouta -- or, alternatively, exert sufficient military pressure to shape ongoing discussion of a truce to their advantage.

US strategy

Assad and his allies hope that their recent victories will force Western and regional players to abandon the opposition and, eventually, reconcile with Damascus. The US presidential election of Donald Trump, who has expressed a willingness to cooperate with Russia on Syrian issues, has strengthened these hopes.

If they are justified, this would mark a major divergence with Washington's longstanding regional allies, who are reluctant to change their stance on Syria. Both Israel and Saudi Arabia would see Assad's resurgence as an unacceptable Iranian victory -- and Trump himself has also spoken against Iranian influence.

How the president-elect tries to square this circle will be a key factor in the future of the Syrian conflict.

_350.jpg)